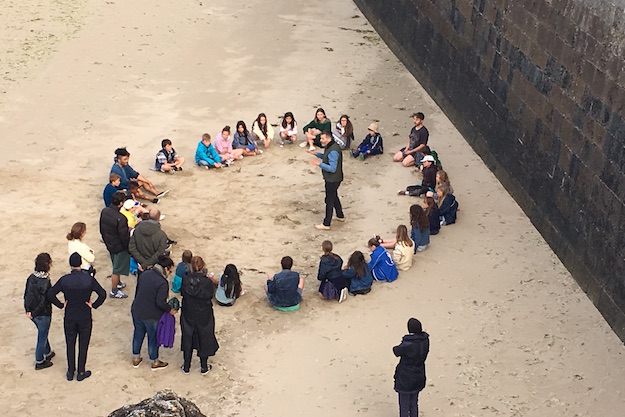

Sorry Angel In June 2017, I traveled to Binic, France, in northern Brittany, to visit the set of Christophe Honoré’s latest film, Sorry Angel. Honoré thinks fast on his feet, and to see him work in person is to engage with a quick-witted, well-read, and devilishly funny artist. Because of this, his direction is never stale, and his fresh ideas are prompted by collaborations with his cast and crew. On the other hand (perhaps ironically) the sharpness that underscores his impromptu tendencies reveals an ascetic intellectualism and precise eye for cinematic detail. It is within this paradox that we discover an “Honoré” film. Sorry Angel is situated squarely in the middle of Honoré’s recent multimedia triptych. The first work in this project is the novel Ton père (2017); the second, the film Sorry Angel (Plaire, Aimer, Courir Vite); and the final installment, the stage play Les Idoles. The three projects are representative of the key mediums in which Honoré traditionally works; moreover, in laying these works side by side, the director foregrounds his position as a French gay cinéaste who, like the filmmakers and writers who came before him (his homosexual “idols”), envisages the cinematic as a multimediated encounter infused by homosexual desire. Sorry Angel, which has its North American premiere this Sunday in the 56th New York Film Festival, tells the story of Arthur (Vincent Lacoste), a university student in Rennes who falls in love with an older, HIV-positive writer from Paris, Jacques (Pierre Deladonchamps). Arthur is 22 while Jacques is 35. The director’s commentary brings into sharp relief a cinematic vision through which homosexual desire is transformed during a complex historical moment when comprehending AIDS was, at best, incomprehensible. On my visit to the set in Binic, two moments were suggestive of Honoré’s at once off-the-cuff, fast-thinking direction and detailed attention to his filmmaking. In the first, I was struck by a shot made following a take with the character Nadine (Adèle Wismes). The tracking shot follows her along a sea wall as she heads into the next sequence, in which Arthur guides children in the game of “Pan! Pan! Lapin!” Several takes were made as the actor and director refined her movements and facial expressions. Once completed, Honoré had his cinematographer, Rémy Chevrin, duplicate the tracking shot without the actress. Later, I asked him why he decided to make the additional footage. Was this predetermined in advance, or did it occur to him while making the first shot for the film? He responded with a smile: “You have to experiment.” In the second on-set discovery, Honoré’s pre-production instructions to Lacoste highlights the director’s particular way he works with his actors. Lacoste (born the year in which the film’s narrative takes place) told me that Honoré gave him homework so as to get a sense of the early 1990s. He instructed Lacoste to watch My Own Private Idaho, Crash, and Happy Together. Additionally, Honoré gave him two bottles of perfume from the era (Cacharel pour Hommes and Vétiver pour Pierre). In effect, Honoré offered the young actor both the material and abstract tools to evoke “Arthur.” Honoré set the stage, in other words, for a sensual memory not yet lived. My interview with Honoré was conducted this past summer on Bastille Day (July 14) at his atelier-home studio just north of Paris. The translation is by Pierre-Alexandre Moreau; French transcription by Guillaume Seeleuthner.

Christophe Honoré on the set of Sorry Angel. Courtesy of David A. Gerstner You’ve described your films as works made for “good company.” That is to say, they are not for everyone. For whom is Sorry Angel made? It is increasingly difficult for me not to ask myself this question about who the spectator is for my films. When I started making movies, I didn’t care. I was caught up in the excitement of making cinema. I was responding to all the films I had seen, with my own films. I was writing myself into the larger cinephiliac concert! Today, I’ve lost that spirit, though not from a loss of desire for the cinema. What has changed is the environment for the production and distribution of films. The discourse of cinema is in decline in France. We are constantly reminded with doomsday scenarios that French auteur cinema no longer interests anyone. Directors are told they have to go back to the big subjects, the genre films. Apparently, my way of making films in the first person—a mode of filmmaking that derives from literature—no longer resonates with the audience. So, to fight against this insistence by the film industry that the director must make films for everyone, I came to the conclusion that I can speak to only a few. In other words, I’ve had to come to terms with the fact that I make films with the idea of an intimate spectator. My films are for the viewer with whom I share the memory of the movies I’ve seen, the books I’ve read. It’s like a secret society. It’s an assembly of people united in the love of the humanities. You might think that the intimate spectator is a sign of elitism, or snobbery. But I don’t think so. On the contrary, it’s modesty. In addressing myself to some, I hope to reach the largest number—but the largest number of some, not everyone. You stated while making Sorry Angel that “one is always in search of lost time in the cinema—especially French cinema. In the case of this film, it is without doubt that some nostalgia is imprinted into the film.” At the same time, you recognized that you were making a movie in the present, and that every day filming demands that you live in the now. Given this tension between your personal memories and rewriting them into a film, what do you wish contemporary spectators to experience when they see your films? With Sorry Angel, this tension is found at its very heart. While writing the screenplay, I relied on memory more than imagination to establish the film’s narrative. This is why I decided to situate the story in Rennes during the 1990s, when I was there as a university student. Nevertheless, fiction is not absent from the film because I invent a love story between a student from Rennes and a Parisian writer with AIDS. At the very heart of this scenario is sincerity and truth. I tried to get close to a feeling of youth, to be close to this guy in his early twenties for whom I have a memory. At the same time, I offer him a fiction, a story he did not live—which is something I suffer from today. This is where the “today” appears—that is, if I embarked on this film because I’m inconsolable today as a filmmaker and writer who was never able to cross paths with the idols from my youth. I was never able to meet the homosexual artists who were especially important to me during the ’90s—in literature, Hervé Guibert [1955-91] and Bernard-Marie Koltès [1948-89]; in the cinema, Jacques Demy [1931-90], Serge Daney [1944-92], or even Cyril Collard [1957-93]. I believe that when you write a book or make a movie, the people you would like to touch first and foremost are the people who made you want to write books or make cinema. I would have liked for my first film to be at a film festival where I came across Jacques Demy and he put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Welcome little guy!” I don’t think of this as being an heir to their work. It’s more like a way of paying my debt to them. So, it’s true with Sorry Angel. When you talk about the tension between today and the staging of the nostalgia of my youth, I feel it mainly through this loss. Sorry Angel is an incomplete transmission. This is the loss I have today, this inconsolable feeling. We spoke earlier of “good company.” These artists I never encountered are just that.

Sorry Angel Is the “good company,” then, made up by ghosts? When we work, “good company” is always imaginary. I remember when you and I talked about this last time I was in New York. We talked about the “good company” in the salons, like those of Racine—authors from the 17th century who wrote for a small coterie who were all known to one another. They wrote with the idea that they knew exactly who they wrote for, and who attended their plays. It was a very closed world. Today, a salon like this doesn’t exist in France, and especially for the cinema. The filmmaker has no direct link with a salon, or a privileged audience that participates with their work. So, this “room” for me is still imaginary and, as you say, it is composed only of ghosts. It’s true. I write mainly for the dead, or I make films for the dead. And so Sorry Angel is a transmission not completed. I tell it through the story of a transmission that seems to be between this writer and this young student. But the transmission plays more as a lover’s discourse. We see that it is mainly sentimental, even when they exchange books and ideas on literature. In the film, the relationship to today is brought home in the last sequence when we see Arthur waiting for a phone call that will never come. The film makes note here of the impossible conversation. It echoes my anticipation with a conversation I will never have with people who gave me both the desire and the stubbornness to say as a 20-year-old: “I want to do cinema! I want to write books! And it will happen!” Now I’m at an age when I inevitably meet young people who are around 20, who have seen Love Songs [2007], and who want to make cinema because my film made them want to. Perhaps Sorry Angel holds my place in the cinema world as a link between these young cinéastes and the elders who have passed away from AIDS. I suppose, though, I want to convey—although I really do not like the phrase, “to convey to the audience”—the idea of an incomplete story. Incompleteness is something important in my work. Prior to Sorry Angel, in which AIDS holds a central place, you made several other films that deal directly or indirectly with AIDS, homosexuality, and pansexuality: Close to Leo [2002], Love Songs, Man at Bath [2010], Metamorphoses [2014], and so on. In France, many films and TV series have recently taken on a recollection of gay and lesbian history, some placing an emphasis on HIV and ACT UP Paris, like Robin Campillo’s BPM (Beats Per Minute), while others such as Philippe Faucon’s TV series Fiertés (“Proud”) addresses the post-1968 gay-liberation movement and the legal victories for gay marriage and adoption. In some ways, these films are similar to Sorry Angel insofar as they look back at the same period when gay culture was besieged by AIDS. Why do you find it important to now take up this narrative about sexuality, love, and AIDS in the 1990s? It’s a question of delay. I think for the people of my generation—those born in or around 1970 who had their first sexual experiences during the mid-to-late-’80s—and who escaped AIDS, though nevertheless lived with it completely. That is to say, even if we were fortunate not to have been infected, AIDS was an absolute part of our lives. We obviously saw friends with their sick lovers, and we had friends who died. At the same time, I don’t think that we were in a position to speak as witnesses. For a long time, I thought that, morally, I was not the best person to talk about these things. It took 20 years to authorize myself as an artist to speak up and to build a narrative around it. It was such a trauma that it was difficult to ultimately confront. Despite all this, my first children’s book that I wrote in 1995—Tout contre Léo—told the story of a family in Brittany, with four brothers, one of whom was sick with AIDS. But at the time when I wrote the book I really wondered about my legitimacy to tell this story. After I made the film version of Léo, I didn’t really address AIDS again until Beloved [2011] in which the HIV-positive Henderson [Paul Schneider] lives with HIV during the end of the 1990s when treatment had much improved. I remember very well saying that it’s good to show a character with AIDS whose destiny is not tragic. He does not die. In fact, the character’s difficulties are focused on love and everyday life. It took nearly 25 years, and 10 films, before I dared face this period of the 1990s. And it’s why Sorry Angel is part of a larger project for me. It is the second work of a triptych in which the first part is the novel Ton père. Here, in the first person, a homosexual father tries to write about his life today in the wake of those authors who came before him and wrote about AIDS. The third part of the triptych is a play, The Idols, which just premiered at the Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne in Switzerland [on September 13]. In this work, I bring to life those artists who died from AIDS and who have played an important role in my work. I knew that once I began work on this project I was going to spend two to three years of my life carving out my position—my nature as a gay artist we might say—so that I could speak from the first person about the 1990s, about AIDS, and, taken together, about the loss that I still feel today about those artists decimated by the disease.

Christophe Honoré on the set of Sorry Angel. Courtesy of David A. Gerstner What is the difference between Sorry Angel and BPM (Beats Per Minute)? I wrote and shot Sorry Angel at the same time that Robin developed his project. I didn’t even see his film before editing mine. In any case, I never said to myself, “Ah! Robin Campillo has the idea to make a film on the ’90s and AIDS, I must do mine!” I’m not surprised that we both had the same idea. I spoke a little to François Ozon, who called me after seeing Sorry Angel and said, “Now, I must absolutely make my film on the ’90s. You gave me the courage to do it.” I say, so much the better! I cannot wait to see François’s film. As a homosexual filmmaker, I would like François to tell me something about the ’90s and AIDS because it’s very hard to talk about our youth in the ’90s and avoid AIDS. It’s not possible to say, “We can’t talk about AIDS because other films have done it.” From the moment we make films that are part of a powerful historical context—and I believe that AIDS is part of a historical context that has not been appropriately accounted for—we run the risk of minimizing a generation’s trauma, and not only for homosexuals. Of course, movies that reconstruct a historical moment always run up against the danger of nostalgia. But it annoys me a little that we forget that a movie is a movie. A film cannot say it all. When I was in Cannes I met journalists who asked me, “So, after BPM, won’t we be bored by another AIDS film?” I told them, “No! There are plenty of films to make about AIDS today. I haven’t seen, for instance, the movie that tells me about AIDS in Africa today.” It’s not my place to do it, and I think an African filmmaker would be much better at doing it than me. I mean, so many other movies can be made about AIDS. We can’t put the weight of the AIDS film on a single movie—whether it’s BPM or my film. The character of Nadine in Sorry Angel is key for a number of reasons. Like many of the women in your films she finds herself in the crosshairs of men’s desire—gay or straight. What is often striking about your presentation of women is that their struggle to discover who they are and what their desires are are sometimes critiqued as unsympathetic or powerless. Would you talk about Nadine, and what you see as her role in the film? For Arthur, Nadine is an ally. What interested me about her character—and it’s an area I’ve explored elsewhere with the relationship between Véra [Chiara Mastroianni] and Henderson in Beloved, and in my first feature, 17 fois Cécile Cassard [2002], with Béatrice Dalle and Romain Duris—was to ask myself: what story can I tell about the relationship between gay men and women? It’s an essential question in gay men’s lives. It’s pretty classic to have a story about a friendship between a woman and a gay man. But what other story might we tell that goes beyond a simple friendship? This question is important to me because it is what I live—that is, a gay man can have children with women and then live as a gay father. In Sorry Angel Jacques has a child with Isabelle [Sophie Letourneur], which creates a link, a story of friendship between the two. Arthur’s character lives in the moment, but Nadine does not have access to his world. Two scenes with Arthur and Nadine are important here. In the first, we learn that Nadine is in love with Arthur but that he is not in love with her. Sorry Angel is not a love story, even though Arthur and Nadine live together. Instead, it’s a story about a lie that is so important for Arthur to keep about his sexuality. And because of this lie nothing serious can happen between them. In the second scene that takes place in the tent, Arthur finally tells Nadine [about his sexual desire and his relationship with Jacques]. Suddenly, they share a stronger bond because the truth is revealed. Yes, Nadine remains confused by her love for Arthur. And, for me, this scene carries great sadness because it’s about personal matters. What I mean is, I remember when I was 18 or 20 years old and having a love affair with a young woman, there was always a moment when I said to myself, “I’m making this person miserable.” It’s an unbearably vain thing to say, but it’s this idea of trying to avoid making someone unhappy, a person for whom one can experience love but not desire. In a way, your question is troubling for me. I find it too simple to say, “Obviously, gay directors represent female characters in their film who are always invisible.” It’s not true. Sorry Angel is a film with the ambitions to make a table of manners. Not a little unlike Balzac’s paintings of manners. Can you explain a bit more about what you mean by a “table of manners” in relationship to the film narrative and representation? In Sorry Angel I represent very different homosexuals during the ’90s at the time of AIDS. There is the student, Arthur; there is the writer with AIDS, Jacques; there is the journalist-friend, Mathieu (Denis Podalydès); there is the former lover dying from AIDS, Marco (Thomas Gonzalez); there is also Jean-Marie the gigolo (Quentin Thébault); and, there is the hitchhiker (Luca Malinowski). Sorry Angel is a kind of galaxy of homosexual characters who do not necessarily look like each other and offer a kind of panorama, a comedy of morals. And, then, there are two female characters, Nadine and Isabelle, the mother of Jacques’s son LouLou. The film’s characters are echoes of one another’s stories: Jacques and Arthur are a bit of the same character at different ages, while Nadine and Isabelle share similar histories. Both women, in other words, have a particular story with a gay man. For Nadine, it’s a love story of youth and for Isabelle, it’s the story of having a child with a gay man. And the way these women handle these situations takes place with a certain freedom on their part. They live. They make choices. I do not feel they are made invisible, or dismissed in any way.

Sorry Angel Some critics would like me to have had the women in the film occupy a greater place at this “table of manners.” But, as a filmmaker, I can’t address all of these questions in one story. For example, I was working with a dramaturge on The Idols, and he said to me, “You know, you have to include lesbians in your play because it’s important to show lesbians’ role in the fight for the fight against AIDS.” I don’t disagree with what he said, but that’s not my subject. Heterosexual artists are not told that they must represent the world in its entirety. But we, on the pretext that we belong to a minority, should represent all the parts of this LGBTQ minority? I think these questions are dangerous because afterward you end up writing books or making movies with the idea that you have to please everyone. This is the kind of talk we hear from producers when financing films, or when French television commissioners must decide whether or not to spend money on a program based on how certain characters are represented. I’m not a sociologist and I’m not a historian. I’m just trying to be sincere. Your filmmaking demonstrates a great amount of precision in its mise en scène / décor, camera movement, and performance. At the same time, you appear willing to experiment on the set. Do the final cuts of your films ultimately look like what you anticipated on the first day of shooting? Do you storyboard? Never. Fortunately, the film I have in mind is never the film I discover in the editing room. I spend a lot of energy at the time of shooting. I admire that other filmmakers prepare so well before their shoot. But I am not at all a filmmaker like the masters. I hate to execute plans. For me, filming is really in the moment. It’s where a truth happens that wasn’t foreseen. It’s the truths brought out by the actors, by the weather, by the camera movement that didn’t work. I am always very attentive to the fact that the film reinvents itself completely during filming. In fact, when Louis Garrel abandoned Sorry Angel, it provided the perfect opportunity for the film to entirely reinvent itself. [After promotion for the film’s production was announced in the media in March 2017, Garrel had second thoughts about the project. Deladonchamps accepted the role in June 2017.] How would you describe your overall approach to filmmaking—from preproduction to postproduction? I am not a director who is absent from any phase of the filmmaking. I am always present at all locations. This way of filmmaking belongs to European cinema insofar as the filmmaker is really the one who chooses everything: from the color of underwear to the apartment location. It inevitably requires a permanent presence and attention of the director during preparation and then at the time of assembly. I’m not of the mindset to leave a project during its different stages. Blue permeates the film’s palette. What were your thoughts in using this color to tell the story in Sorry Angel? It is a historical film. We had to ask questions about the reconstruction of the 1990s. From an architectural point of view, I find the filmmaking from the period to be disappointing. We say, for example, “I’m going to make a film that takes place in 1970s,” and we immediately imagine the era’s scenery. The same can be said of the 1980s but not the ’90s. There is no common language from the period. It’s really a time where one has the impression that AIDS erased everything, destroyed everything… Along with my collaborators—art director Stéphane Taillasson, DP Rémy Chevrin, and costume designer Pascalaline Chavanne—I planned to shoot Sorry Angel as a winter film in summer. It was an idea that a winter film evokes cold—the blue hues—but it had to be shot with summer light, colors that are rather golden and warm. Whether with the sets, costumes, or lighting, we cooled the image. I knew we were working a lot at night and in France the streetlights are sodium lamps, so the color is a light orange and yellow. But in the ’90s, the streetlights used mercury bulbs that gave off a blue illumination. So, the light was cooler. For each take on the streets of Rennes, then, we had to relight the street by removing the hot sodium streetlights and replacing them with cool mercury lights. It was actually a simple idea because we didn’t have the money to remake the ’90s so we re-created it with light. For me, the blue palette tells us about the ’90s better than trying to identically match every object from the decade. In this way, the color provides the idea that the story does not happen today; the story happens at a time that in fact still needs to be defined, and we tried to give it an idea. I’m happy with the outcome. I think the film’s artistic direction has a unity that is not necessarily always the case in my films. David A. Gerstner is Professor of Cinema Studies at CUNY, College of Staten Island and the Graduate Center. He co-wrote the book, Christophe Honoré: A Critical Introduction (Wayne State University Press, 2015).