Chiseled into the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, D.C., above sculptures depicting a threadbare farmer couple and a stooped bread line during the Great Depression, is a quote from FDR’s second inaugural address, in January 1937: “I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished.” The quotation continues lower down: “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.” Playwright Arthur Arent excerpted the first line for the title of his 1938 stagework, vividly and accurately termed a Living Newspaper. The Living Newspaper was the name given to multimedia productions of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Theatre Project that sought to synthesize stage drama, one-act sketch, photography, and film in the service of New Deal–centered ideals. The Newspaper authors acted more like city editors than authors, dispatching armies of government-subsidized researchers to gather material (from the library and the streets) about a social issue du jour that would provide the architecture for the production. Triple-A Plowed Under, for example, dramatized the plight of Dust Bowl farmers, urging unionizing and the cutting out of commercial middlemen. Like many other FTP productions, Triple-A became a House Un-American Activities Committee target. So did the adaptation …One Third of a Nation…, which tackled the “ill-housed” portion of that FDR speech, in particular the abysmal state of middle- and low-income housing in New York City circa 1938. The original show, staged at the FTP’s own Adelphi Theatre, was something of a hit, its dazzling burning slum set seen by more than 217,000 in New York before the production successfully branched out to other cities. Broadway songsmith Harold Orlob purchased screen rights for a modest sum (which money bypassed Arent and went back into the FTP), and produced the film with director Dudley Murphy. The movie has Paramount’s name on it, but the studio only handled distribution—it is a genuine New York indie, shot on some city locations and the Eastern Service Studio in Queens. For Murphy, it’s another unique entry in a diversified portfolio that includes an experimental collaboration with Fernand Léger and Man Ray (Ballet Mécanique, 1924), and The Emperor Jones (1933), starring a groundbreakingly above-the-title Paul Robeson.

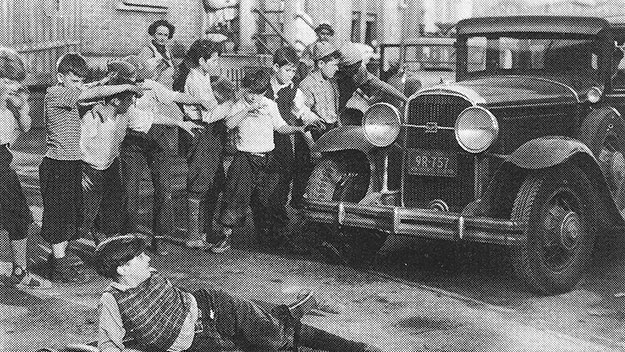

Murphy and screenwriter Oliver H.P. Garrett retain the source’s bedrock of anti-corruption outrage and anger at the cruel sins of capitalism that have made living conditions subhuman for so many, though they can’t resist leavening the material for cinematic audiences with a love story and happy ending. The film opens frantically, as a careless smoker starts a fire and local girl Mary Rogers (Bronx-born Sylvia Sidney) watches her young brother Joey (future director Sidney Lumet) tumble to the ground from the burning tenement house, cracking on a railing en route and crippling himself for life. Mary is horrified when she’s told the healthcare cost (“Expense? I thought it was free!”), but a symmetrical white knight named Peter Cortlant (Leif Erickson) foots the bill. A real estate scion, Cortlant is later startled to learn that he’s actually the ashen dump’s landlord, raising the ire of the still reluctantly smitten Mary and her bitter competing suitor Sam (Myron McCormick), a jaded organizer who sneers at “capitalist democracy.” True to its Living Newspaper origins, …One Third of a Nation… finds its core in its one-off scenes and political attitudes than the retrofitted romance narrative. When a court is convened to determine the dangerous conditions that made the fire so fatal, and punish those responsible, it’s really fattened bureaucracy that is on trial. The blame-deflecting refrain from the guilt-sharing parties is the same “It isn’t my department!” One shell-shocked witness, still wearing a thin layer of soot, stutteringly recalls the “babies burning in bed.” When he’s told he can leave the stand and go, he asks, “Go? Where?” The film’s most inspired—and unsettling—touch is the evil housing apparatus personified as a talking tenement building, which mocks and laughs at Joey (of whose increasingly troubled imagination it might be a figment). “I wish I could knock your block off!” replies Joey, awkwardly, though later he does carry out a tragic revenge. Looking a bit like Buddy Swan’s young Charles Foster Kane, the 14-year-old Lumet is quite good in the absurd role, enough that it’s a shame the experience soured him on acting thenceforth (save for a cameo in the 2004 Manchurian Candidate). But the corruption-dismantling politics clearly marked Lumet the budding bomb-throwing artist. Stock characters and cliches fill in the margins, as is the wont of agitprop. A montage of riffling front pages moves the action along. A feral pack of dead-end hooligans shuffles on and off screen, returning to comment on the action and say things like “I’ll pin your ears back!” and spit direct address taunts at “peg leg” Joey. When Cortlant lands his seaplane on the East River, they are awestruck. …One Third of a Nation… is generally kind to the heir, while Mary’s sweating, simple-folk ma and pa are contrasted with the butlered, heartless Cortlant patriarch, who urges his son to be less sentimental (the other sibling is seen happily evicting a struggling sex worker from her roach-ridden flat).

In a film powered by the leftist rage carried over from its galvanizing stage source, it’s admittedly disappointing that a benevolent savior from privilege is still valorized as a best poverty fix, and the physical contrast between the handsome, square-jawed Erickson and the less distinct McCormick does nothing to bolster socialism’s appeal. And perhaps the idea of a pampered son of Manhattan real estate money fixing the country’s Big Problems hasn’t aged well. But even if that detail, the bizarre utopian ending, and a certain stiltedness demerit the project as great cinema (especially next to golden year 1939 competition like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), these things do not detract from the film’s great interest as a historical work of resistance. Its “radical” conceits—that buildings shouldn’t murder tenants, that everyone should have healthcare and a place to live—are still next to verboten in a cultural and political climate comfortable mostly with nudging compromises just this or that side of the center. For better or worse, the forthright politics of the almost 80-year-old …One Third of a Nation… still carry the shock of truth. …One Third of a Nation airs on May 22 at 9:15 a.m. on Turner Classic Movies. Justin Stewart is a writer whose work has appeared in Brooklyn Magazine, Reverse Shot and elsewhere.