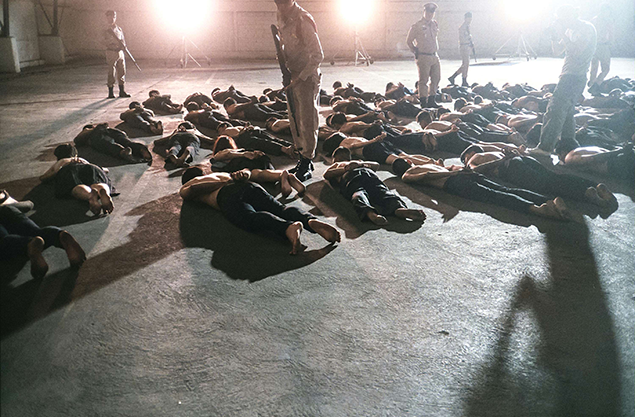

Her second feature, By the Time It Gets Dark, is a more overtly political film, taking place against the backdrop of the 1976 Thammasat University massacre. But instead of explicitly discussing the event, a thorny topic still subject to strict government censorship, the film examines the intangible forces of time, memory, and cinema, all of which blur the line between reality and fiction. Rarely mentioning the event, the film follows the everyday lives of characters that include a filmmaker, a pop star, and an unemployed woman constantly changing jobs, without explaining their connection to one another. As a humanistic portrait of ordinary people linked together by a turbulent history, By the Time It Gets Dark follows in the same path as the works of Thai directors Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Aditya Assarat, and Pen-ek Ratanaruang; but Suwichakornpong expands this idea to the fullest extent. Moving from country roads to expressways, and through photographs, films, and dreams, its many narratives converge into an Odyssean reflection on the effects of a single moment on the lives of many, even those who do not remember. Film Comment spoke with Suwichakornpong at the Locarno International Film Festival, where By the Time It Gets Dark (Dao Khanong) had its world premiere in the Concorso Internazionale. While many other films in this year’s competition centered the life of an individual, By the Time It Gets Dark has no central plot or main character, and its many pieces only fall into place when taken in as a whole, suggesting that no one person can be separated from the greater story at hand. The film opens exclusively at the Film Society of Lincoln Center on April 14.

What inspired you to write this story? There were many starting points. The Thammasat University massacre that is the impetus of the film happened in the year I was born, 1976. The first time I knew of the massacre, I was in my early teens, and I had a curiosity and desire to know more about it. So I can’t say that I know when I exactly started this project, because this idea has stayed with me since I was a child. It was always in the back of my mind. But to be very technical: I started writing the script in 2009, and in the beginning, it started with one narrative about a woman who keeps changing jobs. I wanted to talk about an ordinary Thai citizen and the contemporary society in which we live in Thailand. But over time, this idea of the massacre came back. The things I had written referring to 1976, such as the student debate about the rector of the university siding with the coup, were supposed to belong to another period. But in the past few years, Thailand has gone through very similar experiences to those we had in the ’70s—the same university even had the same situation, in which the rector was siding with the coup. It was a bit strange for me to write about something that was meant to take place in another time and is now becoming a reality again. Your previous film, Mundane History, is very patriarchal, in that it focuses on a man, his father, and his caretaker. By the Time It Gets Dark focuses more on women. In one scene, the filmmaker character has a dream where she sees her grandmother and mother, and there is a sort of matriarchal narrative running throughout. Can you explain why you chose to make the film with this approach? After I finished Mundane History, I intended to make a very different film, at least on the surface. As you said, that film was very much about patriarchy, so I wanted to go in the opposite direction. Not only for By the Time It Gets Dark to be more about women, but also geographically speaking, because Mundane History took place in one house, with this one I wanted to go all over the place. That is the reason why the woman who keeps changing jobs was moving around a lot, because I wanted to show different parts of Thailand and let the geography of each place come through and speak about the situations at hand. You mentioned at the film’s press conference that By the Time It Gets Dark is your love letter to cinema. At the same time, it’s very critical of cinema, especially the way in which film reduces history or politics. The relationship I have with cinema is very self-reflexive. Cinema, in some ways, has taken over everything in my life. And that happened very gradually without me realizing. Some people can be very professional, and keep their career and personal life apart. But for me, there is no line dividing the two anymore. Even if there is one, the line is very forced. So I find myself belonging, or succumbing, to the world of cinema, though I don’t know if it’s for better or for worse. Do you know what I mean?

I think I do. Even in the film, there are parts where you don’t know whether you are watching a movie, or a movie-within-a-movie, or if it’s just real life. But I have to say, quite a bit of it is fiction. People sometimes think it is very autobiographical, but as a filmmaker, or a writer, you do exaggerate the parts you think are more interesting. If I were to tell a story about my life, it would be very boring. [Laughs] This is not my life. There are many characters who are either not aware of, or whose lives are not directly related to, that collective memory of Thailand’s past. Why did you choose to depict history through people who may not know that they are being weighed down by it? I think it has to do with the fact that the political climate in Thailand is one of suppression. You can say that these people seem very indifferent to their past, or what’s going on socially in society. On the other hand, I wanted to contrast the present day, the general sense of helplessness, as well as the characters being unaware, with the burden of history. Maybe the characters don’t know but the viewers do know, and in a way, I wanted to grant more access to the viewer than the characters. The film deals with the recurring theme of birth, death, and rebirth. Technically, the movie itself also reborn as different formats, most memorably with a montage of glitches at the film’s end. Was the use of this technique a matter of personal preference or a deliberate choice? I’m sure it’s at the back of my mind, but it’s never really my deliberate attempt to have varied styles. There is the cycle of life and death and deconstruction, but it really goes back to this film being an ode to cinema. That is why there is, in the film, a mini-film. I wanted to cover the different periods of cinema, to the present day, where it is all digital, which is how the film ends.

Many people have compared you to Apichatpong Weerasethakul, but Thai cinema is very vast and diverse. Do you have any favorite Thai films or filmmakers? [Laughs] I think it is an honor to be compared to Apichatpong. I love his work. But I never deliberately try to extract, or even to articulate and be very technical about it. To be honest, when I watch his films, I’m very moved emotionally, and it’s not anything technical. I identify with it immediately, and I never dissect how it works. So I would say he is my favorite Thai filmmaker, but I don’t study his work intently. Some of the shots in the film behind the glass window reminded me of Syndromes and a Century. That’s funny, because that’s my least favorite film of his! [Laughs] I liked it a lot, I like all his work. But Tropical Malady is my favorite film by him. “By the Time It Gets Dark” is also the title of a Yo La Tengo song, originally by Sandy Denny. There is a wide variety of music throughout this film and your previous work, with even your short Graceland harkening back to Elvis Presley. What role does music play in your films? Even though I’m not a musician at all, I get inspired by music. I’m pretty helpless when it comes to music, but I think music is very evocative on a personal level. When I hear a note or song, I feel an emotion, and from that point onwards, I can start; I have an image in my head. Usually, that is how I begin my projects: with an image that comes from a song. What image showed up when you heard “By the Time It Gets Dark”? Actually I shot it, but it didn’t make it into the film. In one version, it was the last shot, but I decided against it—it happens. It was a shot of a motorway, with traffic coming and going.