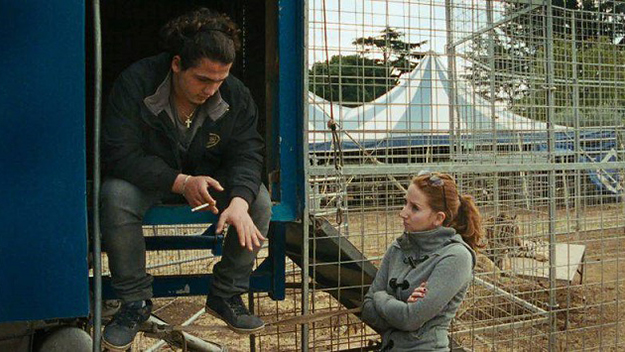

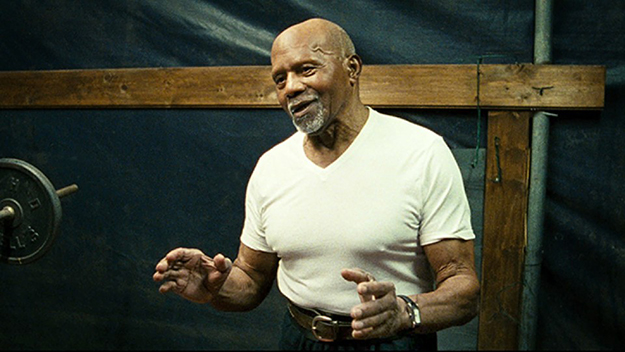

Mister Universo seems very much like a movie structured around characters who are presumably playing versions of their actual selves. I saw some familiar faces here—the mother from La Pivellina, for example—and from that film I know that you’ve been around circus people for some time. How did you assemble your cast here, and enter into their world? First of all, I have to say that you’ve explained our style of working perfectly. In this case, we had wanted to work with Arthur Robin for a very long time, because we’ve known him for 18 years now. And we were always thinking about doing a movie with him, but it wasn’t so easy for him. A lot of former Mister Universes become famous actors, but he has never worked in cinema. He’s had really good offers, but he had always worked in the circus. And in circuses they have engagements for a year, and you cannot miss a week. So with the decision to make a movie at 88 years old, you really have to trust the filmmakers. And because he’s known us for a very, very long time, he trusted us, and at the end he also very much liked the screenplay I wrote for him about a boy who loses a lucky charm and goes off to look for it. How did the connection with Arthur Robin come about? My partner—Rainer Frimmel, with whom I make my films—and I started in photography, not film, and our first work together was doing photographic surveys on little circuses in Italy and Austria. This was like 20 years ago, and at that time we knew so many fascinating people. We’ve gone to see the ones we really felt comfortable with every year, or every other year since—we didn’t lose them from our lives. So this is maybe how it’s come about that we’ve made a lot of films in the circus milieu, which is where we met Arthur. Because you are working with people who are playing versions of themselves, do you have them participate in the screenwriting process, or is it more a matter of spending time with people, getting a sense of how they talk, how they might act in certain situations? They never participate in the screenwriting process, but the dialogue is improvised. So in a way, they are a huge part of the screenplay because dialogue is what makes the film. It’s also important to say that we shoot chronologically, so that people, our actors, can really get into the story slowly. And eventually, they don’t know what’s real or not. So by the end of Mister Universo, Tairo really wanted to meet Arthur Robin, because he had spent so much time talking to people about him and looking for him. So this is something from which we are profiting, that people get so into the story. And we can document this. It’s for real. And they speak their own language, we just tell them what they have to talk about. So this keeps it documentary-like, which is very important.

So, Tairo and Arthur Robin had never met prior to their scene together? They never met prior! And I can see it in his eyes, when he first sees Arthur Robin, how happy he is. So to capture this, to make something that is fiction also real, is something we like very much. I’m assuming the extended family that Tairo visits along the way are in fact his actual extended family? Yes. How long was the shoot and what was the itinerary for locations? I don’t know where we are throughout the film other than we’re going north through Italy. We started chronologically, really, at the circus, in the south of Rome, and then we went to see his parents. But the problem is that they move all the time. So we couldn’t just write in the screenplay, “They will be in Pesaro,” because when we began shooting they surely wouldn’t have been there anymore. So it all depended on where people were; we couldn’t have prepared a place, but we knew the families very well. Throughout the movie, you have Tairo going to various people’s houses and basically being waited on as a guest, displaying this real sense of entitlement as his hosts make a big to-do, waiting on him. And then when he finally arrives at Arthur Robin’s trailer, it’s the first time you see him doing anything constructive for anybody else, getting the water back on in their trailer. That they didn’t have water was something that was not written. But the water didn’t work, and they went 10 days without it. So Tairo offered to take a look for them. This was something that just happened. For the story, it’s beautiful; Tairo comes because he wants something—he doesn’t get it, but he leaves something for them instead. When you work with such an open screenplay, these are the luckiest things that can happen. Something that seems to run through the movie is this motif of moving against the grain. For starters, there’s the scene involving a bottle that rolls uphill… Can you talk a little bit about that? There’s this downhill street in the south of Rome that we discovered about 15 years ago where everything rolls upwards. Rainer and I have been there several times in the summers, trying it out. It’s so fun because you go down there with your car, stop the car, and then instead of running downhill, it goes slowly upwards. It’s such a strange feeling. In the film, we talk a lot about counter-movements: when Tairo walks in the opposite direction of the religious procession, or when the candle against the evil eye is put out to drift in the water and instead gets pushed back to the shore—which is a scene that wasn’t written, it just happened. The scene with the street, though, was written. We wanted to have it, to show these people who are in a way also going against the stream. This traveling circus.

Once you’ve picked out who you want as your performers, what is the process of preparing someone like Tairo, who is not a trained-for-the-camera actor, to make a film? We always say that every person in the world is able to play himself. So we never try out how a person really acts for the camera. When we shot with Arthur Robin, we didn’t know how it would be. You have to be a good director, because it’s important for people to know that they don’t have to be any better, or any more beautiful, than they are in real life. Or any more gentle. That they really just have to be authentic. Our hardest work is this, to make people feel comfortable, and to understand that they don’t have to be someone else. Something that seems like it might be an issue is working with people who are, in fact, performers, but performing in a very different register. Have you found in working with the circus performers that there’s an element of the stagecraft inherent to them? Maybe they are great with the camera because they are used to being looked at. But I also think Italians are really good actors. With Tairo, this wasn’t the important thing, but Tairo had already worked with us, so he knew us. For young boys, it’s always a matter of being cooler, or that their story should be more dramatic. This is something we couldn’t provide him with, but I think he is very heartwarming nevertheless. There’s another performer that I really have to ask you about, and we get a little biography on him in the film: the aging chimpanzee, who has apparently acted for Fellini and Argento. That’s true, yes, and for us, that’s a story that conveys another life. Well, maybe not another life, but another area. In the end credits, we dedicate the film to all the people who have lost their jobs because of digitalization. Because we still work in film, and with film laboratories, which are empty now. And Lola the chimpanzee is also a little part of this world, which is going to vanish from us. We wanted to shoot this scene with the chimpanzee because of this story, and Tairo’s stepfather is the animal’s trainer, so we didn’t have to look too far. I think a lot of the movie’s charm comes from the fact that it allows us to see people and animals interacting in a way that you would never get in contemporary pop cinema. For example, a movie like Howard Hawks’s Hatari!, which relies so much on the pleasure of seeing Elsa Martinelli horsing around with an ostrich or a baby elephant, would not exist today—it would be a CGI leopard and so forth. It’s a post-Jumanji world. This was important for us. I don’t want to judge these relations. I don’t want to say if it’s good or bad to work with lions or chimpanzees. We just want to show how it can be, and to show that maybe it’s not like someone would imagine. It’s surely something that will vanish completely, as you said. It will vanish completely in cinema, because you can do it digitally, and it will completely vanish in circuses. They already have more and more problems traveling with animals, because they need a really huge place for them, and it costs a lot of money. I am sure that this will vanish, but for me the most shocking thing was when I was sitting in the circus, and while Tairo was doing his number with the lions, there were two kids in the front row, sitting and playing on their iPads, which was more enticing to them. They didn’t watch the lions once—they didn’t care. So I think it’s an art that’s going to vanish.

Having been around circuses for at least 20 years, you’ve probably seen some drastic changes. I can say that it’s like in every business nowadays: the small ones won’t survive. It’s always the big ones—like in economics, like in art, like in cinema—that get bigger and bigger and that will gain more money and more interest. This is the direction the world is going. And as someone who maintains a small and artisanal practice, you must feel some of the threat yourself? Exactly, because my cinema, our cinema, wouldn’t survive without festivals like Toronto, because our cinema needs them. So if at some point there aren’t as many festivals, or they have to show just huge things, this kind of cinema will also vanish because we will not be able to do it any longer. So I’m really grateful for and also dependent on festivals. Through them you find a public. Not to be able to share your work is a very sad destiny. Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.