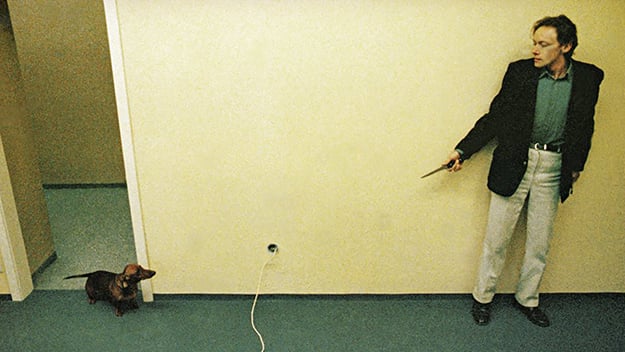

Angst (Gerald Kargl, 1983) At this year’s Viennale, the largest film festival in Austria, a strong and idiosyncratic selection of recent festival premieres coexisted with multiple retrospective series, dense with rarities, that stole the spotlight. At center stage was a massive, 41-film program dedicated to the Chilean master Raúl Ruiz. Works by Valeria Sarmiento, Ruiz’s widow and frequent collaborator, could be found in the Ruiz program as well as in a separate, comparably robust series on Chilean cinema since the 1973 coup d’état. Another section covered the globe-trotting films of collaborators Nicolas Klotz and Élisabeth Perceval, which are little known outside of France; still another offered shorts by the Argentine experimentalist Narcisa Hirsch. Among these cinematic riches (and yes, there are even more), a roundup of local offerings—Austrian films from the ’80s—stood out, in part because its centerpiece title, Gerald Kargl’s serial-killer curio Angst (1983), is a pet fascination of mine. Beloved by provocateurs like Gaspar Noé (who included Angst on his 2022 “greatest of all time” list for Sight and Sound), the film holds cult-classic standing today for its uninhibited violence. Its dizzying first-person immersion into the mind of a killer is markedly distinct from the approaches of the genre’s classics, which tend to attach neat psychological motivations to their mastermind murderers (Hannibal Lecter, the Zodiac killer, etc.) and Freudian nutcases (Peeping Tom’s Mark Lewis, Norman Bates). Angst mocks these attempts at meaning-making from the get-go: the psychopath K (Erwin Leder) explains the roots of his sadistic proclivities and his fraught family origins in voiceover throughout the film, but his steady meditations are merely impotent rationalization for such a profound will to destruction. The flimsy legal system, which deemed this psycho fit for release, is no match for his bloodlust: as K confesses, he simply lied during his psychiatric evaluation sessions. The film tracks roughly 24 hours in K’s life, starting as he’s freed from prison and immediately begins the hunt, prowling the streets like a starved animal. The film is disturbingly loyal to the real-life crime spree it draws inspiration from: the case of then-paroled killer Werner Kniesek, who in 1980 inspected various Austrian villages, eventually invading a villa where he terrorized and murdered a young girl, her mother, and her disabled brother. Using a SnorriCam—which utilizes a device that rigs the camera to the actor’s torso and captures the actor’s face directly—Kargl homes in on K’s delight and the perversely erotic nature of his physicality. (I always remember how in one scene, mid-torture, he pauses to take large drink of water.) Angst’s notoriety was enhanced by its censorship across Europe—the Viennale’s premiere of the new restoration is the film’s first public screening in Austria since 1983. Made on a 400,000-euro budget, and financed largely by Kargl himself (who never made another fiction feature but went on to a rather lucrative career directing commercials and educational films), the film was a financial disaster and a total oddity within the Austrian moviemaking landscape. Suffice it to say that genre films—especially sleazy murder movies that poked (hard!) at the bourgeois establishment’s worst fears—were not typically being made in Austria at the time. The ’80s were a period of transition for the country’s film industry. In 1981, the Austrian Film Fund was established, which subsidized national filmmaking and revamped the country’s commercial output. After World War II, Austrian popular film consisted largely of anodyne comedies and historical epics that capitalized on nationalistic nostalgia (such as the Sissi movies, a series of lavish monarchy-era period pieces starring a teenage Romy Schneider). Experimentation flourished in the ’70s through the efforts of independent filmmakers and visual artists like Peter Kubelka, Valie Export, and Kurt Kren, but the Film Fund allowed for the overhauling of mainstream films by Filmakademie-trained “professionals” and newly established production companies. Thus emerged a wave of mid-budget thrillers, fantasies, and social dramas forged by a modern and deeply conflicted sense of cultural identity. The ’80s program (curated by the Austrian Film Archive and extending past the Viennale, through the end of November) is winkingly named Keine Angst! (or “No Fear!”). It spotlights the beginnings of the so-called New Austrian Cinema—the “feel-bad” films of Michael Haneke and Ulrich Seidl. We feel the decade’s sharpened sense of urban and political malaise in the grim nightscapes of Dieter Berner’s Ich Oder Du (Me or You, 1984), a sordid melodrama that revolves around a ménage à trois of twentysomethings caught up in drugs, rock ’n’ roll, and psychosexual torture. The film pits a woman’s two unstable suitors against each other in a grimy Viennese underworld akin to the crime-riddled purgatories of similarly gutter-dwelling New York City– and London-set films of the era, like Ms .45 (1981) and Mona Lisa (1986). Die Nachtmeerfahrt (Sea Journey into the Night, 1985), by Kitty Kino, envisions a disorienting, nocturnal drift through Vienna’s shady nightlife scene in the mode of Variety (1983) or Simone Barbès or Virtue (1980), but with a playful, transgender twist—the protagonist is a female model who suddenly begins growing facial hair and taking on the bodily characteristics of a man, triggering an extended bar-crawl experienced from her newly gender-fluid point of view. After World War II, Austrian politicians clung to the narrative that the country had been a “victim” of Nazi Germany when roughly a third of the population were supporters of National Socialism and its anti-Semitic campaign. In 1986, Kurt Waldheim, a former United Nations secretary general, was elected Austria’s new president despite historical ties to the Nazi party; in 1988, Jörg Haider assumed leadership of the far-right Freedom Party on a platform that urged a return to the kind of ethnic and nationalistic pride that reigned throughout the war years. Two films in the program respond to horrific real-world developments like these—extensions of the country’s Lebenslüge, or the idea that Austrians have been living in self-denial about their relationship to the war since 1945—by illustrating fascism as a dangerous force of seduction. In Paulus Manker’s Schmutz (1986), co-written by a young Haneke, an obsessive security guard is relieved of his duties but nevertheless continues to watch over a decommissioned power plant. Drunk with the desire to continue his rule, the increasingly delusional man is manically beholden to his belief in so-called “property rights.” The violence he is willing to resort to on behalf of his broken principles reveals a profound spiritual devastation. Walter Bannert’s Die Erben (The Inheritors, 1983) isn’t subtle or symbolic about its critique of fascist indoctrination, and yet I found its approach, aligned with the traditions of horror, jarring and indelible. Composed of bluntly edited vignettes from the lives of two Austrian teenagers—one from a cold, bourgeois household; the other from an impoverished home filled with sexual violence—the film details their recruitment into a neo-Nazi youth organization. The “party” offers them a sense of community, a means of exorcizing their disgruntlement without veering into unearned empathy. (Bannert understands the appeal of fascism as a juvenile outlet for sexual frustration.) Die Erben envisions a world in which injustices are embedded into the very fabric of social life, forming tragedies whose perpetrators and victims can be one and the same. Beatrice Loayza is a writer and editor who contributes regularly to The New York Times, The Criterion Collection, Artforum, 4Columns, and other publications.