O. Henry’s Full House Cinema’s answer to trail mix, the omnibus (or anthology film) is a collection of featurettes by different directors, presented one at a time and connected by a theme or framing story. From a marketing standpoint, it’s a surefire proposition: each segment boasts its own stable of talent, contributing their services quickly and cheaply, and the poster can claim five or six times the star power of a typical feature, plus the tantalizing prospect of auteurs joining forces. As often as not, the actual effect is frustrating, with too many cooks spoiling the broth, but wherever you find a mélange of ingredients, some are bound to be flavorful. Perhaps the first known example is 1932’s If I Had a Million, an elaborate seriocomic escapade about eight randomly selected heirs to a millionaire’s fortune. Paramount spared no expense in producing it, drafting seven prominent directors including Ernst Lubitsch and Norman Taurog and most of their top stars. The film may not have set the world on fire, but recalling the shifts between zany W.C. Fields wreaking havoc on reckless drivers and Wynne Gibson’s poignant streetwalker spending a night alone in a lavish hotel, it’s clear the nascent form could elicit a broad range of emotions without strictly observing narrative cinema’s mandate for tonal consistency. After World War II, anthology films became popular in Europe, with 1948’s Quartet presenting W. Somerset Maugham’s short stories (introduced by the author) to such popular acclaim that Maugham’s oeuvre was further mined for Trio (1950) and Encore (1951). Following the success of this conceptual trilogy in the U.K., 20th Century Fox tapped the collected works of a homegrown tale-spinner for a mixed bag of period-set episodes, O. Henry’s Full House, each culminating in one of the writer’s signature twist endings.

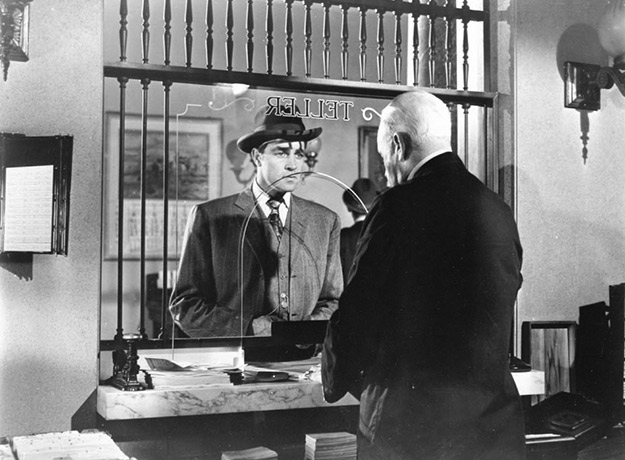

O. Henry’s Full House The stories come from the creative zenith of writer O. Henry (real name William Sydney Porter): the eight years between his move to New York City and his death in 1910, which he spent lovingly detailing the denizens of the town he called “Baghdad-on-the-Subway,” with their foibles and minor victories. The makers of O. Henry’s Full House lured John Steinbeck into providing interstitial commentary in his lone film appearance. “I’ve always felt a writer should be read, not seen,” Steinbeck declares, and indeed he’s far from a natural camera subject. Framed behind a desk or against an antique bookcase, he calls to mind Ward Bond at his gruffest, cranky at having been pressed into a suit and forced to speak lines like “O. Henry was many kinds of a writer: a social critic, a humorist, and a technician.” We might’ve been spared this précis, because the stories themselves teem with tenderness, wit, and concern for the plight of their characters, even if some are indifferently staged. The first, “The Cop and the Anthem,” concerns a genial and verbally dexterous hobo (Charles Laughton) whose plan to spend the winter in the comfortable confines of a jail cell is foiled when, time and again, his petty crimes are excused. Laughton, recalling his obdurate layabout in The Beachcomber crossed with his uprooted gentleman’s gentleman from Ruggles of Red Gap, is a marvel to watch, with David Wayne’s dimly supportive friend acting as the terrier to his bulldog and Marilyn Monroe turning up briefly as a call girl (enough to earn her star billing when her career skyrocketed later that year). Unfortunately, the episode’s director, Henry Koster (Harvey, The Bishop’s Wife), proffers the epiphany that drives Laughton to reform in exceedingly bathetic fashion, whereby even the author’s ironic turn of the screw can’t prevent a mawkish aftertaste. The second story, “Clarion Call,” sidesteps the maudlin but suffers from a fatally misjudged comic tone by the normally redoubtable Henry Hathaway. Having virtually coined the giggling psycho-killer archetype with star Richard Widmark in 1947’s iconic Kiss of Death, Hathaway and Widmark reprise the character (complete with anachronistic wardrobe) in this lighthearted tale of a cop’s debt to a gangster. The segment is nothing more than a showcase for Widmark’s broad and finally exasperating turn, leaning on his laugh like an unsteady cane and speaking in a voice that lands somewhere between baby talk and Frank Gorshin’s Cagney impression. It’s the low point of the anthology, fodder for the “blunders of great directors” parlor game enjoyed by cinephiles and schadenfreudists everywhere.

O. Henry’s Full House O. Henry’s Full House rebounds with “The Last Leaf,” a heartwarming parable about a frustrated artist in pre-gentrified Greenwich Village (“where poverty and ambition held hands,” Steinbeck tells us) and a pneumonia-stricken woman who believes that when a branch outside her window is bare, she will die. With sensitive performances by Gregory Ratoff and Anne Baxter (whose winsome frailty is well utilized), and skillful direction by Jean Negulesco (Humoresque, Johnny Belinda), who employs canted angles to convey the woman’s diseased and fear-addled state, this episode fully realizes O. Henry’s generous vision of a world where “no one is too good to slip or too bad to climb.” The final two chapters of the omnibus constitute a riposte to hard-line auteurism. “The Ransom of Red Chief,” directed by the justly deified Howard Hawks, was so poorly received for its atonally acerbic Fred Allen–Oscar Levant double act and patently silly handling of the juvenile hellion who trees his captors with the help of a bear that the segment was cut from premiere prints, and only reinstated years later. Meanwhile, “The Gift of the Magi,” helmed by the nearly forgotten Henry King (The Song of Bernadette, Carousel), elicits genuine feeling in its depiction of young love and reciprocal sacrifice, ending the anthology on an emotional crescendo. Perhaps the sentimental stories translate (and age) better than the overtly comic ones, or perhaps the workaday directors understood not to impose their own personalities on O. Henry’s. Either way, Negulesco and King provide the assets, and Hathaway and Hawks the liabilities. Nearly every omnibus film is some mix of highs and lows, but perhaps the greatest ratio of unqualified-success-to-near-miss is Dead of Night. The 1945 U.K. horror compendium features flashbacks nested within dreams and several stories that chill the blood even though they’ve become staples around the campfire and in the Twilight Zone. In the linking narrative, an architect (Mervyn Johns) is invited to a country estate in need of remodeling, but on arrival discovers he’s dreamed the weekend gathering and foreseen a gruesome outcome. To pass the time while details return to him, each guest shares a tale of a brush with the supernatural, directed in turn by Ealing Studios mainstays Basil Dearden, Alberto Cavalcanti, Robert Hamer, and Charles Crichton.

Dead of Night More cohesive than O. Henry’s Full House and united by a powerful framing story (directed by Victim‘s Dearden), Dead of Night is uncommonly potent for its juxtaposition of British reserve with hair-raising scenarios, its perception of elemental terror in banal objects (mirrors, dolls), and, above all, its uniformly artful filmmaking, marked by high-contrast lighting and gothic set design. Here again a director’s stature does not invariably correspond to the greatness of his contribution: Crichton, the man responsible for arguably the most beloved Ealing comedy (The Lavender Hill Mob) and decades later a most riotous blend of English and American sensibilities (A Fish Called Wanda), tenders a lackluster segment about a golfer haunted by a bumbling ghost that disrupts the mood like an ill-timed joke. This vignette and another, involving a haunted Christmas party, were initially expunged by American distributors. Conversely, Cavalcanti never equaled in features his short-form triumph here. The final episode concerns a ventriloquist who believes his dummy has a life of its own, a trope which has been anatomized at greater length and explicitness (from Erich von Stroheim in The Great Gabbo to Anthony Hopkins in the underrated Magic), but never as unnervingly as in Dead of Night, with the sweat-drenched, darting-eyed Michael Redgrave limning a complex portrait of schizophrenia (or is it?). All the restraint maintained over the four preceding tales suddenly and frighteningly shatters at this climactic tale. Redgrave, whose fortes were the pathos of weaklings in decline (The Browning Version, The Quiet American) and the crack-ups of men futilely racing the clock (Time Without Pity), commands our attention, creating a distinct, lewd and gregarious identity for dummy “Hugo” which contrasts with his ventriloquist’s ashen reserve. The film culminates in an Expressionistic fantasia of mirrors, tilts, and spooky-old-house trappings worthy of Cocteau. Taken as a whole, the circling plot and mutable textures of Dead of Night show how a good omnibus film can engender a nightmare— or six. O. Henry’s Full House and Dead of Night both air April 10 on Turner Classic Movies. Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.