Double Suicide The wealth of older Japanese films available on U.S. home video is sometimes astounding, if you take into consideration what was released on VHS, then laserdisc, DVD, and finally Blu-ray. But the number of titles available with English subtitles, while large, still pales when compared to the depth and breadth of Japanese film history. For every Akira Kurosawa, whose entire feature filmography has been made available to English-speaking viewers on home video, there’s a Yasuzo Masumura, whose works available in translation are limited, for a variety of reasons, and represent only a tiny portion of his entire creative output. Like Masumura, Masahiro Shinoda is another filmmaker well-known in his home country as one of the primary figures of the Japanese New Wave movement of the 1960s. But Shinoda is known abroad primarily for one film, Double Suicide (1969), his highly theatrical adaptation of a Chikamatsu play, performed and shot in the style of bunraku puppet theater. Thankfully, and due to the rise in popularity of video streaming services such as FilmStruck, the Criterion-TCM partnership, more than half of the director’s exceptionally diverse filmography is available to watch at home via streaming only, including Double Suicide and the director’s other two films previously available on home video: the brilliant and brooding gangster noir Pale Flower (1964) and Shinoda’s last film as a studio contract director, the bizarre, convoluted ninja saga Samurai Spy (1965). Shinoda began his career at Shochiku Studios in 1953 as an assistant director, and in 1960 he was allowed to write and direct his first feature, made very much in the studio house style and built around the Japanese cover version of a popular 1959 Neil Sedaka song. The result, One-Way Ticket to Love (1960), was a clichéd but entertaining black-and-white youth melodrama, set in the showbiz world, about a down-on-his-luck saxophone player who gets involved with a young woman he saves from a suicide attempt one rainy night, only to watch her fall in with a handsome pop singer. Shinoda’s original script turns a critical eye on the poisonous aspects of the then-nascent talent-management culture, like its intrusions into performers’ personal lives, and it often feels like a pop-romance film from neighboring studio Nikkatsu, but with the addition of more adult themes and social realism. Nevertheless, as a debut film its naiveté is evident, a deficiency Shinoda quickly addressed in his follow-up feature.

Youth in Fury Dry Lake (1960), available on FilmStruck under its alternate title Youth in Fury, could be considered Shinoda’s true debut, in that it’s a much more mature film, addressing issues that would come up as regular themes in his later works. Again mirroring the Nikkatsu style, Dry Lake echoes that studio’s then-popular “Sun Tribe” movies by depicting the lives of bored rich kids and their dissatisfaction with mainstream Japanese society. Among them, an opportunistic poor kid (who worships dictators and has posters of Hitler, Roosevelt, and Mussolini on his bedroom walls) pinballs between a conservative politician and left-wing demonstrators, all leading to a violent finale. Dry Lake is especially significant in that it marks Shinoda’s first collaboration with three other artists who would become regular partners throughout his career. Avant-garde poet, playwright, and future filmmaker Shuji Terayama contributes a cynical and complex screenplay which not only casts a skeptical eye on the political scene in general, with its lead character alienated from both the left and the right, but also incorporates contemporary events like the then-current, massive protests against the renewal of the Japanese-American Joint Security Treaty. Terayama would go on to write four more of Shinoda’s films, most of them among his best works. Composer Toru Takemitsu, who had contributed to the soundtrack of the Nikkatsu “Sun Tribe” film Crazed Fruit (1956), turns in a jazzy score as perfectly in sync with the contemporary events of the film as his later dissonant works were with Shinoda’s more existential explorations; he eventually scored 16 Shinoda films in all. Finally, actress Shima Iwashita here makes her first appearance in one of the director’s films; she went on to appear in nearly every one of his subsequent works and the pair were married in 1967. Shinoda and Terayama continued their collaboration with Killers on Parade (1961) and A Flame at the Pier (1962), both of which are known by alternate titles My Face Red in the Sunset and Tears on the Lion’s Mane, respectively. Both films are major leaps forward in Shinoda’s career, with Flame consistently mentioned as one of the director’s own favorites. Killers on Parade is a madcap, candy-colored, pop-art nonsense comedy following a group of assassins, members of the “Killer’s Association,” who devolve to infighting when a non-accredited hit-man turns out to be a better marksman than any of them. It’s Frank Tashlin meets Mr. Freedom, filtered through the eye of Seijun Suzuki, and it’s one of the most brilliant satires Japan ever produced. A Flame at the Pier takes a more serious tone as it riffs on On the Waterfront in its monochrome tale of a rebellious rock-and-roller put to work as muscle for the yakuza strikebreakers who control the Yokohama docks in cahoots with corrupt corporate bosses. Once again, screenwriter Terayama avoids the usual clichés of the genre and no party is spared from his criticism, not even the heroic union. Takemitsu returns to the fold to contribute a terrific orchestral score, not as experimental as his regular works but reminiscent of classic Hollywood composers like Herrmann or Bernstein. Shinoda made four films between Killers and Flame, two of which are available on FilmStruck. Love Old and New (1961; aka Shamisen and Motorcycle) addresses one of his most familiar themes in the conflict between generations, but feels like a backward step for the director after Youth and Killers, with a traditional and limited view of women and a point of view uncharacteristically in step with the older generation of the story. Our Marriage (1961) is better in its examination of parent-child relations in a rural fishing village, and a family whose two daughters can’t decide whether to marry for love or for money. The ending, in which disparate groups—rural/urban, young/old, blue-collar/white-collar—all come together to move forward as a group, also seems to anticipate and encourage Japan’s economic progress in the early part of the ’60s.

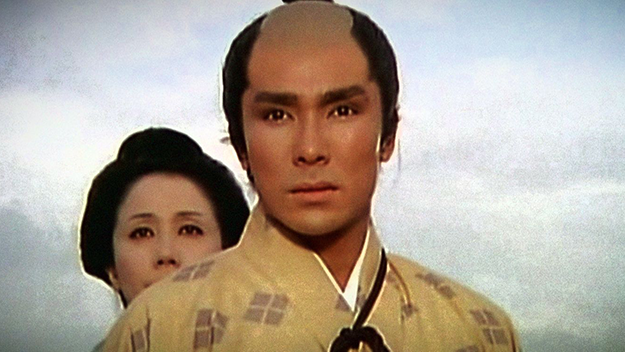

Assassin Around this time, Shinoda was being wooed by fellow Shochiku director Nagisa Oshima to break away from the company and start his own production company, but Shinoda stuck around a little while longer and closed out his studio career with three of his best films. He made his first period swordplay film with Assassin (1964)—Japanese title is actually “Assassination”—available on DVD only in the U.K. but thankfully part of the exclusive FilmStruck package here. Tetsuro Tanba stars in the stark black-and-white tale, based on historical incidents, of a disillusioned swordsman during the period when Japan was struggling with the transition from Shogunate to Imperial rule. Told heavily in flashbacks and by others’ personal testimony à la Citizen Kane, the atonal Takemitsu score combines with the avant-garde cinematography by Shinoda’s regular DP Masao Kosugi to create a genre masterpiece that’s also a stunning art film. The film looks years ahead of its time, not only incorporating hand-held shots, rare for a period samurai film, but also switching to first-person perspective for the climactic assassination, forcing the viewer to assume the perspective of the killer. It’s a complex, but breathtaking piece of cinema. Shinoda’s modern-day, color follow-up, With Beauty and Sorrow (1965) is equally powerful, with Mariko Kaga as the young student and lesbian lover of a famous painter seeking revenge against her mentor’s ex-lover, a married novelist who impregnated her two decades earlier. Based on a Kawabata novel, the film excavates the pathological and poisonous emotions of crazy women and selfish men, once again set to Takemitsu’s brilliant score. By the late ’60s, Shinoda was making films independently, though they were almost always distributed or co-financed by various major studios. The Petrified Forest (1973) is from Toho, and another adaptation of a novel, this time one by future conservative Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara, who had also written “Sun Tribe” movies during Nikkatsu’s heyday, and a pair of earlier films for Shinoda, including Pale Flower. But Forest, despite its pedigree and effective score, again by Takemitsu, feels unfocused and incorporates too many bizarre leaps of logic to be an effective film. A medical school student reconnects with an old flame, who manipulates him into murdering an abusive lover with a deadly poison the student coincidentally happens to be studying in his classes. The student’s pesky mother also gets involved, in ways which shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s seen a typical film noir, and the story turns into a rather backward-looking tale of sin and wrongdoing. Shinoda made a much better film from what was likely a better piece of original literature with his storied adaptation of Shusaku Endo’s tale of religious faith put to rigorous test in feudal Japan, Silence (1972). Screened in competition at Cannes, Silence is something of a mixed bag but comes off in the end as a powerful rendition of Endo’s novel, as well as an effective piece of cinema in line with Shinoda’s prior works. Working for the first time with Rashomon cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, the film captures wild and gorgeous locations for the story of a pair of Portuguese priests on a mission to find a lost colleague in a land where worshipping or teaching Christianity has been forbidden, under punishment of torture or death. The new adaptation by Martin Scorsese, shot in Taiwan due to a lack of appropriate locations in 21st-century Japan, trades in Shinoda’s Japanese-speaking priests for a gaggle of anachronistic, English-speaking peasants, and features as much sketchy acting in English on the part of its Japanese cast as Shinoda’s version does of the Europeans acting in Japanese. Most interestingly, though, Shinoda casts Japanese actor Tetsuro Tanba in the role of the lost friar, played in Scorsese’s edition by Liam Neeson, with Tanba acting in both Japanese and English (effectively, since he had been a translator during the postwar Occupation). It’s an interesting, and possibly brilliant choice, depicting a European character who’s “gone native” with an actor who’s obviously of a different race. Co-written by Endo himself, the earlier film’s screenplay is tighter and more focused on the struggles of the priests to survive in such a hostile environment at all, let alone carry on their teachings; it also notably ends as the novel does, with a brief coda about Rodrigo’s endeavors after he recants, instead of Scorsese and screenwriter Jay Cocks’s extremely personal (and extremely Western) addition of smuggled crosses and buried treasure.

Silence Shinoda continued to explore different elements of the period film throughout the 1970s, with his brilliant Buraikan (1970; aka The Scandalous Adventures of Buraikan), a kabuki-infused tale written by Terayama and starring Tatsuya Nakadai as a wannabe actor in love with a pricy geisha (Iwashita). Nakadai’s con man finds himself aligned with a group of anti-government cultural rebels assembled from the least respectable, lowest echelons of society, in a fight against a local politician who is outlawing petty vices in an attempt to cure the public morality. Hyper-theatrical in style, with amazing production design, it’s a surreal masterpiece. Equally surreal, though perhaps less effective in execution despite its high ambitions, is Shinoda’s retelling of the fable of the sun goddess, Himiko (1974), starring Iwashita as the titular shaman of the sun-god people, at war with the mountain and land gods for the spirits and lives of the early peoples of Japan. Produced by the Art Theatre Guild and Shinoda’s own company, it’s the kind of experimental cinema that no studio would have financed, complete with a discordant Takemitsu score, extreme violence, and butoh dancers gamboling in wild costumes and various states of undress. Himiko is, surprisingly, a perfect flip-side to Silence, with both equally about political power and religious faith, and a pair of cultures colliding violently over the two. Both films also feature impressive location photography in remote areas, though FilmStruck’s version of Himiko is unfortunately missing the final four minutes of the film, which transitions the tale of prehistory into the modern age in a surprising way; Criterion has said that this issue will be addressed soon. Shima Iwashita, so powerful in Himiko, contributed a pair of even more astounding performances in Shinoda’s next two films, though her characters couldn’t have been more different. In The Ballad of Orin (1977), Iwashita is a blind shamisen player and singer, exiled from her troupe for moral lapses, and wandering the road on her own in the 1920s Taisho period of Japan, during the country’s war efforts in Siberia. She bands together with a soldier on the run (Yoshio Harada), and the pair forge a curiously celibate partnership as they tour the countryside on the run from various parties who seek to do them harm. Beautiful and sad, with gorgeous location photography from all over Japan by Miyagawa and another fabulous Takemitsu score, it harkens back to some of the best woman-centric film stories of Japan’s cinematic history, and compares favorably with the best works of Mizoguchi and Naruse. Smaller in scale, but equally powerful, is Iwashita’s prior film for Shinoda, Under the Blossoming Cherry Trees (1975), in which she plays a samurai’s wife kidnapped by a hulking mountain barbarian (Tomisaburo Wakayama), after he kills her husband and entourage during a robbery. Manipulating him into carrying her back to his cabin, then killing his other half-dozen wives, she sets about to destroy his life, seemingly in revenge for his actions but possibly because she’s something other than human. The pair move into the capital, where Iwashita’s character encourages her new husband to bring her fresh heads of noblemen and merchants, which she treats as toys or pets. The macabre story finds the pair slowly going crazy together, and the final third takes a dive into horror, making it one of Shinoda’s most atypical films but a genre classic in its own right, with Takemitsu’s jangling score setting the perfect macabre tone.

Gonza the Spearman Iwashita also stars in Shinoda’s later period film Gonza the Spearman (1986), which took the Silver Bear in Berlin and, like Double Suicide, was based on a Chikamatsu play that follows a pair of adulterous lovers on the run. Miyagawa and Takemitsu contribute once again, and although the first half of the film setting up the pair’s flight is a bit rote and conventional (featuring far too many plot devices advanced by one character clandestinely overhearing the conversation of another), the movie gets its blood boiling during the second half, which depicts the injustice of their plight and the rage of Iwashita’s family, who want to kill her for her shameful misdeed. It all culminates in one of the most shocking and well-staged swordplay sequences in any of Shinoda’s films. Shinoda retired from filmmaking after his 2003 espionage epic Spy Sorge, and only made a half-dozen films after Gonza, but one of them is also part of Criterion’s FilmStruck streaming package, and it’s a wonderful piece of entertainment, even if it’s not quite in the same league as the director’s earlier output. Moonlight Serenade (1997) echoes—perhaps intentionally—the nostalgic works of Nobuhiko Obayashi (most notably his 1986 wartime coming-of-age saga To the Fields, Mountains and the Seacoast) in its flashback tale of a man, his memory stirred by news footage of the Kobe earthquake, who remembers his childhood there during and after the war. Most of the film takes place on a ferry making the long crossing between the Japanese mainland and southern island of Kyushu, with a rogues’ gallery of characters crisscrossing the episodic plot, all of them carrying various secrets or regrets left over from the war, and a hope for a brighter future. None of it is particularly weighty, but the nostalgic perspective was very popular in Japanese film at the time. Shinoda includes both a benshi silent film narrator who treats the other passengers to an illegal screening of a Tsumasaburo Bando samurai movie—outlawed by MacArthur’s Occupation edicts—and a sequence in which the main character’s father takes him to see Casablanca at a local theater. It’s the kind of sentimental celebration of cinema easily excused by fellow film-lovers. Marc Walkow is a writer and film programmer living in New York. Formerly a director of the New York Asian Film Festival, he has also produced DVDs and Blu-rays for Criterion and Arrow Video.