Flaming Creatures (Jack Smith, 1963) “Hollywood has created an image in the minds of the people that cinema is only entertainment and business. What we are saying is that cinema is also art. And the meanings and values of art are not decided in courts or prisons.” These words, written by Jonas Mekas, were published in the pages of Film Comment magazine in its Winter 1964 issue. The sentiment in the first of these sentences would only become more glaringly obvious as the years wore on. The second sentence conveys something that most people would agree with as a truism in spirit, if not necessarily practice: after all, what does it mean to call something “art” and what do we do with it once we’ve designated it as such, and how often do we seek it? The third sentence is more concrete and situates this short essay—titled, simply, “Statement”—in the precise moment it was written. On March 3, 1964, New York police interrupted a screening organized by Mekas of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures at the New Bowery Theater, seizing the 16mm print and projection equipment, and arresting Mekas, along with Ken Jacobs (the theater manager that night) and Florence Karpf (the future Flo Jacobs, taking tickets), on charges of obscenity. The case remains one of the most notorious public battles over artistic freedom of expression in American movies. One could say that it obscures the object at the center of the controversy, although the historical knowledge of Smith’s extraordinary work becoming political grist has at least done the service of elevating one of the most beautiful and radical of all experimental films, a devil-may-care spectacle of intense queer desire, into the realm of importance.

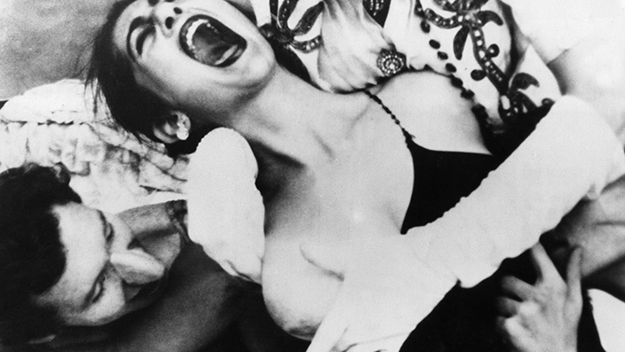

That dreaded “I” word is a designation that Smith himself would bristle at for decades thereafter, as his film’s riotousness was fashioned more for knowing laughs than lofty significance. Nevertheless, Flaming Creatures, as most great works of art should be, can be two things at once; it’s an earth-shaker that also pokes at enough pleasure centers to give off a false whiff of frivolousness. “I started making a comedy about everything that I thought was funny,” he would later say, and would refer to the fact that the film’s earliest, perhaps queerest, audiences “were laughing from the beginning all the way through.” The film’s precarious nature as both uproar and uproarious spoof was also negotiated in the April 13, 1964 review for The Nation by staunch Creatures defender Susan Sontag, who writes: ”The only thing to be regretted about the close-ups of limp penises and bouncing breasts, the shots of masturbation and oral sexuality, in Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures is that it makes it hard simply to talk about this remarkable and beautiful film, one has to defend it.” Speaking of defense, Sontag would be called upon to literally testify to the film’s status as art in the courtroom. History has proven that the excitement and amusement afforded by the experience of watching Smith’s film is not diluted or compromised by its status as a political cause célèbre. At the time, surely far less people would have actually seen Flaming Creatures than had read about People of the State of New York v. Kenneth Jacobs, Florence Karpf and Jonas Mekas, heard on June 12, 1964, and resulting in jail sentences—ultimately suspended—for Mekas and Jacobs. Today, one can be aware of the sensation it caused but also be free to live in its moment, luxuriate in its assaultive dynamism. Flaming Creatures feels entirely new, fresh, thrilling, and aesthetically subversive in its 57th year (the age Smith was when he died of complications from AIDS in 1989). Despite this, I’m not sure if there’s something new that I can really say about Flaming Creatures at this point. Except perhaps this: an online re-watch gave the already degraded image of a film shot on out-of-date 16mm Army surplus Kodak stock with a 300-dollar budget an even more ghastly, ghostly feel, which was both lulling as a late-night viewing party-of-one and also depressing beyond belief. Though grateful I could access this stone-cold classic for the couch, I realized I wanted nothing more than to experience its ravishing queer bacchanalia where it was meant to be seen, on the big screen, preferably at Anthology Film Archives, which Mekas cofounded in 1970 and where Flaming Creatures shows regularly as part of its Essential Cinema series (long may it live). Nevertheless, the erotic extravaganza of Smith’s masterpiece remains unquenchable even when mottled by pixels and muffled by tiny, tinny speakers. Flaming Creatures is all impulse, untrammeled and vibrating. It’s the last movie Smith ever finished, which makes a lot of sense for an orgiastic film that seems completely spent, wallowing in its own excessive, repeated climaxing. Shot on the rooftop of an abandoned movie theater, with a group of friends giving themselves over body and soul to play various bedazzled, defiled creatures, the film refashions cinema as camp crescendo. Smith had direct reference points, from Josef von Sternberg melodramas to the Technicolor adventure films of Dominican actress and unlikely forties Universal star Maria Montez (music from Montez’s Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves is used early in the film), but no preparatory knowledge or academic readings are entirely necessary to enjoy the overall tumult of the film. In Flaming Creatures, men and women alike are whipped into a frenzy of queer movement; the most memorable repeated image is of the camera swanning and swooning over a tangle of bodies. At first a viewer might try to “figure out” who’s male and who’s female, before giving up, and then realizing that giving up is the point: male and female become one writhing mass. The film is somehow both hypersexualized and asexual, its images of lolling penises, groped breasts, and armpit hair less arousing than merely flaunting, more like middle fingers than erections, directed at a hopelessly square world of commercial interests that go a long way toward deadening a culture.

Sex is inextricable from pageantry in Flaming Creatures; it’s a film that coasts on the waves of a liberating androgyny, visually registered in the actors’ makeup and costuming. Men apply phallic lipstick in “flawless lines”: though the black-and-white film can’t convey the “pure peach” and “luscious cherry” of the lipstick, the colors all but pop off the screen, accompanied by the wondrous and somewhat nauseating sounds of puckering. Grand Ole Opry country singer Kitty Wells’s 1952 song “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honkey Tonk Angels” provides counterpoint to scenes of these frisky demons primping and writhing (“Too many times married men think they’re still single . . . It’s a shame all the blame is on us women”). From here things get more intense, as though we’ve been carefully preparing for the binger of the century: nipples kneaded in close-up, a dress unceremoniously pulled up to rudely reveal genitals, groping that crosses the line—if there ever was a line—into a kind of primitive rape scene, enhanced by ear-piercing, overlapping screeching on the soundtrack. Hedonism mutates into vampiric, almost cannibalistic behavior, and as the camera shudders and quakes, we begin to have the feeling of taking part in an orgy inside of a tornado. Flaming Creatures hasn’t stopped shaking film culture; it keeps turning up in the conversation. In October 2015, a New York Times article reported that Gerald Harris, the Manhattan assistant district attorney who first prosecuted Mekas for the screening, reached out to Mekas to apologize, writing in an email: “Although my appreciation of free expression and aversion to censorship developed more fully as I matured, I should have sooner acted more courageously.” Just last year, critic Jonathan Rosenbaum ran into a quite contemporary version of a censorship snafu when Facebook temporarily suspended his account for posting a still from Smith’s film. Of course, it’s at theaters like Anthology Film Archives and Museum of the Moving Image where Flaming Creatures truly lives on, screaming and naked as the day it was born. Just as essential as the film itself is the writing that it spawned, from Sontag to Hoberman to Rosenbaum, and surely for all the creatures who have yet to discover it. Mekas’s statement in Film Comment is particularly crucial, an eloquent, necessary defense of both Flaming Creatures and of Jean Genet’s oft-banned short Un Chant d’amour, which he defiantly screened in continuous showings just one week after his arrest to help benefit his legal defense. Today Mekas’s statement in Film Comment is a reminder of something this is indeed capital-I important—a press that’s not only free, but that cares—a critical community that thrives on the maintenance of challenging creative expression. It’s one thing to stand up for artist’s rights; it’s another to care enough to stand up for art itself in the face of relative moral chastity. Michael Koresky is a writer, editor, and filmmaker in Brooklyn. He is cofounder and editor of the online film magazine Reverse Shot, a publication of Museum of the Moving Image; a regular contributor to the Criterion Collection and Film Comment, where he writes the biweekly column Queer & Now & Then; and the author of Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press, 2014.