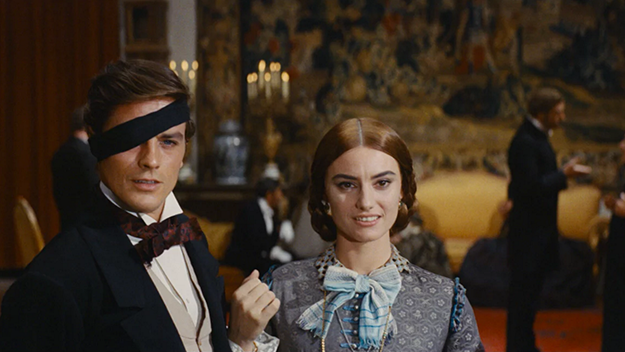

Heaven Can Wait KENT JONES: It’s your first time in the new Alice Tully Hall. MARTIN SCORSESE: It’s my first time in the new Alice Tully, because the other [Film Foundation] events have been at the Walter Reade for the past few years. KJ: We were just talking backstage and I realized that Heaven Can Wait and Brooklyn, a Fox Searchlight picture, are both on 35mm. I wanted to start with the beginning, which is when you first realized the need for restoration and preservation actually had to exist. It was at a screening in L.A., right? MS: Yes. It was at LACMA, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. I always imagined the room to be this big, but it was much smaller. They would have these wonderful programs back in the early Seventies, and one of the big ones was 20th Century Fox. They had restored a number of films—Sunrise, Blood Money, Seventh Heaven, the Rowland Brown pictures, about four or five of them. And they showed all the prints from the Fox vaults at the program. KJ: So it all begins with Fox. MS: Yes. I saw this film [Heaven Can Wait] in the original studio nitrate print. If you see nitrate on a big screen, there is a difference from “safety film.” This goes off the subject a bit, but I was talking about projecting a certain classic film off of a Blu-ray on a big screen for young people who are 13 or 14 years old. The impact, if it has any, is still the same, but it’s not a film experience. It’s a different kind of experience, and I think it’s akin to the difference between nitrate film and the celluloid that we’ve known for the past 50 years or so. So we’d go on weekends—Jay Cox was with me, Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma, a number of people—and they were showing everything from the silent films to the Fifties ’Scope pictures. And the black-and-white nitrate was amazing. This was right before I made Mean Streets in 1973. Around the same time I was living in Los Angeles, trying to see classic films, and we really couldn’t find good copies. If we were at a studio—Steven was at Universal, I was working for a while as an editor at Warner Brothers—and I’d ask to screen a film, they’d show me a studio print or something. But we were aware it was difficult to see complete films, films that weren’t scratched, or where the color wasn’t messed up.

Niagara We had seen Wilson [44] in 35mm Technicolor nitrate, The Black Swan [42], Blood and Sand [41], all these extraordinary uses of Technicolor from the late Thirties as part of the LACMA program. Wings of the Morning [37], the first British one… We didn’t know the full extent of it until one of the nights at LACMA, they were showing Niagara and The Seven Year Itch. So we sit through Niagara, which is a beautiful Technicolor film noir. And then there was a break, and before the second film begins, Ron Haver—who was amazing and pulled this all together, this show—comes out and says that the print of The Seven Year Itch from the studio is faded. This is 1972, or ’71. The Seven Year Itch was made in ’55. What made this so dramatic is that Niagara was made a couple of years before in ’53. When Fox got their first anamorphic lenses, every film, black and white or in color, they all had to be made in ‘Scope. And the color system was changed from a three-strip to a Monopack. So Ron Haver comes out, tells the audience that it’s a little faded, and everybody groaned. We had missed some other ’Scope films during the week that didn’t live up to their original glory, so to speak, and apparently the audience was quite aware of this. Then Ron said, “Listen. What’s going to happen is that we’re going to put a filter—” and people started yelling “No, no! Don’t put the filter back on! It goes out of focus! Please!” They were trying to correct the color by putting gels in front of the lens that would melt and make it go out of focus. So I said: “What the hell is going on?” The film starts, and it’s pink and blue. The whole thing! Beautiful stereophonic sound. Whatever you may think of Billy Wilder’s film, the Axelrod thing, the color, high Fifties, we’re talking an iconic film…We were so disappointed—our eyes were treated to this extraordinary Technicolor of Niagara and the films that had preceded it, and this was like falling off a cliff. It was such a shock. We began to realize that everything since the Monopack was like this. This was the studio print. How did it get like this? It’s only been a few years! You couldn’t see the features of the actors anymore. You could, but it isn’t the same as seeing their faces in the lighting style of the Classical Hollywood era, either black and white or color. You couldn’t see what you were supposed to see. On top of that, you’re dealing with icons of cinema: Marilyn Monroe, a film that— KJ: —Tom Ewell. MS: Well, Tom Ewell no, but this is American theater, translated to screen. You’re missing the narrative, you’re missing the performance. Something is wrong with the image. So then they put the gels on, and it started to get soft, and people started to stamp their feet and get really mad, and that’s when we said “Let’s get out of here.” And we walked out. There were about five of us, and we were like: “What the hell? How can this be?” We’d seen bad copies of films on television, but not in a museum, not such a dramatic change. I saw House of Bamboo [55] at the studio: terrific stereophonic sound but the image was distanced and aged in a way. Long story, it goes on like this because we tried to find prints of films by 1975, ’76, and—oh, even The Leopard [63]! It was difficult to get a print to see that was in good condition of this film. The American version was two and a half hours or so, but even that was gone, so we got a 16mm print, but that was magenta.

The Leopard I remember when we inquired further, Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma too, they said that we can’t keep all these prints around. I’m not talking about the studio prints, but at that point we realized the future of what had been created up until 1950 or 1960, that if nobody was made aware of it, it really came down to people going into the vaults and going through the cans. And that’s hard to do, because the people who are employed that way, they’re there to make sure that if they’re sent down there, they can find something—and that’s about it. But when they open these cans and look at them, for example, there was no system. Also around that time, in 1970, MGM went under and the films went somewhere else. Paramount had sold all of their pre-1948 films to Universal before video came out, thinking that there were no more legs in them, that they couldn’t make any money from them. There was an idea that film libraries were something that you had to get rid of. There were stories of negatives being burnt and thrown away. KJ: And negatives that had been run into the ground, that had been used again and again. MS: Particularly for very famous films. They began making more prints off of the original negative, over and over again, because there was a demand for it, and that disintegrated the negative. Rope [48] was that way, but it’s been restored by Fox. A lot of the prints were often original neg on that. But it was one of those things we began to realize: that the studios were in flux, that things were changing. There was no time for people to think what films are, what they were, what they can be, and what they are to a new generation. We got a bad rap in a way because we were young kids in our late twenties or so, and they thought we had to go to school to learn films. Some of the older guys working out there would say: “We didn’t have to school to learn how to make a film.” I’d say: “No, it’s not that you have to go to school to make a film. We’re very lucky to be involved with certain professors.” We got our hands on some equipment—but that’s New York. There was very little independent filmmaking in New York. Not enough, I should say. There was an impact—Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke, all the avant-garde cinema. There was an impact. But one wasn’t fed into the industry if you wanted to go that way. And I knew that narrative cinema was my thing. KJ: You guys were the upstarts. MS: Yeah, we were. They kept saying: “Well, what do you want to see these films for?” And we kept pushing them for making new prints. And the man who came in and made the biggest buyout was Ted Turner, getting all those films from Warner Brothers. KJ: Who everybody thought was a villain at first because of colorization. MS: Yes. Well, there was a battle there with colorization because there was that line: “Last time I looked, I owned it, and I’m going to do what I’m going to do.” And then it was a conflict about the value of the work of art. How can it be a work of art if it’s a commercial thing? Hmm. [Pauses] Let’s think about that. No! It means a lot to people. It’s inspired artists, novelists, poets, and painters, not just people who simply enjoy making narrative on film. It was really a mindset that had to be changed.

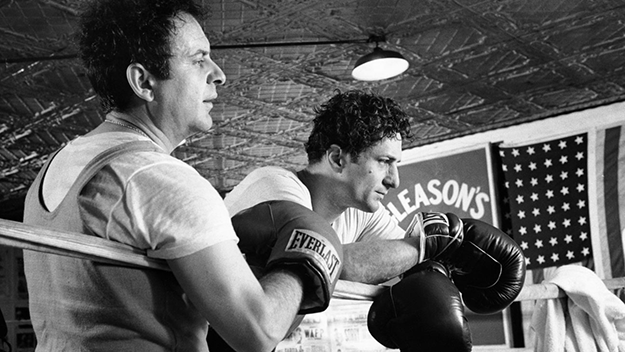

Raging Bull By 1979, I had really had it, and I couldn’t find anything that was in any good shape, and I decided to make Raging Bull in black and white. Also because there were about four other boxing films coming out that year: The Main Event, Rocky 2, and Matilda, the boxing kangaroo. [Audience erupts in laughter] Well, the Australians were a big deal with Mad Max… So what’s gonna be the difference? You’ve got a nice comedy, you got the Rocky thing, you got a kangaroo. But the red gloves? What is that? We’re gonna be killed! Let’s just do it black and white. The studio was originally not for it, but we eventually got that done. I was so angry about [color stock fading], the only thing I could do was to send an angry letter out about the fact that now every film has to be made in film at the studios, and if everything has to be made in color, that’s when the color gets cheaper. [As a director] you spend all that time designing in color—because whether it’s shades of browns and grays, you still have to design it, and then time it. It means something, the way you see things, and that’s just when the color’s not going to last. Just when you have to do it, that’s when it’s going to be bad. The time where it did last, which was the old Technicolor, it was considered mainly for musicals and comedies and Westerns, that sort of thing. I said that you can’t work when one of your major tools is being destroyed, and we have to do something to get a better color stock. So I attacked Eastman Kodak and sent out letters around the world to the filmmakers asking them to sign this petition to get a stronger, stable printing stock. There were many signatures, everyone from Ingmar Bergman to Kenneth Anger. Everyone signed it except Bob Altman. Bob Altman said that it’s not the film manufacturer, it’s the distributor. And I think he’s right. Afterward he became part of The Film Foundation, and he understood. But it was okay—we had to go after something, and I brought this idea of the color fading. Then I began to realize, if that’s what you think about our culture, then there’s nothing in the culture. It’s a culture that you use up and throw away. You don’t care about it. If everybody’s walking around thinking that film changed their life, that a book changed their life, thinking that it’s going to be there all the time, to keep a continuity with the younger generations of this thing… If you think art is important at all, whether it’s commercial art or not, it seems to me it’s art. Maybe some are better than others. If it’s good, bad, or indifferent. It’s still art and we all know it’s very, very hard to even make a bad film. KJ: Yeah… [Audience laughs] MS: Very hard. But if it comes out really bad, that’s why. With all of that effort and all of that love that was put into something—in most cases—and it means something to people, if the idea was just to show it only for a little while and then maybe show it cut up on TV, and then that’s it, what are we talking about in our culture? So I put together a program that I took around the world when we opened up Raging Bull and went on tour with it. We started with the trailers in color, one of them being Invaders from Mars [53], William Cameron Menzies’ film, very low-budget super Cinecolor film. And they were all laughing in the audience and I said: “What are you all laughing at? This is Close Encounters.” Those who know about the film I’m talking about, you know it’s the great William Cameron Menzies. There’s a new book coming out about him finally. You should see it and read it. Menzies is so important in production design.

Invaders from Mars This is one of the films that certain people saw at a certain age and it’s your cinema now—this is where it came from. So if you say “Invaders from Mars, who wants to keep it? Let it rot”? It’d change the industry! Funny, you know? Then I went into films by [Franz] Boas, North Native American tribal ritual dances, which were done in 1915, 1920. And then I showed a clip of a rocket going to the moon, NASA footage, I think. You see the rocket going in this glorious magenta. You made it to the moon, but the film was gone. It’s really interesting. What kind of thinking is this? And it was really a level of consciousness that we tried to change. It was hard because Eastman Kodak said that we had to talk and they said, you know, this is not our thing. There is a stable stock: it costs a penny more a foot. And the studios at that time didn’t want to pay that. It’s not like now. If you’re going to send, what, 10,000 prints out or something, 4,000 prints, it’s a lot of money. But no one ever thought of it, to pay that extra penny a foot for the more stable stock. But that changed a lot. Everything changed, I think, by 1983-84. They made that stock available at no extra cost and that stock was called LPP at the time, and then it got better and it got much better and it continues to. The point is that the film itself is no longer going to be around much longer. Yet we all know that the only stable element for preservation of film, even when you go through it digitally and you do your whole digital 4K, 6K, whatever it is. The only stable thing ultimately—you make separation masters and everything onto black and white— [is] celluloid, which supposedly lasts about a hundred years, 70 to 100 years. KJ: A round of applause for celluloid.

Wings of the Morning MS: George Lucas was with me the other day, and we were talking and he says: “Yeah, it’ll last 10 years.” “Oh come on George, I’m telling you that celluloid…” He said: “If you’re doing a DI, you’re making a digital film.” I said: “I know, but still…” So we’re using film and digital at times. KJ: The Film Foundation was formed in 1990, and over 600 films have been restored. MS: The thing about The Film Foundation came out about the late 1980s… I tried to find films and restore the negatives by making new prints, and I would get permission from the studios to make new prints. The one that was the hardest was Pursued [47], Raoul Walsh’s Freudian Western. Once we got that, they couldn’t make a print of the original negative. And so Bob Rosen at UCLA at the time said: “Why don’t you take whatever color you guys have at this point and put it together and bring it to the studios and explain to them and see if you can create a little group.” And so with Mike Ovitz at CAA, we put together The Film Foundation. Sydney Pollack joined up, and Steven of course, and Lucas and Coppola. KJ: And Altman. MS: And then Altman came in, Robert Redford… KJ: Clint Eastwood… MS: Yeah. So what I did was while I was editing Goodfellas, I went through these books they call The MGM Story and The Warner Brothers Story, and they had every film that the studios made. And I tried to put them in order of, not importance, but a kind of necessity, whether it was a film I liked, I thought was overlooked and/or whether it’s a film that was Warner Brothers’ first two-strip Technicolor film. So I tried to put them in A, B, and C categories, and then I would get meetings with the heads of the studios with these books. They would let me in because I’d just done Goodfellas. I think it was one of those things where, you know: “He did Goodfellas and people like it but just… he has this thing. Just let him do his thing. Let him come in. Don’t make any kind of any fast moves.” You know what I’m saying? That kind of stuff. I remember it was Mickey Schulhof at Sony, because George Lucas went to the head of Sony at the time, Mr. Morita, and Mr. Morita said: “Michael Schulhof is the man, see him.” So we got a meeting with him and when I gave him the book, he looked through it and he said: “You did this?” And I think what was very sweet about it is that he realized: “Yeah, they love these things. They love it.” He said, “You really went through all that?” It was every one of them. And then there was Bob Daly and Terry Semel, and Bob turning around to Warner Brothers and saying: “The problem is 20 years from now. What’s going to happen when we start doing the same thing?” That was the key to it. How is this going? Once you start with your photochemical restorations—digital was not around that clear at the time—but once you start that way, how is it going to change and how is it going to be? How is it going to be cared for and preserved?

For Whom the Bell Tolls The whole key of The Film Foundation was to unite the archives with the studios because, as I used to say, the studio was not only in production and distribution of a film, but it was production, distribution, and conservation. This art belongs to everyone. I said, you’re the custodians. That’s the idea. You have the great responsibility for preserving this work. Prior to that, the archives, from what I experienced, what I saw, were suspect, because they would find prints in garbage pails or whatever. But those films technically belonged to the studio, not the archives. And so in the worst-case scenario, they’re considered thieves. And it turns out—I remember it was the main head executive there at Universal years ago, when UCLA somehow restored For Whom the Bell Tolls from Universal Pictures, and Technicolor wanted to screen it at one of the theaters at UCLA, and they were stopped by the heads of the studio because they said: “It’s our picture. What are they doing? We own it.” But then they got involved too. Steven Spielberg went to Lew Wasserman and talked to him about it to try to change the thinking. That’s a very different kind of thinking, you know. And at the same time, video started, and it was enormous. Then they realized that there’s no such thing [as] “an old film is just a film,” but, as Peter Bogdanovich said, “there’s also film that you’ve never seen.” That’s all. Kids know the difference to a certain extent with black and white, and even then if they show them in the right circumstances, it doesn’t matter after a few minutes. Anyway, that’s the general idea. Margaret Bodde and Jennifer Ahn… KJ: Give them a round of applause. MS: They were raising a lot of funding, an extraordinary amount. And one of the key things was that at the time we were told: “Don’t go into funding because it’s going to hurt possible funding for the archives from other places.” But I said, no, I think it’s something we could override if there was any kind of contention amongst the archives. At that time there were five, and now it’s seven. “If there’s any difficulty, we can override that. We’re talking about cinema. We’re talking about the film itself.” KJ: Yeah. I think that that’s been overcome. Also, consciousness of film preservation has changed now. You mentioned something before, as we close, because we’re getting the high sign here— MS: I’m sorry. It’s a long story. It’s 25 years, as it turns out. KJ: I just want to close by saying that you know we’re celebrating the two anniversaries and the Fox anniversary, [and] just to say that you mentioned the idea of the studios being great custodians. This is the Fox story. MS: Amazing. Every film, everything on the shelves. And all of that talk of the faded prints, forget it. This is the best. It’s amazing. I never thought I’d experience it, honestly. KJ: I know, and that’s where it started. Thanks, Marty. MS: Thank you, everybody.