Roja There have been movie musicals about psychotherapy and cannibalism, yet a musical about terrorism sounds like a South Park episode. But since the Nineties, Tamil director Mani Ratnam has included Kashmiri separatism, military gang rape, and suicide bombings in some of the most moving, powerful, and toe-tapping musicals in Indian cinema. These aren’t dour social realist films scored to a funeral dirge, nor are they laughable, over-the-top explosions of bad taste. Instead, using the tools of popular cinema, Ratnam takes all the conventions of the Indian masala—lavish musical numbers that erupt at the drop of a grenade, boy-meets-girl love stories, romantic montages set to power ballads, joyous weddings, kindly grandmas, stern but loving fathers, a bit of action—and forges them into vibrant motion-picture spectacles that raise more questions than they answer, and tend to leave audiences in a stunned hush. “Making a spectacle in India is easy,” Ratnam said in an interview with Kaiju Shakedown, but he’s doing himself a disservice. Because if what he does is so easy, someone else would have started doing it by now. This weekend, the Museum of the Moving Image is screening three of Ratnam’s most acclaimed movies: Roja (92), Bombay (95), and Dil Se (98), loosely known as his “Terrorism Trilogy.” Watching them in a post-9/11, post–Narendra Modi, post–Mumbai Attack, post–Gujarat Riots world frees them from the criticisms of the day that they were merely riding the coattails of popular events to achieve trendy notoriety. Now they feel more timely than ever. “I don’t know if I should be happy or sad that they still feel relevant today,” Ratnam said.

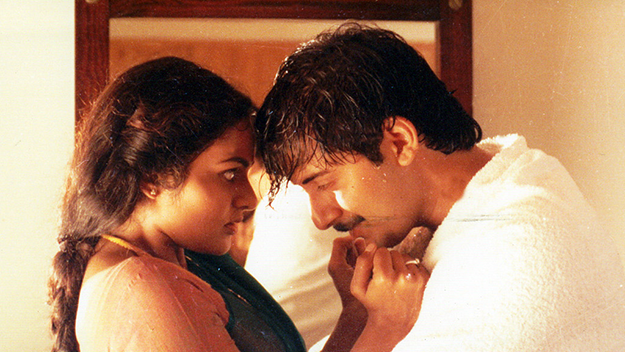

Roja The earliest of the bunch is also the roughest. Roja was an idea Ratnam carried around for years before deciding that he could deal with the issue of India and Pakistan’s dispute over the Kashmir region, a conflict that has sparked three wars, decades of terrorism, and left thousands dead, in a popular, rather than an art-house, film. Kashmir is about as far north and as mountainous a land as you can find in India—or, depending on which POV you subscribe to, Pakistan—so it’s a surprise that the movie begins in a small village in balmy Southern India where Rishikumar (Arvind Swamy) has just thrown over his arranged bride for her younger sister, Roja (Madhoo). Ratnam works in the small Tamil-language film industry based out of Chennai in Southern India instead of the better known Hindi-language Bollywood based out of Mumbai, so it makes sense that most of his movies are shot in the region. But there’s also a narrative method to his madness in Roja, which is revealed when Rishikumar, who works for RAW (India’s CIA), is assigned to a post in Kashmir. To most Indians, Kashmir is a place only dimly understood, mostly through news of the ongoing conflict there, and this is reflected when Rishikumar drops his South Indian bride into a new Northern life where she doesn’t speak the language or understand the customs. Ratnam underscores this by making sure that the audience doesn’t see snow in the movie until Roja herself sees it for the first time. Her situation gets worse when Rishikumar is abducted by Kashmiri separatists, and Roja tries desperately to pull every string she can to arrange his release. But in a region where she can’t even read a newspaper, her quest is more nobly quixotic than totally effective. Roja was shot by Santosh Sivan, probably one of India’s greatest cinematographers, and while Ratnam is very specific about the imagery in his movies, even in the script stage, Sivan shoots them with a muscular beauty, never more effective than in the almost-silent opening shoot-out amidst misty tree trunks that rise into a gray sky like the pillars in a cathedral, or with Rishikumar’s dash for freedom shot on Steadicam later in the film. Roja also marked the first collaboration (and the first film credit) for A.R. Rahman, a composer who has gone on to win two Oscars, two Grammys, and a Golden Globe, and who has worked with Ratnam on 12 movies. But impeccable technical credits aside, Roja is never more than what the posters bill it to be: “A Patriotic Love Story.” It broke box-office records, but it’s ultimately about a man who loves his country and a woman who loves her man, and scenes such as the one in which Rishikumar extinguishes a burning Indian flag by throwing his body on it feel unbearably corny today.

Bombay While the formula didn’t spark in Roja, it catches fire in Bombay. After directing a fun heist film (Thiruda Thiruda, 93) Ratnam turned his lens on the 1992 Bombay Riots which saw Hindu and Muslim residents of Bombay turn on each other in two months of violence that resulted in over 900 casualties. Most Indian filmmakers wouldn’t touch this issue, but Ratnam was protected in part by the fact that he was a Tamil filmmaker. “If you’re doing a Hindi film, you are exporting across India, so they tend to do lowest common denominator,” Ratnam said. “In a regional film we can afford to take a smaller issue and get it very rooted, dig deeper into that particular region, and that caste, and that community, and that practice.” The lower budgets of Tamil films also gave him more artistic freedom. Or, as Ratnam said: “It forces you. You have the freedom, but a little more budget would be better.”

Bombay Again kicking off in a tiny village in Tamil-Nadu, Bombay is a love story between a Hindu man, Shekhar (Arvind Swarmy), and a Muslim girl, Shaila Banu (Manisha Koirala). She’s clad head-to-toe in chador, but when he catches a glimpse of her face, he falls head over heels in love. The strength of Shekhar’s passion is off-putting as he practically stalks Shaila, disguising himself as a woman to get closer to her, and engaging in behavior that would earn him a restraining order in the U.S. “In India, the interaction between men and women is not as easy as in the West,” Ratnam said. “They grow up pretty much in different parts, and so for them to meet a person, and then spend time with them, and then fall in love is a thing that happens today. Twenty-five years back it was not so easy.” Shekhar’s father is an orthodox Hindu and Shaila’s father is a devout Muslim*, and the men can’t stand one another, nor can they stand the thought of their kids marrying. But after Shekhar moves to Bombay he sends for Shaila and she runs away to the big city where the two get hitched and have twins. The grandkids thaw the hearts of the fathers-in-law, and just when things seem to be headed towards a happy ending, the Bombay Riots erupt and transform the city into a burning Hell where roving gangs of Hindus and Muslims patrol the streets, setting fires and dragging people out of their cars to be lynched. Shekhar and Shaila’s mixed marriage is now a death sentence.

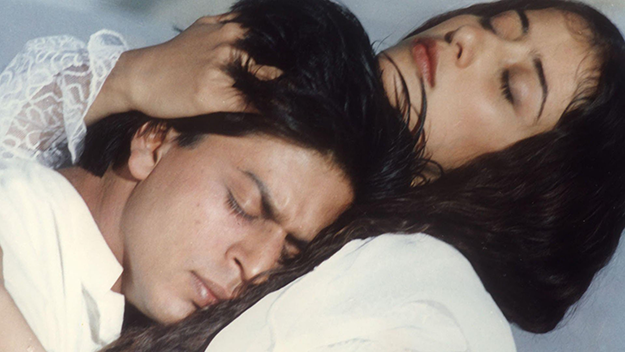

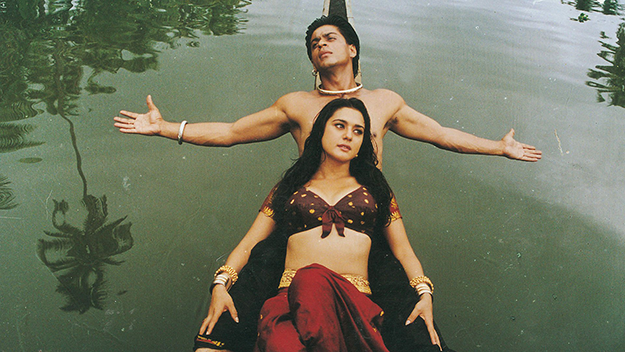

Bombay Shot with Chennai standing in for Bombay (“On our tiny Tamil film budget, the most practical way was to shoot it in Chennai,” Ratnam said) the riots build to a point of unbearable tension as the young couple’s apartment is burned, their neighbors are murdered, and their sons are sucked away into the surging crowd and get lost as their parents flee. Despite a last-minute happy ending, and the occasional “Why can’t we all get along?” speech, Bombay’s performances, editing, grand scale, searing setpieces (a particular harrowing moment occurs when the twins are doused in gasoline by a mob of Hindus who flick matches and demand to know if they’re Hindu or Muslim), and A.R. Rahman’s intense music transform it into a powerful river that sweeps you away. Dubbed into numerous regional dialects and distributed across India, Bombay was met with bans, protests from both liberal and conservative Muslim groups, outrage from Hindu nationalists, riots, bomb scares, death threats for Manisha Koirala, and a hospital stay for Ratnam after his house was firebombed. It also became a massive blockbuster, its soundtrack sold 15 million copies, and it picked up 17 awards both at home and abroad. Dil Se was something completely different. A box-office failure, it performed far better overseas than at home, becoming the first Indian film to hit the box office top 10 in the United Kingdom because it eschewed the populism of Roja and Bombay for a deeply felt poeticism that infuses every frame. Anchored by powerhouse performances from Shah Rukh Khan and Manisha Koirala, shot in shimmering shafts of light by Santosh Sivan, with musical numbers inventively choreographed by Farah Khan, and scored to now-classic songs by A.R. Rahman, it represents all six individuals working at the top of their game. The fact that it isn’t the subject of a slick, special-features-studded Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection says more about Criterion’s failure to embrace modern Asian cinema than it does about the quality of the film.

Dil Se It starts in an empty train station in the middle of the night. Amar (Shah Rukh Khan), a reporter for All India Radio, is waiting for the train when he encounters the mysterious Meghna (Manisha Koirala). He flirts, she stonewalls, and he finally goes to buy her a cup of tea only to return as the train pulls out of the station with her on board. All atmosphere, it plays like a short story or, as Ratnam said, “like a dream that’s come and gone, and you don’t think you’ll ever come across it again.” As this dream fades, it gives way to “Chaiyya Chaiyya,” a musical number staged atop a moving train that is arguably the most famous musical sequence in Indian cinema. (“Chaiyya Chaiyya” has not only appeared in Spike Lee’s Inside Man, but also in the Broadway musical Bombay Dreams, and been voted in a poll of 155 countries as the ninth-most-popular song in the world.) The rest of Dil Se is a fever dream spiked with surreal musical numbers as Amar pursues Meghna across the country with a single-minded passion that’s terrifying in its intensity, because it’s not just love he’s seeking. It’s death. In the story, set on the 50th anniversary of Indian Independence, Amar’s job as a radio journalist is to travel India recording the anniversary celebrations. “India was celebrating 50 years of independence, everything was glorious, we were talking about a lot of things which we have achieved, but there were corners which were darker,” Ratnam said. “We all believed at 50 years we’ve done tremendous work, and that is the front of the film, that is the color, that is the brightness, that is its sunlit look . . . At a time when we’re saying how excellent everything is in India, all of us know, all of us are aware that there are pockets which are burning.”

Dil Se It turns out that Meghna is a terrorist, a member of the United Liberation Front of Assam, radicalized by her involvement in the Kunan Poshpora gang rapes, a disputed incident in which members of the Indian Army are said to have gang-raped at least 53 women in the village of Kunan Poshpora during an interrogation mission. She’s now in Delhi, a bomb strapped to her stomach, ready to infiltrate a parade celebrating Republic Day and kill herself and the President. Its dark ending feels a long way from the optimistic climax of Bombay. The intensity of Dil Se comes from Ratnam’s desire for the movie to move through the seven stages of love as stated in Arabic literature: Attraction, Infatuation, Love, Reverence, Worship, Obsession, Death. This metaphysical framework gives the characters motivations that stem not just from the story, but from powerful, almost mythic forces. As Ratnam said: “It’s about getting drawn into a mystery. If I assume that everything is white, and then I see something which is not a white, I’m looking at it closer and getting drawn into it, seeing shades of it, like a magnet that pulls you in.” Dil Se’s deeply morbid ending stands in marked contrast to Bombay: the earlier film cranks emotions to maximum tension, and then, when all seems lost, Hindu and Muslim abruptly stop rioting and form a human chain to protect their neighborhood. As Rahman’s song “Malarodu Malar Ingu” pleads for peace and tolerance, the missing twins emerge from the crowd and are reunited with their parents. The human chain really happened (although it took place after the riots, not during their height), but this jarringly hopeful scene is more a product of its director’s desires than reality.

Dil Se “Bombay is the most metropolitan of Indian cities,” Ratnam said. “That’s where all kinds of Indians have co-existed for so long. If it was in trouble, then anywhere in India could have this kind of trouble.” He paused for a moment, and then went on. “I don’t know what I meant. I was hoping when I finished Bombay that it wouldn’t be relevant today. It should be a chapter from the past, but unfortunately it still seems to be relevant today, which makes you a bit sad, you know?” Watching the ending of Bombay when I first saw it in 2000, the ending felt optimistic and hopeful, a bit dreamy. Watching it today in light of the 2002 Gujarat Riots (790 Muslims dead, 254 Hindus), the Godhra Train Burning (59 Hindus dead, mostly religious pilgrims), and a host of other incidents of sectarian violence, it feels simplistic and naive.

Dil Se “But I think inside all of us survives a hope that tomorrow will be okay,” Ratnam said. “It will not be okay, but we believe it will be okay. Otherwise, I don’t think we can live.”

- In some casting sleight of hand, Shekhar’s Hindu father is played by Nassar, a Muslim actor, and Shaila’s Muslim father is played by Kitty, a Hindu actor. “We had them each play the other role,” Ratnam said. “This way it becomes a role, and subconsciously they know it’s a role they’re playing, and not a stance they’re taking.” LINKS! LINKS! LINKS!

Monster Hunt … Blockbuster alert! In China, Monster Hunt debuted less than two weeks ago and has already become the highest-grossing Chinese movie of all time with box-office earnings of $221 million. The fantasy film originally co-starred Taiwanese star, Kai Ko, but his scenes were reshot with actor Jing Boran after Ko was arrested in Mainland China with Jackie Chan’s son, Jaycee, while smoking pot. This disgrace has made the two young men poison for producers, but it hasn’t seemed to taint Monster Hunt, which made $52 million in its second weekend alone. … Speaking of Mainland Chinese scandals, Shaolin Monastery is now in trouble, as anonymous online allegations accuse Head Abbot Shi Yongxin (whose name means “Interpreting Justice”) of visiting prostitutes, raping nuns, embezzling money from the monastery, and fathering two illegitimate children since he assumed this high office in 1999. Some of these claims have been backed up with photographs, and some of it has been reported previously but swept under the carpet. Abbot Shi has been controversial since he took office, but this latest firestorm has erupted during the country’s current anti-corruption campaign and the noise is too loud for the police to completely ignore it anymore.

Terminator Genisys … So Korean star Lee Byung-Hyun appeared opposite Arnold in Terminator Genisys this summer, but you can’t blame the movie’s dismal performance on that. However, over at Korean Film.org they’re taking a look at how Lee’s performance plays into representations of Asians on screen and also why so many movies seem happy to show San Francisco falling into the sea or getting blasted to bits, but they don’t seem to be willing to show the Asian Americans who make up almost more than 30 percent of the population. … Speaking of “Where are the Asians?,” the Toronto International Film Festival has announced its main lineup. While many of the more Asian-friendly programs haven’t announced their schedules yet (Midnight Madness, Contemporary World Cinema Vanguard), it seems strange that out of the 49 films programmed, only five are from Asia. India accounts for three of them, which makes one of Mani Ratnam’s remarks in our interview particularly relevant: “Think of the impact Indians writing in English have had on the world over the last 20 years,” he said. “It’s time for Indian cinema to do the same.” Which it seems to be doing as Deepa Mehta (Beeba Boys), Meghna Gulzar (Guilty), and Leena Yadav (Parched) premiere their latest movies at TIFF. China’s Jia Zhang-ke fills another slot with Mountains May Depart, and Hong Kong legend Johnnie To has Office, his much-anticipated musical starring Chow Yun-fat, Tang Wei, and Sylvia Chang, which gets its international premiere after surprisingly not appearing at Cannes this year. … Eureka! Entertainment’s Masters of Cinema label is releasing a gorgeous 4K restoration of King Hu’s Dragon Inn on September 28, and there are plenty of reasons to be happy. This 1967 film is one of the most important wu xia movies ever made, and Hu’s movies have never been treated well on home video. Eureka!’s Dragon Inn joins the recent Carlotta Films 4K restoration of King Hu’s A Touch of Zen—but neither film is slated for a U.S. release. They’d seem to be absolute shoo-ins for the Criterion Collection, but as most people in the industry know, the surest way to make sure a movie does not get a release from Criterion is to make it Asian and in color. Trailer for the Dragon Inn restoration:

Trailer for the Touch of Zen restoration: