Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966) For the queer American cinephile, the films of the various European new waves and international art-house boom of the 1960s can be as alienating as those of classical Hollywood cinema. As radical as they may often have been in form, the majority of the era’s most venerated western male art-house filmmakers doubled down on masculinist heteronormativity, just with a self-aware intellectual edge: in purporting to tell more direct truths about the distinctions between men and women, such directors as Godard, Truffaut, Rohmer, Antonioni, and Fellini ended up making films that focused almost exclusively on the mysteries of traditional male-female relationships, but in the guise of deconstructive inquiries. This is not to lessen the accomplishments of great, irreducible films like Last Year at Marienbad, L’avventura, or Masculin féminin, complex, richly imagined, and endlessly regenerative works that did more to push narrative cinema forward than most films that might look more superficially progressive in the rear-view mirror, but to point out that even in the most hallowed era of thrillingly reimagined, politically awakened cinema, gay themes and characters stayed as marginalized as ever. Evidence of queerness—whether in the ostensibly straight films of gay director Jacques Demy, or in the teasing MMF ménage narratives of Jules and Jim or Knife in the Water—remained subtext, much like in the mainstream American cinema these films were often explicitly positioning themselves against. At the same time, the querying of the stability and permeability of heterosexual relationships that defined so many of these films, from Breathless to 8½ and beyond, gives the queer viewer a lot to hold on to. After all, what fills the gaping hole wrought by the soul-sickness of a film like L’eclisse anyway? Lumping all these films together in any serious way may do a disservice to them, but for generations of cinephiles, these films inadvertently did form a kind of genre, one that made itself felt as an “alternative” cinema but which can feel like its own rigid canon.

Of all the Great Masterpieces of the era, Ingmar Bergman’s Persona is often cited as among the most queer-friendly, or at least exploratory, and indeed it sometimes seems the most equipped to provide a way out of the constricting binds of aesthetic and sexual traditionalism. Nevertheless it’s always been a tricky film to parse in the way it represents the unbearably intimate relationship between its twinned protagonists, Elisabet (Liv Ullmann), the theater actor who suddenly has gone mute in the middle of a performance of Electra; and Alma (Bibi Andersson), the chatty nurse assigned to take care of her. Absconding to a remote seaside cottage (set, of course, on Fårö, Bergman’s eventual fortress of solitude), the two women undergo a series of profoundly emotional transferences and metacinematic transformations that fling the film into a place of unsettling, poetic abstraction and, for the women on screen, emotional incertitude. As non-narrative and liminal as the film becomes, entering into a realm that exists outside of time, space, and logic, Persona also only truly “makes sense”—if one desires such a thing—as a romantic relationship drama. All of the film’s pathos, the fears, the jealousies, and the eroticism that bubble to the surface are legible within the framework of a love story, from meeting to blossoming romance to dissolution. In fact, if looked at through the right queer lens, Persona could be among the most penetrating break-up movies ever made. For a film so intensely claustrophobic, Persona has an unmistakable sense of freedom; from one scene to the next, it’s beholden to nothing so much as its maker’s imagination. Its feeling of liberation comes from a profound despair, however. No New Wave whippersnapper, the nearly 50-year-old Bergman, who had been making films for more than 20 years, found himself at one of his lowest points, recuperating from depression and a lung infection, when he conceived the film. The film is shot through with a deeply felt shame of the self, both plunging forthrightly into its intimacies while also recoiling from them. In Persona, the body is a locus of eroticism and terror.

Though Elisabet and Alma haunt each other in various ways throughout the film, even at times appearing in the backgrounds of shots like wraiths emerging from vapor, the true specter here is heterosexuality. Elisabet’s sudden refusal to speak is concurrent with her rejection of marriage and child—when Alma reads aloud a letter to her, assuming the voice of her husband, Elisabet furiously crumples the paper and proceeds to rip in half a photograph of her son that had accompanied it. As with everything, the provenance of Elisabet’s unhappiness remains unspoken. By the same token, Alma, though wildly garrulous in comparison, appears often besieged by some kind of imprecise sadness and frustration, her seeming emotional transparency and willingness to share anecdotes masking an inner disruption possibly even more consuming than that of Elisabet. Since Alma’s given to amused observations or distressed extended monologues, we technically learn more about her, but we may leave the film feeling that we know less. And her most memorably exposed moment—performed by Andersson in a state of hectic confusion, as though she doesn’t know exactly why this is being extracted from her—comes when she relates a traumatic-desirous memory of when she and a close female friend named Katarina succumbed to a spontaneous outdoor orgy with two young male strangers who had been spying on them as they sunbathed. As related by Alma, the eroticism of the moment seems located entirely in the transaction between her and Katarina: recalling their rubbing suntan lotion on one another, the realization that they’re being penetrated by the same, nameless man. In light of these revelations, Persona’s subliminal opening “gag”—a blink-and-miss-it, three-frame shot of an erection spliced rudely into the beginning of the epochal, film-stream-of-consciousness prologue—feels like a somewhat less unmotivated intrusion. Andersson and Ullmann share the screen in such aggressively intimate compositions, and are captured in such startling close-up by Sven Nykvist, that Persona was destined to be scrutinized for Sapphic undertones. Yet though over the years the film has been occasionally taken to task for succumbing to a kind of vague lesbian chic (especially coming just three years after Bergman’s The Silence, in which a Freudian attraction complicates an alienated, disassociated woman’s relationship with her sister), the connection felt between Elisabet and Alma is hardly a tease. For Alma, who always wanted a sister but was saddled with brothers, Elisabet functions as a repository for her neuroses but also unspoken desires (“I think you’re the first person who’s ever listened to me”). The women are physical with each other, gentle and persuasive in a way that goes beyond a doctor-patient relationship, but which stops short of being literalized as sexual. It’s something more palpably erotic—the sense of becoming one with another person, of the body entering the realm of the mind.

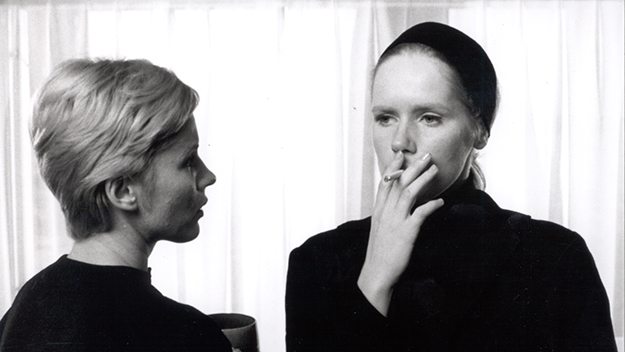

Late one night, as the two women sit together in the dining room, Alma nodding off, we hear a voice whisper, hushed yet clear as a bell, “You ought to go to bed or you’ll fall asleep here at the table.” The back of Elisabet’s head faces the camera, so we can’t be sure these were the mute woman’s first spoken words in the film. Soon after, in the wee hours of a sinister morning, near-dawn light casting a ghostly spell, Elisabet appears as though a phantom in Alma’s bedroom. Then, in one of the film’s most recognizable compositions, the two women look into the camera (are they looking at us, or themselves in an unseen mirror?) side by side. Elisabet sweeps her hand across Alma’s short, boyish hair before moving her lips across the back of her neck in a gesture that all but dissolves the image before it becomes a kiss. In his excellent 2013 study Queer Bergman, a book-length challenge to the standard line about Bergman as a traditionally heterosexual male art-house auteur, Daniel Humphrey writes surprisingly, amusingly little about Persona, yet he does speak to “this celebrated image,” which “indirectly reasserts the heterosexuality of the male cinematic gaze.” He then adds, “With Persona’s thick layer of cinematic self-reflexivity, however, the film’s construction and deconstruction of a female-desiring spectatorial position also serves to distance the spectator from any sense of secure gender-based subjectivity.” It’s a film of doubles and split selves, yet there is no simple binary here.

The next morning, while the two women stroll on the nearby rocky shore, Elisabet denies everything: that she spoke and that she was in Alma’s room. Whether Alma’s hazy memories were fantasy or not, Elisabet’s denial is tantamount to a rejection. Soon after, en route to mailing a letter Elisabet has written to her husband, Alma opens and reads the note to discover that she has mocked Alma for being “smitten” with her and relates her personal stories told in confidence—of her orgy, of her abortion. From this point forward, their relationship becomes retaliatory and remorseful, deranged by mistrust, jealousy, and scorn. After accidentally breaking a glass on the back patio, Alma intentionally leaves a single jagged shard outside the door, awaiting the careless step of a barefooted Elisabet. The increasingly unhinged Alma screams at Elisabet—the ostensibly mentally ill of the two—for being “rotten” and a “liar,” before summarily begging for forgiveness. Often Alma’s one-sided dialogue has the effect of making her seem like she’s talking only to herself, as though her rage is being constantly and unconsciously directed inward. Yet if Alma is wracked with self-delusion and guilt, where does it come from, and, perhaps more importantly, what does it mean if she and we can never find out? Persona is a depiction of split consciousness, visually evoked by Bergman and Nykvist as a series of endlessly proliferating doubles, mirrors, and repetitions, as well as an ontological investigation into its own properties. Late in the film, when the linear narrative has completely crossed a sensory threshold, the same monologue—in which Alma narrates the story of Elisabet giving birth to a child she instantly loathed—plays twice through, the camera fixed first on Ullmann listening in anguish, the second time on Andersson, overcome with accusatory indignation. In addition to foregrounding their performances as performances—and underlining the cinematic apparatus by forgoing shot-reverse shot editing in favor of essentially running two takes of the same scene back to back—the gambit merges the women’s experiences so completely that it feels as though they’re addressing their own psyches from within a deep chasm. At the end of the scene, their faces merge into one in a freeze frame, a shock technique Bergman achieved by combining the “unflattering” halves of each of the women’s faces, the interior made visible.

A terrifyingly open text, Persona interrogates many things—the limits of language to adequately express innermost feelings, the vampiric nature of human relations, the impossibility of genuine individuality, the essential performativity of everyday interactions, the “reality” of constructed art—and as a result its main characters become the most abstract concepts of all. That Alma and Elisabet’s attraction-repulsion remains so difficult to parse so many years later strikes me as testament not to a vagueness or unwillingness on Bergman’s part to allow them to fully inhabit their desires but rather to the director’s understanding of the essential malleability of human sexuality. Searching for definitive signs of queerness in Persona might be as much of a fool’s errand as assigning any single, deliberate intention to it, but it’s also one of the few films of the era that gives itself over almost completely to the unconscious without making room for postulating about opposite-sex attraction. Nothing in Persona is strictly defined, maybe even gender. After all, we’re made up of unpredictable, unreadable gestures and motivations, just as, sometimes, like Alma and Elisabet, we’re made up of light on a screen, and, as the ending reminds us, one only need turn off the projector to make us disappear. Michael Koresky is the Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy at Film Society of Lincoln Center; the co-founder and co-editor of Reverse Shot; a frequent contributor to The Criterion Collection; and the author of the book Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press.