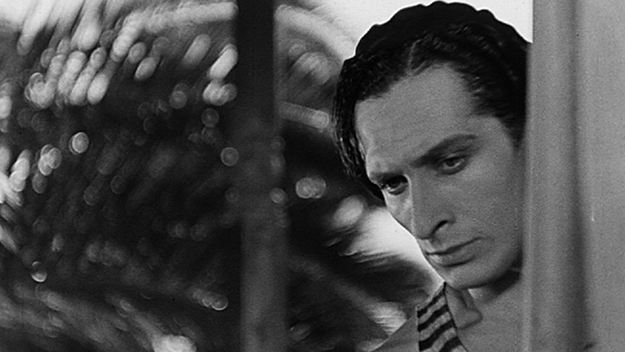

La Belle de Nuit (Louis Valray, 1934) The finding of lost films is always cause for celebration—but some films were never lost, merely forgotten, and discovering them can be just as exciting. Take the case of the only two feature films directed by Louis Valray, which were shown in the 17th edition of To Save and Project, the Museum of Modern Art’s annual series dedicated to film preservation. Introducing these new restorations, Serge Bromberg of Lobster Films recounted how he first came across a choppy, poor-quality print of Valray’s Escale (1935), and went in search of the filmmaker’s heirs as well as more of his work. It turned out that France’s Centre National du Cinéma (CNC) held the camera negative of Valray’s first feature, La Belle de Nuit (1934), but had never thought to do anything with it because the director was so obscure. Who knows how many films languish in this paradox—unknown because they haven’t been preserved, and unlikely to be preserved because they are unknown? In fact, Louis Valray was considered a minor master by some of the most knowledgeable French cineastes, Bertrand Tavernier and Pierre Rissient. His films have instant allure for lovers of 1930s French culture—like the photographs of Brassaï, they are full of couples dancing in smoky dives and streetwalkers prowling nocturnal alleys; like the poetic realist tragedies of Marcel Carné or Jean Gremillon, they bathe in the melancholy mood of harbors, ships sailing out to sea, and doomed lovers enjoying fleeting rustic idylls. Their stories dramatize the gulf between luxurious high life and seamy low life—on one side, oysters and champagne in Paris nightclubs, flower-filled theater dressing rooms, flirtatious games on the decks of ocean liners; on the other, hoodlums, drunken sailors, broken-down old floozies singing mournful chansons amid stale beer and accordions. But if their subjects are familiar, stylistically the films are startlingly original and rather odd, blending exhilaratingly fresh location shooting, lyrical images, heavy-handed melodrama, and idiosyncratic composition and editing. In La Belle de Nuit, Valray can’t resist a visual or auditory rhyme. He cuts from a dog howling to the steam whistle on a train, and from the train whistle to a steamboat’s whistle; from a pearl necklace to a roulette wheel; from a piano in a chic apartment to a player piano in a sleazy bar; from a man kissing a woman’s hand to a different man kissing the same woman’s hand. All these matching images, and the profusion of mirrors and reflections, wittily frame a story about deception. Véra Korène plays a double role as Maryse, a blonde star of the Paris theater, and Maïthé, a brunette prostitute in the raffish old town of Marseille. Maryse lives with playwright Claude Davène (Aimé Clariond), but one night while he’s away she gives in to his playboy friend Jean (Jacques Dumesnil). When he finds out, the embittered Claude becomes an aimless wanderer, until he discovers Maïthé. She’s a dead ringer for his lost love and you expect Vertigo-style obsession to ensue, but it doesn’t; instead, he enlists her in his revenge against Jean. Korène actually gives three distinct performances: as the soignée but weak-willed Maryse; the cynical, wisecracking Maïthé (who says she would “rather poke my eye out than cry over a man”); and the haughty, ice-cold siren she impersonates in order to seduce and ruin Jean. In all her forms, she is surrounded by shallow men myopically focused on their own desires and resentments. The movie is uneven, though never uninteresting. A flashback to the World War I trenches where Claude saved Jean’s life feels a bit crude and perfunctory, while a more effective flashback uses unsentimental shorthand (a bed, before and after) to show how Maïthé took the first step into prostitution. We get a more lighthearted view of the trade in a hilarious scene where one of her neighbors, a schoolteacher turned hooker, brings home a young man who is trying to distract himself from worry over his exams, and proceeds to grill him on dates from French history. There are moments when the film could be silent—like the expressive image of a newspaper bearing Maryse’s photo slowly sinking in the water off a dock, or a mute, dreamlike tracking shot of Maïthé running through the woods. But a climactic scene relies wholly on sound. The innocent young man Maïthé has come to love, oblivious to her real background, tells her how glad he is that she’s not one of “those little tarts,” and as he falls asleep with his head in her lap, she hears the sounds of her former life building to a deafening crescendo of shame.

Escale (Louis Valray, 1935) Escale opens back in the harbor of Marseille, and it delves even deeper into the sordid yet swoony low life of the red light district. Valray was born in 1896 in Toulon, another Mediterranean port city, and one of the greatest pleasures of Escale is the feeling for place: the hard glare of the sun, the men in striped singlets and canvas sneakers lounging on docks, the old town’s labyrinth of narrow alleys and leprous stone walls; the warm nights, the white-uniformed officers on leave, the steamy cave-like bars behind swinging bead curtains. Co-written by Valray and his wife Anne (who also penned the lyrics for the catchy, wistful theme song), this is another melodrama about worlds colliding. It follows two stories: that of Dario (Samson Fainsilber), a sleek gangster who smuggles illicit booze, and that of his girlfriend Eva (Colette Darfeuil), who is weary of the underworld and falls in love with Jean, an upright officer on an ocean liner (Pierre Nay, who resembles Franchot Tone both in looks and in lightweight charm). During his brief leave, they go off to his home on a tropical island for a pre-marital honeymoon, but during his long absence at sea she is sucked back into the degrading milieu of drugs, sex, and crime. (The film’s original English title is Thirteen Days of Love, but escale means a port of call, a stop on a journey, which captures the story’s unsparing vision of how paths cross and then diverge.) Valray does not repeat the stylistic signatures of La Belle de Nuit, instead using diagonal wipes to transition between scenes, with an abruptness that suits a film of dizzying contrasts. It has moments that make you cringe, particularly in the depiction of Zama (Féral Benga), Jean’s carefree, adoring African servant. It is instructive to compare this colonial form of racism with the American version bound up with slavery and Jim Crow; Zama is servile but beautiful, exotic, and ultimately a kind of innocent, avenging angel. (The Senegalese Benga would play the “Black Angel” in Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet.) It is also sobering to ponder the very different paths that the movie’s two stars would take. In a prolific career, Colette Darfeuil acted in films by Abel Gance and Henri-Georges Clouzot, and co-starred with pre-stardom Jean Gabin (Pour une Soir, 1931) and Buster Keaton during his bottom-scraping post-MGM years (Le Roi du Champs Elysees, 1934). But she compromised her reputation during the Occupation by appearing in collaborationist films, including Occult Forces (1943), a piece of conspiracy-mongering Nazi propaganda. By contrast, her co-star Samson Fainsilber was a Romanian-born Jew who had to flee France during the war—thankfully surviving and returning to work up until his death in 1983. Here he is an intense, darkly brooding and sharply chiseled screen presence; as the heavy, he combines sinister prettiness with brute physical menace, and the camera loses no chance to ogle his burnished torso. So, whatever happened to Louis Valray? His features, made independently on very low budgets, drew some admiration from critics but flopped at the box office; discouraged with cinema, he moved into radio and eventually wound up working in the chemical industry. This year’s “To Save and Project” lineup offers evidence of the breadth and diversity of independent filmmaking, from amateur home movies to the experimental works of avant-garde artists like Stan Brakhage and Ken Jacobs, to the surviving films of the McDonagh sisters, who produced four features in Australia between 1926 and 1933, taking all the major roles between them: writing, directing, producing, marketing, starring—and using their family mansion as a primary set. Their work, on the evidence of The Cheaters (1929), followed popular forms—crime, romance, melodrama—with results that are surprisingly hard to tell apart from Hollywood’s polished productions.

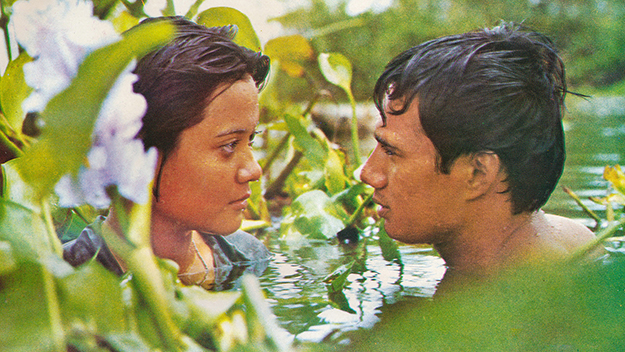

Plae Kao (The Scar) (Cherd Songsri 1977) The do-it-yourself methods and outsider sensibilities of filmmakers working independently can coexist with commercial impulses and conventional genres. At first glance, Cherd Songsri’s Plae Kao (The Scar, 1977) falls into a very different category from the unknown films of Valray or the McDonaghs. Far from forgotten or obscure in its homeland, Plae Kao was a legendary success; on its release, it became Thailand’s highest-grossing film up to that point, and it was chosen for restoration by the Thai Film Archive (Public Organization) because it was so well-beloved. Yet this blockbuster also started as an independent project: when Songsri could not find anyone to back his idea of making a period film illustrating traditional Thai life and culture, he made it with his own money, casting relative unknowns in the leads; when he failed to find a distributor for the finished film, he peddled it to cinemas himself. As it turned out, the pastoral romance appealed to a nostalgic longing for earlier times during a period of political turmoil. Songsri filled it with crowd-pleasing elements: heartstring-tugging songs, bloody fights, picturesque landscapes captured in widescreen and color, and two delectably beautiful young actors as the star-crossed lovers Kwan (Sorapong Chatree) and Riam (Nantana Ngaokrachang). Set in a rural village in 1936, the film was based on a novel by Mai Muengderm, but feels rooted in legend and folklore, filled with traditional songs, village festivals, and a classic story of feuding families. Midway through, a visiting theater company bedecked in ornamental costumes performs a stylized, over-the-top melodrama that echoes and is intercut with the “real” story, underscoring the self-awareness of the film’s own exaggerated emotions and plot twists. (Similarly, La Belle de Nuit opens with a histrionic confrontation and murder that proves to be the curtain scene of a play, literally setting the stage for the mannered posturing and scheming of the movie’s characters.) The patterns, and the appeal, of melodrama are universal, but this movie’s flavor and fascination come from the specificity of place—the way it immerses us in the almost amphibious life these villagers lead amid rivers and rice paddies, thatched huts and the tangled roots of banyan trees.

Plae Kao (The Scar) (Cherd Songsri 1977) At times, the lush beauty tips over into cloying, saccharine prettiness—especially in musical interludes that recall gauzily generic karaoke videos. But the beauty remains anchored by vivid physicality—the squish of liquid mud and weight of sticky heat—and by the effortless charisma of Sorapong Chatree. In a performance that ranges from exuberant playfulness to operatic anguish, he is naturally, nakedly emotional, even when the dialogue—at least in translated subtitles—is formal or stilted. (Like Fainsilber in Escale, the usually shirtless Chatree is unabashedly presented as a desirable object, far more so than his pretty but modestly retiring co-star Ngaokrachang.) Plae Kao cannot be accused of simply idealizing traditional Thai society and values. Idyllic scenes of the lovers’ combative courtship and innocent romance—racing their water buffaloes across green paddies, swimming and having mud-fights, kissing submerged to their necks among water lilies—give way to episodes exposing the patriarchy at its ugliest. When Riam’s brutish, tyrannical father finds out she loves Kwan, he chains her up and then drags her off to Bangkok to sell her to a wealthy woman, and he savagely beats her mother when she tries to intervene. These scenes are raw and upsetting—especially the mother’s misery as she laments, “My child, I can’t help you”—because they are all too believable, not the stuff of melodramatic contrivance but of the common cruelty of power. Towards the end, the film takes an unexpected, perhaps culturally-specific turn, as the parent-child bonds between Riam and her mother, Kwan and his father, almost displace the central romance. In celebrating what has been found and preserved, rediscovered and refurbished, “To Save and Project” also calls attention to how much remains lost or impossible to see. The Cheaters was preceded by a tantalizing fragment (all that survives) of Paulette McDonagh’s Those Who Love (1926), which opens with a woman in a harlequin-patterned bathing suit doing the Charleston on a beach, and in its brief four minutes shows a couple trysting on the industrial docks of Sydney and a brawl in a seedy dive that would almost pass muster in a Louis Valray film. Here’s hoping that one turns up some day. Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy, and has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere. Phantom Light is her regular column for Film Comment.