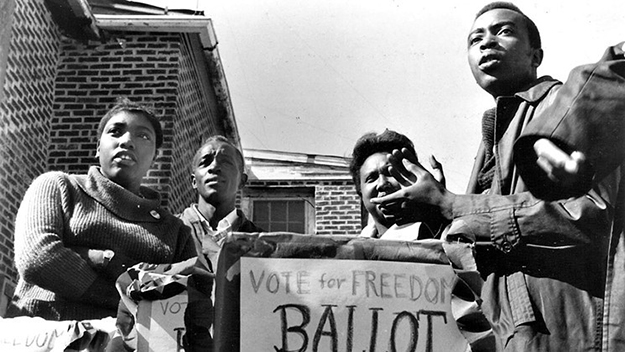

Freedom on My Mind (Connie Field and Marilyn Mulford, 1994) As the United States weathers one of the most bruising, high-stakes primary seasons in its history, what better time than the evening of “Super Tuesday” for TCM to air documentaries that place current fights for justice in crucial historical context? Freedom on My Mind (1994) and You Got to Move (1985) join a suite on “the black experience on film” that also includes vital texts like Madeline Anderson’s short I Am Somebody (1970), Robert Drew’s Crisis (1963), and George T. Nierenberg’s 1982 southern gospel show-doc Say Amen, Somebody. A tenet that unites all of these varied works is a belief in the necessity for solidarity and collective action to combat wrongs inflicted by entrenched power, a political POV conveyed largely through showing and relating lived history and fact, rather than lecturing. That these films are all centered on happenings in the American South is important—the region could very well end up deciding the next election—but should not seal off their obvious relevance to viewers in the North, West, and parts beyond. Directed by Connie Field and Marilyn Mulford and written and edited by Michael Chandler, Freedom on My Mind is a history of the Mississippi Voter Registration Project during the Civil Rights Movement, which culminated in the Freedom Summer of 1964. The film, which won a Grand Jury Prize at Sundance and was nominated for an Oscar, covers the bumpy path to more widespread black enfranchisement that opens in 1961 with almost none of segregated Mississippi’s massive black population having a right to vote. The stylistically straightforward film pulls from the standard documentary toolbox of interviews, archival footage (drawling elderly congressmen, police brutality and protests), snatches of blues/gospel, and narration to tell an alternately inspiring, enraging, and heartbreaking story that gains flavor from the vivacity and passion of its subjects. These include Endesha Ida Mae Holland, whose anecdotes begin with her rape at age 11 by white employers, through her days prostituting, which led to an organizing job with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and culminated with her legacy as a professor and celebrated playwright. Clad in a rainbow of colors, Holland flashes a big, wry smile, even when subtly flinging daggers at white enemies or recalling unutterable tragedy like the firebombing of her home that led to her wheelchair-bound mother’s death in hospital (“I don’t want to take care of that stinking black woman,” said a nurse there, per Holland).

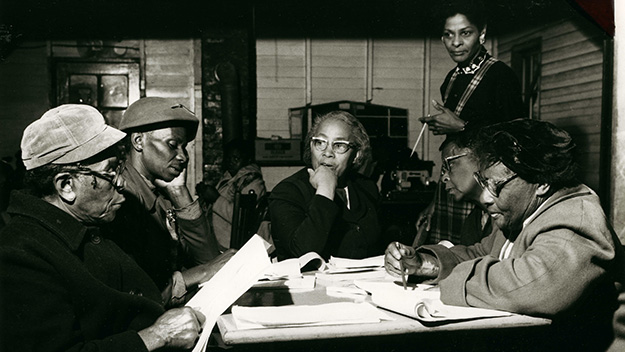

Freedom on My Mind A softer-spoken interviewee is Bob Moses, whose gentle, almost bashful demeanor belies his ferocious efficiency as an organizer and activist. This story of collective action by definition does not have one protagonist, but if it did in this case, it could be Moses. As director of SNCC’s Mississippi Project, the Harlem native traveled to Pike and Amite counties to register black voters, for which he was repaid by the establishment with beatings, arrest, and ceaseless intimidation. Though Moses escaped assassination, Herbert Lee, a local Amite farmer helping register voters, was murdered by state legislator E.H. Hurst, who predictably eschewed prosecution. Freedom on My Mind relates how this and other setbacks failed to quash the march of progress. Even the climactic showdown to which the film builds—the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City—is marred by disappointment. There, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, organized by Fannie Lou Hamer along with Moses and his powerful black and white allies and composed of common laborers, challenged the racist Dixiecrat contingent and was ultimately strong-armed by a frightened President Johnson to accept a watered-down token representation. The filmmakers’ decision to finish with this high-level, nationally broadcast letdown and not some nominal uplift (a final wrap-up does note the positive soon-to-follow passing of the Voting Rights Act and ever-increasing black political representation since) evinces their respect for the audience and their conviction that merely showing a string of wins would mute the fact that these struggles continue today, an era when parties prefer to use gerrymandering and voter-roll skullduggery to keep racialized disenfranchisement alive. Lucie Massie Phenix and Veronica Selver’s You Got to Move (the title’s from a traditional African-American spiritual) has a broader scope than Freedom: while also focused on the American South, it concerns disparate economically oppressed communities and their ideologically connected fights. Not as deep a dive as Freedom, the 86-minute You Got to Move compensates with its kaleidoscopic look at six stories which, taken together, convey the universality of workers’ essential need to keep ruling power in check. The spiritual nucleus of the film is the Highlander Folk Center, a school and social justice training center founded in 1932 and originally located in Grundy County, Tennessee, which touched each of the interviewees’ lives in some way. Co-founder Myles Horton is a benevolent returning presence, shown between segments hosing down his garden when he’s not opining on the importance of being “dedicated to the long haul” to fix the future. Attacked throughout its existence for being an alleged incubator for communism or fomenting racial strife, the school’s alumni and supporters speak of it with radiant praise as a near-utopia. One teacher there, Bernice Robinson, says the school “was the only place in the South where blacks and whites could really meet,” and the former beautician and eventual first African-American woman to run for a political office in South Carolina recalls her service teaching mostly black citizens how to read, so important was literacy as a prerequisite for voting.

You Got to Move (Lucie Massie Phenix and Veronica Selver, 1985) Just as vital was the organizing work of interviewee Bernice Johnson Reagon, a composer and scholar who was a founding member of SNCC’s Freedom Singers and, as an activist in Albany, Georgia, participated in challenging the legality of segregated public facilities—a protest that grew into one of the first citywide mass demonstrations of the Civil Rights Movement. “Unification through song” might sound quaint, but Reagon is not trifling when she recalls the work being “beyond life and death . . . When you know what you’re supposed to be doing, it’s somebody else’s job to kill you.” Also interviewed are two “ordinary housewives” who prove themselves anything but as they retell their activism in opposition to far-flung corporations trucking their toxic waste into their home of Bumpass Cove, Tennessee to dump it into local landfills. This greedily state-sanctioned activity poisoned the local water supply and has its direct topical counterpart in the ongoing Flint, Michigan water crisis. You Got to Move also features a resident of Harlan County, Kentucky, who fought for damage payments related to floods caused by strip-mining abuses, an ordeal explored at greater length in Barbara Kopple’s classic Harlan County, USA (1976). Highlander’s prime concern has generally toggled between civil rights (as during Robinson’s days there) and union/worker’s rights, a duality best personified by Bill Saunders, a former mattress factory laborer who was involved in creating a hospital workers’ organization at the Medical College Hospital in Charleston, South Carolina, which organized a successful hospital workers’ strike in 1969. Also a veteran, Saunders speaks frankly about his belief that “all white people over 30 are racist,” a conclusion he reached when he returned from the Korean War and his white buddies said nothing as he was told to buy tickets from a hole in the back wall of a bus station. Though he never completely discarded his justified racial animosity, his efforts for the hospital strike eventually convinced him that “economics are the biggest oppressive force.” The Charleston strike is the sole topic of I Am Somebody, a more wistful and poetic film than the unornamented Freedom on My Mind and You Got to Move, credit for which is due to the trailblazing Anderson, who’d previously made Integration Report One (1960), often cited as the first documentary directed by an African-American woman. I Am Somebody’s artful employment of both location and archival footage (much of which reappears in You Got to Move) gives the film a direct-cinema immediacy akin to that of Drew and associates, and helps round out a trio of bracing history lessons that double as calls to action. Freedom on My Mind airs on Turner Classic Movies on March 3 followed later by You Got to Move and I Am Somebody on March 4. Justin Stewart is a writer whose work has appeared in Brooklyn magazine, Reverse Shot, and elsewhere.