Danny Says

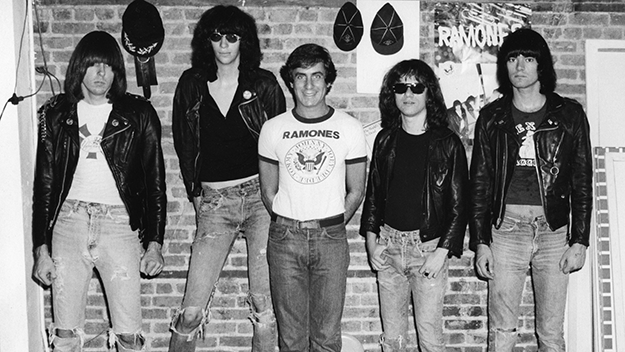

“If I went to see an artist now, I would say, ‘Well, I really like you and I’ll work with you, but you’ll only be rich and famous in 40 years,” Danny Fields, the subject of Brendan Toller’s cheeky documentary portrait, told FILM COMMENT in an interview. If you didn’t know Fields from Adam, after watching Danny Says you might notice him eerily materializing in pictures you have seen a hundred times before, right next to Andy Warhol and Lou Reed or Iggy Pop and Joey Ramone. Publicity agent for the Doors, director of publicity for and champion of acts like the Stooges and MC5 at Elektra Records, and manager of a small, unknown band called the Ramones, Fields has spent the better part of his life nudging the mainstream toward underground music. While Fields may not have grown famous off his work, he elevated the careers of iconic artists like Leonard Cohen, Nico, Judy Collins, Iggy Pop, and Patti Smith. Toller, whose first documentary I Need That Record! paid tribute to independent record stores and crate-diggers, wisely allows Fields’s meandering recollections of 1970s New York to structure the film. For Fields, playing mediator between record executives and insane and insanely talented artists like the Stooges (who, by Iggy Pop’s gleeful admission, made a sport of blackening Fields’s reputation at Elektra) could sound like hell, but he had a simple and urgent motive. “I wanted people to like what I liked,” he said. “I knew, always, that the first reaction will be that most people won’t like [the music I like]. Most people don’t like it, but the people that do, like it passionately.” Crafted through several years of interviews with Fields, with full access to his extensive personal archives, Danny Says is as mischievous and bitingly funny as its 75-year-old subject. As if to suggest Fields is too restless for a conventional talking-head/still-photograph format, Toller utilizes animated sequences by several artists including a surreal illustration by Emily Hubley of Danny’s experience being walked through an acid trip by Leonard Cohen and Judy Collins. Fields is a documentarian in his own right, in the sense that his apartment is crammed with years of rare photographs and footage. Unearthing such material, from innumerable portraits of his favorite bands to an audio recording of Lou Reed listening to the Ramones for the first time, is one of the joys of Danny Says. “After five years [of managing the Ramones] all I have to show in terms of my success as a manager is nothing. On the other hand, I took lots of pictures of them because as manager, I had nothing to do,” said Fields. “I wasn’t in it to get a body of photographs, but it turns out the body of photographs I got is good enough to be a book.” The collection is slated to come out next year, and the Yale University Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library recently acquired a large chunk of Fields’s archives (with the exception of his “racy home movies”). Fields has more or less retired from attempting to force culture on the masses (unless you count Danny Says). But with wisdom gleaned through age, he has one final potential contribution to work on: “You can’t have porn without smell-o-vision. And that’s been my big frustration always.” Station to Station Multimedia artist Doug Aitken’s first feature-length film is not edited so much as it is composed. In 2013, Aitken traveled the length of the U.S. by train with a rotating cast of artists and performers, and staged 10 happenings along the way in cities including New York, Kansas City, and Santa Fe. Station to Station is the frenetic product of the resulting mass of footage, shot both on and off the train, and here organized into 62 one-minute short films each of which depicts artwork, music, locations, people met along the way, and often all of the above. The trancelike merry-go-round of participants sees Patti Smith next to professional whip-crackers next to Dan Deacon next to Greg, the engineer of the train. What emerges are the specific rhythms of each locale, the dissonances and unlikely harmonies produced between dissimilar musicians, and crescendos of creative energy generated along the train’s journey. Aitken is obviously no stranger to working in video. His 2007 Sleepwalkers and 2012 Song 1 projected video art onto the exteriors of the Museum of Modern Art and Hirshhorn Gallery respectively. Station to Station pushes Aitken’s fascination with the effects of modern technology on human consciousness to extremes by setting the creative process itself into literal motion, forcing artists to create in a state of constant physical displacement and change that mirrors what Aitken perceives as our psychically fragmented and physically rootless existence. “There is definitely a restlessness to the film. There’s this sense of change and acceleration,” Aitken said. “But at the same time, in the end I was hoping the film could put you in the present.” Station to Station gleefully capitalizes on the modern attention span, and while watching trains of thought collide, connect, and glance off one another at every turn, the viewer is forcibly placed in the present. Translating three weeks into 62 minutes, Aitken wanted to create a film “where you’re not drifting off into memories, or wondering what’s going to happen next—you’re just kind of engaged in the present and it’s moving with you, and it’s moving at a rapid rate.” Station to Station produced an enormous quantity of music, by collaborators as diverse as Mavis Staples, Beck, Jackson Browne, No Age, THEESatisfaction, and two different marching bands. Removed from their separate studios and niches, Aitken’s experiment in creative dislocation comes to a head when artists jam informally and connect across superficial aesthetic barriers. “There’s a kind of violence and harmony you hear,” says Aitken. “Musically it’s a transcendental moment because you hear these people starting to tap into something which is much larger than themselves. It’s beyond self and beyond ego, and the sounds around them are actually leading the composition that they’re just making on the spot.” With no warning as to what you’ll see next—Thurston Moore and Ariel Pink jamming, or Cat Power taking a detour to sing solo in a cave—there is little to do but sit back and enjoy the ride. Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story

According to his wife, former Ink Spot Stanley Morgan used to brag that his son Frank was the greatest musician in the country, but… That long pause could be followed by any of several descriptions: criminal, addict, prison inmate. Frank Morgan’s life was full of such ellipses. Morgan grew up as Charlie Parker’s bebop protégé, invited to tour with Duke Ellington at 15, backing Billie Holiday at Club Alabam during the height of the Central Avenue Jazz Scene in Los Angeles by 17, and incarcerated by 30. In addition to enormous talent, Morgan shared with Parker a heroin addiction, and he spent the next three decades on the revolving-door circuit through San Quentin prison while the name “Frank Morgan” remained a secret cultural handshake in only the most knowledgeable circles. Morgan’s story of unruly talent fettered by self-doubt and stubborn self-destruction is hardly unique, particularly after heroin infiltrated the jazz scene following World War II. But it’s Morgan’s music that first attracted filmmaker N.C. Heikin, who previously directed Kimjongilia, about North Korean prison-camp survivors. “It wasn’t actually his narrative, it was his music,” Heikin explained. “He’s a very mellow, melodic, lyrical player. No one compares to him in terms of tone, the sound that he makes with his saxophone.” The battered resilience of Morgan’s saxophone, smooth like well-worn leather, forms the unshakeable emotional core of Sound of Redemption, which centers on a tribute concert performed at San Quentin in Frank’s honor by modern jazz musicians such as Ron Carter, Mark Gross, Grace Kelly, and Delfeayo Marsalis. While some of his idols died from their addiction, Frank’s narrative blessedly allows for a happy third act. After marrying Rosalinda Kolb and vowing sobriety, Frank made a surprising comeback with a slew of albums after 1985. His friends and relatives had long since learned to live with a niggling sense of uncertainty, so Morgan ultimately surprised no one more than himself. In Heikin’s big-hearted film, Kolb calls Frank “the man that you forgive and forgive,” a phrase which lingers long after the credits roll. The conversation Heikin orchestrates between past recordings of Morgan’s music and the present-day tribute transcends the seeming disharmony between Frank the mythical underground saxophonist and Frank the addict and criminal. Legends of Ska: Cool & Copasetic

With the second wave of ska emerging as “Two Tone” in London and the third wave blending with punk in the United States, ska is a strong candidate for the poster child of cultural appropriation. Brad Klein’s documentary Legends of Ska: Cool & Copasetic is a welcome reminder of the very specific cultural climate ska grew out of: Fifties and Sixties Jamaica, where ska played an invaluable part in developing Jamaica’s music scene in the days before independence from Britain. “When it first started, people didn’t believe that Jamaicans would actually back their local artists so much,” Dennis Sindrey, a guitarist who recorded on many original ska tracks, said by phone. “In those days most of the records they bought were coming from the USA.” For Minneapolis DJ Brad Klein, Legends of Ska has been a passion project long in the making. During the summer of 2002, he orchestrated a concert in Toronto that reunited influential musicians present at the birth of ska including Sindrey, Prince Buster, Derrick Morgan, Stranger Cole, Lord Creator, and Patsy Todd. Ska fans will recognize and appreciate the care and detail of Klein’s portrait of the scene, touching on the fabled Sound System dances of the Fifties and the birth of Federal Records. Legends of Ska exudes a palpable love for the jaunty, danceable rhythms of ska, and Klein’s camera can be caught gazing in awe at figures he clearly venerates. The standout interview comes from Patsy Todd, a genial Jamaican native that Klein’s camera catches tittering after her first performance in decades. Todd once enjoyed a brief stint of stardom with duets like “Housewife’s Choice” until, fed up after being denied fair compensation by shady producers and creative control because she was a woman, Todd swore off the scene to spend her life as a secretary for a hospital in the United States. Visual documentation from the early ska period remains scarce, since few musicians owned cameras at the time. In looking for footage, Klein blindly bid on home movies shot by tourists during the Sixties, wagering that they may have captured performers like Sindrey performing at resorts for a steady paycheck. Still, Legends of Ska is primarily an oral history and much of Klein’s information comes from a series of interviews he conducted with musicians during the 2002 reunion concert. “He had like 15 of the greatest artists of that time in that concert,” Sindrey said of the all-star gathering. “And it can never be duplicated, because more than half of them have died since.” Legends of Ska makes a persuasive case for the ability of documentary to preserve a piece of fading culture as its innovators, and the music they created, seem to slip away before our eyes.