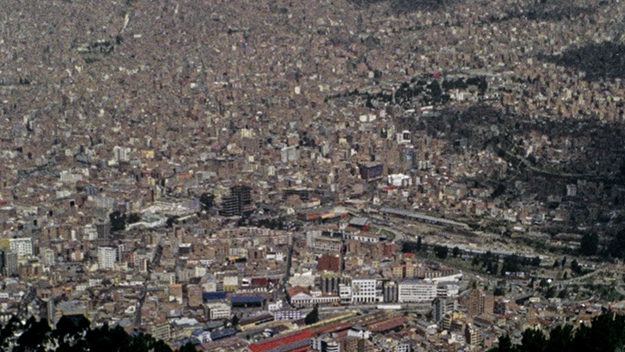

El gran movimiento (Kiro Russo, 2021) “I am a formalist,” Kiro Russo unapologetically declares in the press kit for El gran movimiento, his second feature and the middle of a proposed trilogy generated from his work in the Bolivian mining town of Huanuni. When he first arrived there in 2009, as he told an uncredited IFFR interviewer, Russo was drawn to the location less as a socially motivated chronicler and more from an interest in the aesthetic challenges of shooting underground: a mine, he noted, is “the darkest place in the world!” Maximalizing the director’s effects while revisiting shots and preoccupations from his earlier films (including shorts), Movimiento is grandiosely impressive from its opening, a six-minute series of slow zooms into and pans across La Paz’s skylines, the giganticist impact of the images accentuated by Miguel Llanque’s unignorable and galvanizingly loud modernist score. After the title card, Movimiento locates a human focal point in Elder (Julio César Ticona), a ne’er-do-well introduced in Russo’s first feature, 2016’s Dark Skull. Shot in Huanuni with the miners’ union as an official co-production partner, that film follows feckless, near-perpetually-drunk Elder in the wake of his father’s death as he struggles to adjust to mining life. Elder’s commitment to being deeply out of it at all times is as infuriating to his companions as it is easy to theoretically reconsider as a form of resistance: if you can’t walk a straight line, you definitely can’t perform backbreaking labor. At Movimiento’s beginning, Elder and two friends have arrived in La Paz (Russo’s hometown) as part of a larger group marching to the capital for work. They find plenty of manual labor there, but Elder is slower and weaker than his companions, incapable of lifting large bags of onions or crates without significant help. A doctor finds nothing medically wrong with him; as Russo told journalist Ersi Danou, what Elder is experiencing is the indigenous concept of mancharisk’a, when the soul leaves the body. A literally crushing workload—in which the ability to lift incredibly heavy objects is the normative baseline and anything less is inexplicable weakness—will do that. But a work-centric synopsis of Movimiento distorts its primary qualities as much as its Super 16mm grain imposes swirling, disorienting patterns onto La Paz. Made in collaboration with blue-collar nonprofessionals, as is standard for Russo, Movimiento’s primary effect is not to create either anger or empathy over the working conditions of exploited indigents, but to overwhelm with a series of disorienting sights and sounds. The bravura opening is self-consciously in the vein of Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, approaching La Paz from a great distance—much as Walter Ruttmann entered his metropolis via its train tracks, accelerating the editorial tempo as he drew closer to the city center. Here, the first zoom approaches the city from a great distance, with subsequent pans—over building walls and distorting windows—coming from within. Like Ruttmann on rails, the cutting then accelerates with staccato close-ups of transit—in this case, La Paz’s almost-brand-new system of aerial cable cars jolting under wires. The vantage point from one of these vehicles (which can elevate up to 1,640 feet) creates a dazzling moving backdrop later in the film, while Elder and his companions are merely relocating from one place to another and discussing his inexplicable malady. Russo ruptures the focus on Elder by introducing a shaman character of sorts, Max (Max Bautista Uchasara)—first seen in the countryside, eventually making his heavy-smoker’s-cough way into the city. His eventual convergence with Elder provides Movimiento’s primary narrative trajectory, but the film is far from a neat twining of separate plotlines. The pre-credits sequence ends with a slow zoom toward a wall covered with fading posters pasted on top of each other, a bricolage of text and images that acts as a metaphor for the film’s heterogeneous assemblage of elements, with no meaningful demarcation between the real and fantastical: tableaux of market life give way to a full-on dream-sequence dance number that turns outdoor commercial space into a nighttime site for play rather than grim labor. Likewise, Max’s muttering progression through the daytime countryside is intercut with nighttime shots of a glowing white wolf he’s symbolically linked to. Russo’s consistent commitment to discombobulation makes this a festival film that, while familiar in some of its forms of rigor, comes with its own unique sense of rhythm and pacing. Movimiento is a distinctive leap past Dark Skull’s literally murkier stylings, whose sepulchral darkness and emphasis on simulating the unmediated lives of the dispossessed courted Pedro Costa comparisons. While similarly monumentalizing the overlooked figures at its narrative center, this sophomore breakthrough’s visual confidence and unabashed brio place Russo closer to fellow Universidad del Cine student Eduardo Williams (The Human Surge), restlessly generating big effects in dispossessed spaces. At a compact 85 minutes (with credits!), Movimiento is a compressed formalist broadside, auguring well for the trilogy’s conclusion. Vadim Rizov is director of editorial operations at Filmmaker Magazine.