The Trouble with Being Born (Sandra Wollner, 2020) Among the prizewinners in the inaugural Encounters section at the Berlinale were the latest film from Cristi Puiu, Malmkrog; an eight-hour seasonal portrait of a Japanese farmer, Works and Days; and Sandra Wollner’s The Trouble with Being Born, which ably holds its own. In Wollner’s second feature, a lifelike android (“Ellie”) lives with a middle-aged man in an isolated house, and as the deeply disturbing nature of their relationship emerges, the film pivots unpredictably into the world of a lonely elderly woman. Wollner’s hypnotically shot film escapes the usual beats of robot parables through an unnervingly muzzy sense of point-of-view and memory, and a delicate control of tone, with the creeping sense of technology as perpetuating trauma. Several days before her film’s Special Jury award win, I sat down with the Austrian-born Wollner, who had a wry eye for the dark absurdities of android technology and its implications. The Trouble with Being Born has its U.S. premiere in New Directors / New Films. Technology seems to reflect the worst in people at times: the child android in your film simply becomes a vessel for trauma. I don’t think technology makes the problem worse, because I think it’s something that was always there. I didn’t want to make a dystopia about how technology is going to bring out the worst in us, or how it is going to rescue us—this idea of technology being the evil or the good part—but more about how it’s always a mirror for our inner, darkest, weirdest thoughts. How did you arrive at the idea for the film? Roderick Warich, the co-author [of the screenplay], had the original idea to make this film about a childlike android. What I found so fascinating was the idea of showing this object that does not care about all of our troubles. It’s there to fulfill a desire but, of course, it never can, and it is not heartbroken when it is not used by this 50-year-old man or when it is used by this old lady. In a way, it is a continuation of my last film, also perspective-wise. I had the feeling, “Okay, I’m not done here.” My last film [The Impossible Picture, 2016] was about the building up of a self, like an ego, and this film was more like the disappearance of an ego, the dissolution. What research did you do on the current possibilities of AI? Of course you have the sex dolls that are out there that look horribly realistic. They are not AI, they are just dolls. AI-wise, it’s like a toaster. They can talk. There is this guy who sells these dolls, age four to age 14, and he says that people buy them because they want to play with them and they are isolated and alone. I found that quite disturbing and interesting at the same time. It shocked me, but with our virtualization of our whole world, I think our inner pictures and outer reality are coming closer together. That is what I found fascinating, and that’s why I had to pick this drastic picture, because I was so disturbed.

It’s beyond disturbing. It all recalls what the internet does well: there can be a complete withdrawal from norms and morality and society at large. Here, you have a scene where the middle-aged man who has the doll goes out to a bar, and he kind of shuts down. He is all by himself. The whole idea of virtualization brings us back to our own isolation. I don’t think that’s something that was not there before—it’s something that’s deep within the structure of a human being that we always have to ask ourselves: how do we really get out into this world, and how aren’t we ghosts in the shell? How aren’t we just that, within there, and always have to fight to get out there? I don’t necessarily think that the virtualization brings that out in us, but it shows us the ghosts that we always have been. You mentioned the loss of ego. The film seems to start with the birth of a point of a view, showing us abstract, opaque imagery. How did you design those visuals? Our VFX supervisor built an algorithm that basically works like Google DeepDream and we fed it with all the pictures we had and tried to put it on other levels of the film. I didn’t want it to look too digital. I wanted it to have this anachronistic feeling—also cinema itself, maybe. Is it a film? What does it look like? My last film was set in the ’50s, like a home video. It was like the journey of an ego becoming itself through the perspective of a camera, and for me, this film starts where the perspective of the last one left off. Where inner pictures and outer realities came together. This was the idea for the very beginning: Ellie talking about herself from an ego perspective, but it’s an android voice recognizing herself just as an object. That’s what I thought interesting. Even the way you set up the shot sequence to introduce her in the beginning, it keeps us off-balance. The narration and also the perspective—we can never be sure that this is what it means. That is something I love in cinema: to be not sure where I am, in a weird dream or… Are there any films that come to mind like that? I can go with the clichés. There is Lynch but also Claire Denis. There are so many filmmakers I was influenced by, just dream-wise: Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Jonathan Glazer—for this film, specifically. Something more like a metaphysical cinema. I just love it to be somewhere in a weird dream where you cannot solve a riddle, and I think that is one power of cinema: to go there and be drawn into something and get lost and confused. That’s something I only feel in cinema. Maybe theater. But I cannot find that in a series or something else.

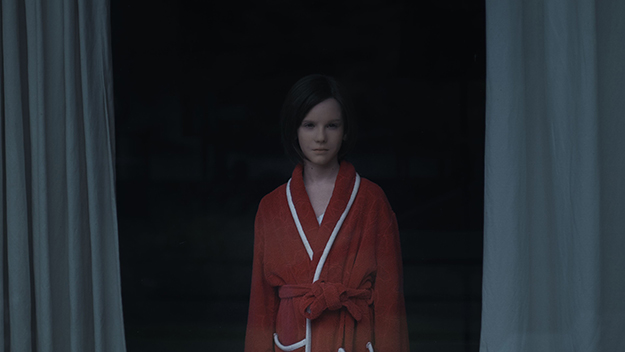

The color palette and the lighting also have a dreamlike, indistinct quality. My DP [Timm Kröger] is a director himself, he’s very involved in my projects. What I love about him is that he works with really so little. Specifically, with the colors, we were always thinking about something like her bathing suit and his bathrobe, and everything had for me these weird ’70s colors. His house is built in the ’60s. You cannot put a finger on exactly what time it is. Of course, smartphones are in there, but I wanted it to be a little off. And this feeling of half-light. The middle-aged man practices tennis at dusk. Because that’s what you do. I couldn’t get rid of that picture. He’s playing by himself. He has this super technical android there, and then he has this old, rusty [tennis ball] machine going “15-30!” You were talking before about memory. The android’s voiceover sounds like she’s trying out memories, or practicing them. But that’s not the convention in movies: if you hear a voiceover, you can think it’s their actual self. In this case, the self does not necessarily exist—it’s just words. That was jarring as well. That was the idea, to have someone who’s trying out sentences, like someone who’s trying out a shoe. Does the sentence fit? That’s what I liked. This is voiceover coming from somewhere out of eternal time frame, where you don’t know whether it already happened or will happen. Like a loop, but more like a [figure] eight—this loop going there and there and there. There’s also the question of whether the android has free will. I tried to grab something like the antithesis of Pinocchio. Not the idea of oh, he wants to become a real boy, or, whatever, conquer the world. But more that he does not want anything—he just wants what you tell him to want. Pinocchio just tells us the story of what we want to have. In some way it’s comforting to think that a robot wants free will because it’s what we value. Maybe they don’t care at all, which is scarier. Maybe it is an American thing as well—free will for robots. Yes, AI, for example: when Kubrick wrote it, it already was the Pinocchio story. Then again, I was thinking a lot about AI. That our film would be the opposite, a more European, darker version. But then I thought, was it true in the first place in AI, did he really want to become a boy or was it all along in the programming? At first I thought there was this wish in this boy which they programmed him to have. That’s even more cruel than what we are doing in this film! They programmed this boy to want to become human and then they put him out there. Do you think of your movie in terms of science fiction, or would you rather just think of it as a drama that happens to be in the future? I always tried not to make it in a science fiction setting. First of all, I did not want to do that, but also we would never have the money to do that. Science fiction is quite expensive, so you better make it a fairy tale. I love Under the Skin. It was a reference for us, even though it’s a completely different thing, an alien coming to this world. How did he show it and how did he bring it into this real world? I was so struck when Scarlett Johansson walked through the mall and how they just shot it. How did you work with the actor playing the android? She’s so young—she had one short film before. It was great luck to meet her and her family. It’s so important, with such a film, to talk about such things in a child’s way. She’s wearing a silicone mask all the time, so she does not look like that at all. “Lena Watson” is a [stage] name that she chose so she can choose, later on, if she wants to be related to the film. She was there every day, and it was quite an effort to put the mask on her face, for one and a half hours, so she really slipped into that role and was someone completely different. And of course she was not running around naked—this was all VFX shots. She was always dressed and no one saw anyone naked and she did not see a naked man. We maybe just traumatized our audience but not our actors.

The times when she has a vacant look, it’s terrifying. She’s wearing the silicone mask all the time. Yesterday she was at the premiere, and when she came out and was like, “Oh, it’s so lovely to work on this film!” everyone was so shocked. I thought it was some form of mild VFX adjustment. The fuzziness goes with this feeling of an indistinct person. It was quite important for two reasons. One is to have this sense of uncanniness. And it’s also to look like this girl that she should look like. It’s also fascinating when the android is reprogrammed later for the older woman. Fundamentally, the android does not have gender, because it can be whatever its role is supposed to be. For this object, it is arbitrary because it does not care about anything. Also, such categories as gender or morals or age or race or whatever are not even categories for it. That’s what I found interesting. Those scenes with the older woman remind me of documentaries I’ve seen about elderly home residents who get little stuffed animals that make noise, and they love it. They have someone to take care of so they feel needed again. I’ve seen so many where they have these little, lifelike babies—they feel like a human being again. They use it for dementia treatment. But I also found it interesting to have this situation of an elderly lady that gets an android from her son: here is your android, Mom, we’ll switch its face, no problem! I find it very funny and weird. Given the striking story, has there been interest in any sort of remake? I just talked to our sales and some people were interested in the film but without the naked scenes. I am not insisting on the nudity but I am insisting on the thing being an object. I don’t know… who would want to remake it? We always thought it would be a great manga.