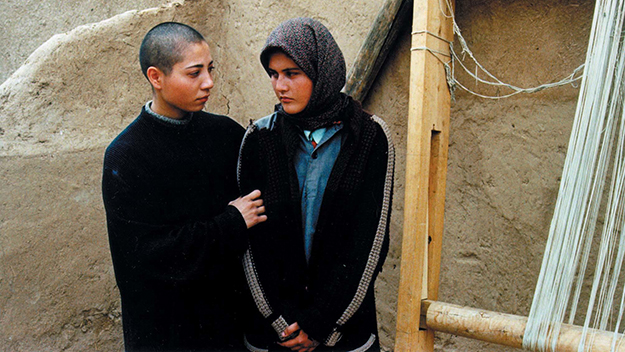

Images from Daughters of the Sun (Maryam Shahriar, 2000) In a 2001 interview, Iranian director Maryam Shahriar spoke about the genesis of her 2000 film Daughters of the Sun, which won Best First Feature at the Montreal World Film Festival. After attending the University of California, Shahriar returned to Iran to care for her sick mother. She had decided cinema was what she wanted to do. But how? Iran’s filmmaking community is small; she already knew some of the players. Shahriar said, “I called [Abbas] Kiarostami and I told him that I felt miserable, that I thought about killing myself. And he said: ‘Don’t ever do that! I know you’re stronger than that. Just write something.’ And I said: ‘I can’t write. There’s no way that I can think about anything else than my real situation.’ But he said: ‘Oh, try, do your best!’ And I did!” The screenplay she wrote as a result of the great director’s prodding was not Daughters of the Sun, but it jump-started her into action. She joined the Directors Guild. She made a few short films. A producer told her to write another screenplay. Again, she balked, but then: “Something strange happened to me again, I saw an image of a woman’s head being shaved, and from there I began. That was all I had, this image. And then…this story came along. The minute I called the producer to tell him the new story, he said: ‘It’s fantastic.’ So we took it on from there.” This helps explain Daughters of the Sun, a grim film told in a non-literal way where the images create space for the unconscious to operate, similar to images in a dream. There is the main story, but it is constantly interrupted with images of tremendous symbolic resonance. Bare wintry trees filled with cawing crows. A black riderless horse galloping across a field. A rusty carnival ride sitting beside a quiet river. Even in scenes filled with people, there is little dialogue. Daughters of the Sun is practically a silent film. In the opening sequence a young woman named Amangol (Altinay Ghelich Taghani) shaves her head, dresses as a boy, and goes to work for a rugmaker in an isolated village. “Hired” as an apprentice, she is put in charge of three weavers, all women. The “Master” is a brute who beats them all regularly. The other weavers are locals, but Amangol, now called “Aman,” stays in the workshop overnight, door locked from the outside. Amangol’s disguise is presumably meant to shield her from the dangers of being a women, but there are creepy moments when she thinks that someone—a vagabond musician, a lady in the next house—might suspect her secret. Her boy-disguise doesn’t protect her from violence, but her talent as a weaver makes her necessary. “He’s just a kid but weaves like the old masters,” the Master brags to a friend. One of the other women, Belghies (Soghra Karimi), sends curious looks over at Aman as they work at the vertical looms. When you learn the harrowing details of Belghies’ life, it’s not a surprise she is drawn to the quiet young man who doesn’t behave like other men. In a breathtaking moment, Belghies begs Aman to marry her. There’s a long silence, and Aman—who barely speaks throughout—says: “All right.” Whether or not Belghies suspects Aman is a girl is an open question. There are clues she does know. As Dave Kehr pointed out in his piece on the film for The New York Times, this is not an Iranian Boys Don’t Cry (even though it was billed as such). Much is left unspoken. In one extraordinary scene, late at night in the empty workshop, Aman puts on a flowered skirt left there by one of the workers. It’s a moment of transgression: she glories in the now-forbidden sensation of a skirt. So, you see, it’s complex.

Cinematographer Homayun Payvar, who shot Kiarostami’s famed Taste of Cherry, also shot Daughters of the Sun, and his gift with light, shadow, framing—in vistas and in closeups—is an enormous contribution. So much of the film takes place in the basement workshop. At times, it is a prison. At times, it is a womb. The dark shadows are punctured by the hanging balls of colored yarn, so vivid they almost glow. The images have real staying power. You don’t forget them. In one scene, a wedding party marches grimly through a grove of trees, the women half-heartedly ululating, the men tiredly beating on drums. (I was not at all surprised when I learned Shahriar decided to become a filmmaker after seeing Fellini’s 8 1/2.) Hossein Alizadeh composed the haunting score (in, perhaps a coincidence, he also scored Moḥsen Maḵmalbāf’s 1997 Gabbeh, which features a “gabbeh,” a traditional type of Iranian carpet). When I first saw the film, I found some of the visual “motifs” a bit cumbersome. Over the years, I have changed my opinion. The motifs are established early, and repeat in variations. The black horse. The escaped donkey, with bundles of yarn on his back, wandering through the fields, a beast of burden no more. For the entirety of the film, a man in a jeep tries to locate the village. We learn his purpose only at the end. There’s also that rusty Ferris wheel Shahriar keeps returning to, another Fellini-esque touch. These images evoke movement, free time, and pleasure, all of which are barred to Aman and Belghies. Aman and the women hurry to complete a rug for a wealthy merchant. The pressure is intense. The outside world feels a million miles away in this unheated structure with no electricity, but the connection is undeniable: these rugs command hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars in the Big Business that is “Oriental rugs” and are, in some cases, made by women living in indentured servitude and working in the harshest of conditions. The critic for the Village Voice wrote in her review of Daughters of the Sun that “the relentless hardships [Aman] undergoes soon become wearisome.” I’m sure the hardships are “wearisome” to the real-life people who have to endure them, too. In their 1971 book The Book of Carpets, Reinhard G. Hubel and Katherine Watson describe the Western mania for “Oriental rugs” ignited by the 1873 Vienna World Exhibition: “Each one of these carpets, individually created through long hours of work, seemed to speak a language all its own, yet one that was common to them all… Some spirit, the spirit of its creator, had entered through the deft and skillful hand that knotted it, and this spirit seemed to give an answer to the questions that sprung up in the Western mind…How poor the ordinary machine-made carpet seemed in contrast.” When one of the women in Daughters of the Sun cuts her finger and accidentally stains the rug (she gets beaten for it), these words take on a whole new context, a context present in the film. That gorgeous rug in your foyer, in your palatial library, may be stained with the blood of the peasant woman who made it.

About 10 years ago, I corresponded briefly with Shahriar. She reached out after reading something I had written about her film. I was eager to hear what she might be working on. It’s a sad and all too familiar story. She continues to try to get projects financed. Daughters of the Sun, to this day, is her only feature film. As a film critic, much of the research I do is practical. Spell everyone’s names correctly. Make sure the dates are right. Sometimes, though, I go deeper, merely because my curiosity is piqued. I follow the breadcrumbs, and end up tripping over a goldmine. This happened while researching Daughters of the Sun. The film is dedicated to Ahmad Shamlou, one of Iran’s most celebrated poets (in the country of Rumi and Hafiz, that’s saying something). Nominated for a Nobel Prize in 1984, Shamlou’s masterwork is Ketab-e Koucheh (The Book of Alley), a 13-volume book of Iranian folklore. Born in 1925, Shamlou constantly ran afoul of the authorities, whether it was the Shah pre-Revolution or the clerics post-Revolution. He was imprisoned multiple times, and banned from publishing for years. Shahriar dedicating her film to this radical dissident is eloquent. (The censors tried to make her remove it.) I sought out Shamlou’s poetry and got sidetracked, reading it for pleasure. But when I came across “The Secret,” I almost gasped. It’s Daughters of the Sun! There’s Aman plunging her face into the well, there’s the black horse, there’s Belghies and Aman, in tears, looking at one another, not speaking. Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations. A secret was with me; I told the mountain. A secret was with me; I told the well. On the lengthy path, Alone and lonesome, I told the black horse I told the stones… With my old secret At last I arrived. I uttered no words You uttered no words; I was shedding tears You were shedding tears. Then I sealed my lips You read from my eyes…