Beware the movie based on literature, or, in that showbiz term of art, a “literary property.” Not because adaptations are an inferior form of cinema—I don’t believe that for a moment—but because they create an added layer of copyright issues for the film. When a movie stays long out of sight, and the studio still has prints, very often the reason you’re not seeing it has to do with the rights to its literary source. This is most likely why Lo Straniero, from 1967, directed by the great Luchino Visconti and starring Marcello Mastroianni and Anna Karina, has gone missing for so many years—never on VHS, never on DVD, unseen on TV, and infrequently revived in cinemas. It’s based on The Stranger by Albert Camus, and it has what J. Hoberman calls “complicated rights issues.” (In the 1990s it was reported that Camus’s daughter dislikes the film.) Consequently an extremely rare screening as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s 28-film Mastroianni series was mobbed. Whatever is keeping The Stranger out of American hands, it isn’t lack of quality. I wouldn’t rank it with Visconti’s greatest films, but the first half in particular gets under your skin, and stays there. Shot in Algeria, where the novel was set, it’s a sun-soaked movie, with exteriors in harsh yellow and glaring white that look as if they were filmed entirely at high noon. The buses, the cars, the cramped apartment buildings all seem to have temperatures and textures. Mastroianni sweats clear through his linen jacket; other characters mop their brows incessantly. The only one uncrumpled and perspiration-free in the heat is the perpetually cool Karina.

The adaptation is highly faithful to the book (reportedly at the insistence of Camus’s widow), even keeping the temporal setting of the 1930s. Mastroianni plays Meursault, a clerk whom we first see going to Marengo to bury his mother after her death in a nursing home. The home’s locked-in atmosphere and addled residents seem more akin to an asylum, but it doesn’t affect Meursault, who settles in next to her coffin, drinks coffee, and smokes cigarettes until the funeral the next day. Meursault, it seems, has very little in the way of ordinary human feeling, and zero desire to fake it. Visconti’s camera shift to close-ups again and again, of Meursault’s blank expression, of the lively and mobile faces around him. Algiers, where Meursault lives, is an intoxicating city, but he is immune. There is an extended shot of Meursault walking home at night, a hundred different noises swirling around him, detached from them all. Mastroianni, an actor of immense charisma, is an oddity as Meursault. Even his smiles of boredom or indifference reel you in; the charm is who he is, he can’t turn it off. It isn’t just his beauty, although that makes a late-movie line that he might have “wished for a better-shaped mouth” unintentionally amusing; a mouth more perfect than Mastroianni’s is hard to imagine. (Visconti is said to have wanted the even more handsome Alain Delon, whose stern reserve might have been less anomalous.) When Meursault chuckles at an old hobo who is screaming at a dog, or lights up next to his mother’s coffin, there is more there there than the character is probably supposed to have.

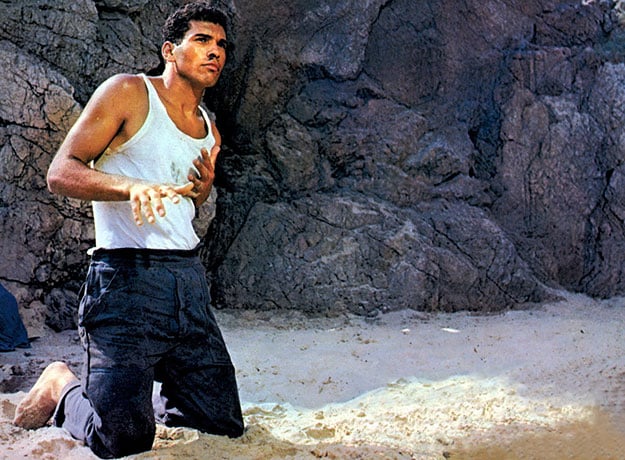

Overall, however, thank God for that. Existential anomie can be riveting on paper, but ennui is possibly the hardest and least rewarding thing that can be put on screen. And the actor’s Marcello-ness does make it easy to believe that dazzling Marie (Karina) would be in love with this phlegmatic clerk, who responds to her declarations by saying he probably doesn’t love her, but he’ll marry her if she wants. The climax of the movie comes at a beach house where Meursault and Marie are visiting friends of his Algiers neighbor, Raymond (Georges Géret), a brutish type who’s being pursued by the brothers of an Arab woman he roughed up. Visconti builds beautifully to the story’s abruptly violent climax, through the cackling of the women, the empty beach, and the sun drilling a hole in Meursault’s head. The Arab brothers have followed them there, and Meursault, walking alone and with a gun in his pocket, shoots one of the young men, following the first fatal shot with four more bullets. (The nameless Algerian has drawn a knife, a fact that would matter a great deal in the good old U.S. of A., but in the world of this movie is never once mentioned by anyone.) Meursault is taken to prison, and in a brilliant moment, is put into a large holding cell full to bursting with Algerians. What did you do, Meursault is asked. “I killed an Arab,” he responds. The absolute silence, and the pan around every face in the room, that follow this statement make for the most telling (and politically jarring) moment in the film.

The action of the movie then shifts to Meursault on trial for murder, where it seems that the prosecution is most interested in his bad manners at his mother’s funeral. It’s reminiscent of the nightmarish trial in The Lady from Shanghai—close-ups of homely lawyers, odd camera angles, nonsensical arguments, and an audience baying for blood. In the middle of it all is Meursault, unable to play at human feeling even when his life is on the line. Asked if he feels remorse, he will admit only to being “a little annoyed.” Sentenced to the guillotine, essentially for not crying over his mother, he retreats to a black-painted cell and an extended, highly philosophical conversation with a priest. Mastroianni, tasked in this scene with conveying the full freight of the movie’s message, does very fine work. But the best of the film lies in what Visconti and his star do with the beach, and the buildings, and the sultry atmosphere of The Stranger’s long-gone setting. The Stranger screens June 8 and 12 as part of “Visconti: A Retrospective” at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Farran Smith Nehme writes about classic film on her blog, Self-Styled Siren, and recently published her first novel, Missing Reels. She is a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.