Aloha Wanderwell and Captain Walter Wanderwell in Mozambique She was “the world’s most widely traveled girl” and a driving force behind groundbreaking travelogues, but you won’t find Aloha Wanderwell’s name in film histories. As orphan-film expert Dan Streible notes: “She’s not even mentioned in the Women Film Pioneers Project website of 200 silent-era filmmakers.” Yet Wanderwell’s best work is equal to that of other pioneering traveler-filmmakers such as Burton Holmes and Lyman Howe. And with any luck, an ambitious restoration and preservation project led by the Academy Film Archive will help introduce her work to a new audience. Born Idris Hall in 1906, Aloha was a 16-year-old convent student when she applied for a position on an expedition to circle the globe by automobile, led by Captain Walter Wanderwell. For a girl who dreamed of adventure growing up in British Columbia, it was a chance to change her life. Walter Wanderwell himself was a product of self-reinvention: originally Valerian Johannes Piecynski from Thorn, Poland, he adopted a new name and an incongruous military uniform when he left his berth on a steamship in Baltimore and began a walking tour of the United States. His tours and lectures evolved into motorcades intended to bring a message of unity to every nation on earth, starting with a trip from Mexico to Alaska. Walter Wanderwell wasn’t far removed from American barnstormers whose aerial demonstrations financed their way across the country. His lectures in favor of the League of Nations couldn’t come close to financing his planned expeditions. Movies might, especially the kind made by itinerant filmmakers. Many of the earliest filmmakers were in fact itinerants, making a living by traveling to towns, filming inhabitants and landmarks, and then screening them to their subjects (and maybe selling them to a distribution house back in New York City). Edwin S. Porter of The Great Train Robbery fame began his career in movies as an itinerant exhibitor and then filmmaker.

Aloha Wanderwell and Captain Wanderwell in Japan Wanderwell absorbed the methods and strategies of these filmmakers, who realized that their first job was to boost whatever town they were filming in. Politicians, dignitaries, firemen, police, and especially children were essential to include, as were potential donors and theater owners. Back in 1897, Edison’s James White also relied on sponsorship from steamship companies and railroads to help defray his travel costs when touring Japan and China with his cameras. Wanderwell tried to do the same, asking for discounts on travel and lodging. Henry Ford was happy enough to sell the expedition on Model Ts, but reluctant to provide any actual funds. In 1921, Wanderwell set off for Europe on a tramp steamer. He advertised in London for “A good-looking, brainy young woman who is as clever a journalist as her appearance is attractive,” warning that “she must forswear skirts—and incidentally marriage—for at least two years, and be prepared to ‘rough’ it in Asia and Africa.” Most important, she must “learn to work before and behind a movie camera.” Wanderwell saw motion pictures as a way not only to finance his expedition but also to document it for posterity. The Twenties was an age of exploration in film. Movies had progressed beyond the actualities of the Teens, with their shaky pans across tourist traps or rides on streetcars. Viewers wanted the exotic, the obscure, the dangerous. Daredevil filmmakers were ready to deliver. Robert Flaherty filmed in the Arctic and later the South Pacific. Merian C. Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack journeyed across the mountains of Iraq and Afghanistan, then visited the jungles of Burma and Thailand. Within a few years Dr. Martin Johnson and his wife Osa, Frank Bring ’Em Back Alive Buck, and James FitzPatrick with his Traveltalks offered a steady supply of travelogue shorts and features.

Aloha Wanderwell and Captain Wanderwell in Egypt It was in Paris in 1922 that Wanderwell met Idris Hall, who would soon adopt the name “Aloha.” Fluent in several languages, she persuaded Wanderwell to add her and a chaperone to the expedition. Six feet tall and with striking features, Aloha became the center of attention wherever they traveled. The films, at first just a means of raising money at local screenings, reflect her growing prominence. Early scenes filmed in Holland feature prosaic shots of fishing boats raising sail, onlookers in native attire, local kids posed on the Model Ts. In Rome, Aloha is at the center of the frame, astride a motorcycle by the Coliseum, interacting with dignitaries, beaming at the camera. In a circular for an appearance in Czechoslovakia, she’s mentioned right after Wanderwell. In Egypt and the Middle East, she’s surrounded by milling, grinning men who barely reach her shoulders. Aloha took charge of the “Unit 2” Model T, becoming the first woman to drive from Paris to Peking. In Russia, she was named an honorary colonel; in China, she fired a mortar. Thinking ahead to potential viewers back in the States, Wanderwell saw Aloha as a crucial element in the new narrative he was constructing about the journey. By the time the expedition had reached California in January 1925, Aloha was a star. She met with Hollywood royalty Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks while Pickford was filming Little Annie Rooney, then hunkered down in an editing room, shaping footage into what would become the Wanderwells’ best-known work: With Car and Camera Round the World. (Numbers vary widely, but one Variety item stated that 40,000 feet of film had been shot.) In April 1925, Aloha married Wanderwell, and by 1927 she had given birth to two children. That same year the couple went to Africa, supporting their “Cape to Cairo” trip through theater bookings: “Captain Wanderwell and Aloha Wanderwell stage a complete show, carrying their own stage and equipment for use when halls and theaters are not available.”

Aloha Wanderwell and Captain Wanderwell in Rome Like musicians today, the Wanderwells had a “merch” table where they sold postcards, described as a “mainstay” of their show by one journalist. Lou Goldberg, “national exploitation director” for Warner Brothers, said that the Wanderwells were experts in staging stunts like phony brawls “for box office value.” Two years later, the Wanderwells were in New York at the end of a five-year world tour. They parked their six cars at 125th Street and Fifth Avenue, where they attracted “unusual attention.” They also played vaudeville theaters and town halls. The Wanderwells took With Car and Camera Round the World on tour, narrating their adventures to viewers while the movie screened. They also cut and re-cut their footage to suit individual audiences. The version of With Car and Camera that exists today runs approximately one half-hour; unfortunately, no scripts of the presentations exist, as Aloha would speak extemporaneously. Much of the footage, from teeming jungles to desert wastelands, was strong enough not to need narration. Both Wanderwells contributed to camera angles and composition. (Both could also operate the camera, but preferred to remain within the frame.) Faced with well-known sites, they often fell back on familiar camera setups. But given the opportunity to shoot a religious ritual in front of a jungle temple, for example, they used the camera to frame both the dancers and their remarkable setting in a single shot. And when one of the Model Ts slid into a ditch, they bring the camera in close to document how to muscle the car over rocks they used to repair the road.

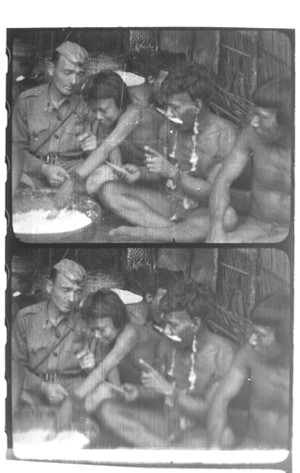

Wanderwell left an estate valued at $1,500, not much for a mother of two. Aloha had no choice but to continue writing and lecturing. Early in 1933 she released a 28-minute version of The River of Death through Ideal Pictures. A critic in Film Daily called it a “good adventure” with “excellent human interest sequences and some fair thrills.” Variety’s San Francisco stringer wasn’t as impressed, dismissing The River of Death as “anemic” and adding that Aloha’s appearance on stage—with her expedition cars, a monkey, and a “woman companion”—was “purely a good will measure.” Passing from travelogue to ethnography, The River of Death covers many of the same incidents found in movies like Trance and Dance in Bali, filmed by Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, and Floyd Crosby’s lost epic Matto Grosso: The Great Brazilian Wilderness. The Wanderwells’ footage includes Bororo natives building canoes, hunting, cooking, dancing, even becoming possessed by evil spirits and falling into frenzies. Aloha’s narration can sound insensitive to modern listeners, but she is careful to note how the villagers she filmed had fled into the interior to escape slavery on rubber plantations.

Aloha Wanderwell with her crew A year after Wanderwell’s murder, Aloha married Walter Baker in December 1933. By this point she was an accomplished filmmaker, especially compared to competition like Traveltalks. Her footage of the Taj Mahal and the Ganges River in 1936 is dazzling, as the Academy Film Archive’s meticulous restoration makes apparent. Aloha remains a key part of the frame, and now sports makeup and styled hair. But the camera angles she chooses are exemplary, giving viewers a sense of the scope and scale of the Taj Mahal’s architecture while offering unfamiliar vistas. A temple on the Ganges is filmed from a boat drifting languidly by, with Aloha and a companion gazing up at blindingly white towers. Aloha released To See the World by Car in 1937, followed by India Now and Explorers of the Purple Sage. But politics in the run-up to World War II had become a serious deterrent to filming. After writing a memoir, Call to Adventure!, in 1939, Aloha and her family settled in Ohio, where she worked in radio and print journalism. The Bakers moved to Newport Beach in 1947. Aloha’s last performance lecture was given at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles in 1982. She died in 1996. Why are her films so little known today? One reason is that they are scattered among several institutions. According to Heather Linville, a film preservationist at the Academy Film Archive (AFA): “Aloha donated 12 cans of nitrate print and negative rolls (excerpts, trims and outs) to the Academy (before the archive was established) in 1985. This was around the same time she was depositing selected film elements from her personal film collection to other film archives including the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and the Smithsonian Institution.”

So the Smithsonian has Last of the Bororos (30-31), a 31-minute, silent, B&W documentary, but the Library of Congress has The River of Death, its 28-minute, sound, tinted version. The Library also holds nitrate elements of some of Aloha’s films. Meanwhile, the Detroit Public Library has 10 boxes of Wanderwell papers—photographs, postcards, and negatives—in its National Automotive History Collection. The Nile Baker Estate donated the remainder of Aloha’s film collection to the AFA in 2014, most of it material shot from Aloha’s first trip around the world, used in With Car and Camera Around the World. A smattering of Aloha’s movies can be found on YouTube, but to fully appreciate her work, they need to be seen in a theater. The Academy restoration effort is impressive, involving new 35mm fine grains, duplicate negatives and print, as well as 2K scans from the newly produced fine grains. Linville has made frequent presentations of the AFA’s restorations—at an Academy-sponsored Orphan Films program in New York in 2014, and at the Women and the Silent Screen conference in Pittsburgh this past September. Richard Diamond, Aloha’s grandson, has assembled a comprehensive website about his grandmother. He has also reissued Aloha’s autobiography and will be donating her entire collection of photos, scripts, diaries, journals, scrapbooks, and text memorabilia to the AFA’s Margaret Herrick Library. Collectibles from Aloha’s travels around the world—including 280 auto badges, parts of the car she drove, leather film cases, and wardrobe—will go to the future Academy Museum. Aloha Wanderwell’s movies are filled with beautiful and startling images, captured before tourism became corporatized. The sight of their Model Ts racing down jungle roads, nosing around the pyramids of Egypt, or inching their way up a ramp onto China’s Great Wall, become richer and more mysterious for having been shot on 35mm nitrate. It’s time to recognize her extraordinary place in film history.