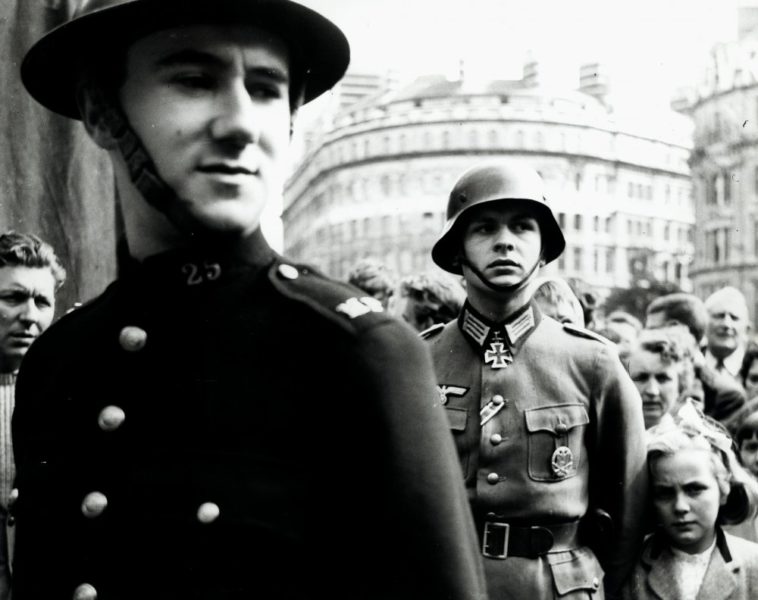

With co-creator Andrew Mollo, Brownlow pioneered an experimental, documentary feature style in both the original “what-if movie,” It Happened Here (1964), which depicted a Nazi occupation of England, and the historical film Winstanley (1975), which re-created Gerrard Winstanley’s 1649 attempt to establish an agricultural commune on radical Christian principles. (Mollo, technical adviser on Dr. Zhivago, would go on to work as a military consultant on films like The Pianist and production designer on the popular Richard Sharpe and Horatio Hornblower TV movies.) Peter Watkins cut his teeth as a bit player and production aide on It Happened Here, then applied its lessons to his own films, such as The War Game. Peter Suschitzky shot It Happened Here at the beginning of a brilliant career containing a 26-year-and-counting run as David Cronenberg’s cinematographer and other credits like Watkins’s debut feature, Privilege (1967), and The Empire Strikes Back. (Mollo’s late brother, John, was the costume designer on Empire and the original Star Wars.) Tony Richardson provided crucial financial and moral support for It Happened Here, then hired Brownlow to edit The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), one of the most gorgeous and audacious of all British historical epics. To help inspire Richardson, Brownlow showed him the cavalry charge directed by French master Raymond Bernard in the 1927 silent movie The Chess Player, which Brownlow and David Gill (who co-founded Photoplay Productions with Patrick Stanbury) later restored for Thames Silents at Thames Television (the home of their Hollywood series). Brownlow brings a revivifying, you-are-there quality to all his work. He forges links not just between films but also between movie history and social and cultural history. His vast appetite and simmering ebullience have fueled cinematic scavenger hunts that yield real treasure thanks in large part to his energy and care. I spoke with him on Memorial Day. The next morning he flew out to San Francisco for a celebration of his 80th birthday, on June 2, at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival.

Mare Nostrum How does it feel to be getting a birthday salute at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival? It’s very kind of them. I just wish it was a much earlier one, but there’s nothing they can do about that! Why did you choose Rex Ingram’s Mare Nostrum [1926] to show for this celebration? Rex Ingram has been quite forgotten. I very seldom come upon a screening of anything he’s done. The last time Photoplay restored one of his films it was The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse [in 1992]. I was quite used to seeing it in the versions available over here, but it looks so much better and is such a better a film when you see it as it was released in 1921. When it was reissued the year Rudolph Valentino died, in 1926, it coincided with a number of treaties in which European countries agreed to try not to go to war with one another. So they cut out scenes of a German orgy and executions and so on. Editing out those and a few other scenes made it a much less interesting picture. It was marvelous to restore them and add a really stunning score by Carl Davis. And it’s really frustrating that Warner Bros. has yet to fulfill its promise of putting that out on DVD. They did do Ben-Hur [as part of the 1959 version’s collector’s edition] and Flesh and the Devil and The Big Parade. But they were going to put out all the MGM restorations we did at Thames Television. They included The Crowd, The Wind, and Show People, most with marvelous scores by Carl Davis. When I located the original negative of The Big Parade, they did a marvelous job with that, and they must have been disappointed when it failed to meet their financial expectations. Still, it’s a form of commercial censorship. Is Mare Nostrum, to your mind, one of Ingram’s best? I think so. It’s again a wartime subject and it was banned in Germany. It’s got a marvelous performance by Andrews Engelmann as a U-boat commander. He was so effective as a villain that after seeing the movie Fritz Lang told him, “You are no longer German!” Which was quite true because he wasn’t German [but was instead born in St. Petersburg and later became a Swiss citizen]. David Lean absolutely adored Rex Ingram. He said that when he saw Mare Nostrum, and the movie cut to a low angle of Engelmann at the periscope—that’s when Lean knew that there was someone directing the film. Rex Ingram and Erich von Stroheim were close friends. And they both shared a fascination with authenticity, which makes a lot of difference to a picture. Didn’t you and Andrew Mollo turn “authenticity” into your aesthetic when you made It Happened Here and Winstanley? Yes, Andrew converted me. Talking about authenticity—something extraordinary happened pertaining to It Happened Here. An Italian documentary on Nazi propaganda was presented a few years ago, by [the Italian government broadcasting agency] RaiTre called La Grande Storia. I heard from a friend in Italy that they had found a film made by the Germans to prove to the occupied territories that they had invaded England. They got it from a man named Fritz Hippler, who actually lived in Berchtesgaden. One of the researchers on this production went to see him and brought all this footage and put it in this documentary. And nobody turned a hair except Andrew and me. When we finally saw the tape we realized we had shot everything in that “German propaganda film.” [Laughs] The Conquest of England: 1941. I would have been three when it was made and Andrew one. Fritz Hippler had directed The Eternal Jew, which was the most appalling anti-Jewish film—showing the Jews as rats—and he became the Reichsfilmintendant, the organizing head of the film industry under Goebbels, and then went to live the rest of his life in Berchtesgaden, of all places. I remember ringing him up, because I wanted an interview with him for another film. You know, when Germans answer the phone, instead of saying hello, they use their surname. And this fellow picked up the phone, when I was ringing him in Berchtesgaden, and said “Hippler!” [Laughs] It gave me quite a turn. By the way, when I objected to RaiTre, the fellow who did the deal said, “Well, we have a rule in Italy—with film, we do anything we like.” I asked whether that rule was passed by Mussolini. And he said, “Yeeesss!” Well, having your film used that way was a wonderful outré compliment! That’s what Andrew felt. [Laughs] It’s hard to imagine you holding these two obsessions in your head—doing groundbreaking work as a film historian while also co-directing incredibly ambitious, low-budget features. How did you do it? Well, it took forever to do It Happened Here. When I started I was earning £4.10 a week [at World Wide Pictures, a documentary film company, based in Soho, London], and when I met Andrew he wasn’t earning anything at all, he was an art student. I persuaded him to take part in the production and then showed him some of the footage I’d done. He was appalled. He had expected it to look at least as professional as what you see in the cinema. And my footage, to him, and later on, to me, was incredibly amateur. He said, “Everything in that was incorrect!” Could you imagine that? [Laughs] He said he wouldn’t want to work on it if I kept that footage, we would have to start all over again. There was such a difference between what we shot when he was on the picture, supplying all the uniforms (many of which he bought from a Düsseldorf air-raid shelter), props, and even some of the military vehicles, that I did really scrap all the early stuff and start again. He wasn’t a film specialist but often spoke of Erich von Stroheim. I’d say, “I thought I was the film historian around here.”

It Happened Here To me, there is a straight line between what you love about silent films and what you try to do with your own sound films. Finding what’s expressive on location, in props and costumes, in the physical presence of the actors, who were mostly non-actors. Yes, that’s very true. The problem is, I realized that had I the talent, it was possible to do something like The Grapes of Wrath [laughs]—but there’s such a difference between It Happened Here and Winstanley and what John Ford did with The Grapes of Wrath. Carl Theodor Dreyer exerted a big influence on Winstanley, as did Arthur von Gerlach, who directed The Chronicles of the Grey House, a picture set during the Thirty Years’ War, and was one of his only two features. David Caute, who’s had a long career as a novelist, historian, and journalist, wrote the novel Winstanley was based on, Comrade Jacob, as well as the “working screenplay.” One of the behind-the-scenes dramas in your book [Winstanley: Warts and All] is about you and Andrew going on location and using Caute’s script as a jumping-off point. That’s like silent filmmakers going out on location and using the script as an outline, or throwing it away to rely on original or firsthand sources. We went to the British Museum and consulted the original pamphlets that Winstanley had written in 1649, and there was so much there that was impressive—his writing was brilliant, absolutely brilliant. I can understand why David Caute was upset with us, but that stuff was irresistible. It was so strong. When we were at the British Museum it was hinted that these documents had been examined by Marx, by Engels, and by Lenin. And there’s a statue of Winstanley in Gorky Park. The only thing is, when we showed it at the Moscow Film Festival, about 40 people got up and walked out, all together, as though they were ordered. It was most uncanny! I asked the man who managed the place, “Why did they all walk out like that?” He said, “You make political films, like we do. We want American films!” Talking about silent films and sound films—and Russia!—Alexander Nevsky is a sound film, but of course Eisenstein developed his techniques in the silent era, and you use Prokofiev’s score to Alexander Nevsky in the battle scene. We tried everything we possibly could! We were really convinced we should not put Russian music in a film about England. And we went through hell trying to find something—effects—anything. But we came back to it because this was perfect. The battle scene reminds me of the one in Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight. In her famous review of that film, Pauline Kael theorized that it was so brilliant partly because Welles didn’t have to worry at all about syncing the dialogue in the soundtrack. It reminds us of the freedom silent filmmakers had. Yes. And incidentally, the armor and all the weapons in that scene were loaned by the Tower of London Armouries and last used in the English Civil War. Another great director, Tony Richardson, was crucial to you being able to make It Happened Here, and he later hired you to edit one of his best films, The Charge of the Light Brigade. Editing that film was a wonderful experience, but alas it was not a success. Because of your association with Richardson, and with Lindsay Anderson, who went on to narrate documentaries for you, did you have a sense that you were part of a movement of filmmakers? I did rather hope, right at the beginning, that I would only have to do a sample sequence, and producers would fall over themselves to back it. And that did not happen until Tony Richardson. Andrew was working for Woodfall [Richardson’s partnership with Harry Saltzman and John Osborne], and at the time they were producing Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Andrew didn’t think you could do that sort of thing—ask for money from someone you were working for. Luckily, Tony came up to him and asked him how the film was going and then, after watching some of it, asked if we could do the film for £3,000. We only went 100 percent or so over budget. We made it for only £7,000. What was it like working with him on The Charge of the Light Brigade? It was very curious because he was very self-deprecating. I feel so affectionate toward him. He’d say, “I made a mess of it.” He was talking about the landing at Calamita Bay. He said, “I don’t know what you can do, but try and save it.” And it was superb, absolutely marvelous. And it looked terrific when it was cut together, and he was amazed. That kept on happening. It was really enjoyable. It hardly had to do with the editing. The action was marvelous, as were all departments on that film. Remember the amazing animation of Dick Williams? He was working on the animation practically to the day of the premiere. The Victorian crosshatching—it must have taken ages to do just one frame of that. By now, you’re primarily associated with silent films—restoring them, as in the lifelong undertaking of restoring Abel Gance’s Napoleon, and chronicling them both in books and documentaries. Are you hopeful that the silent-movie audience is growing, especially at festivals like Pordenone and San Francisco? It’s very touching to discover young people who feel so strongly about silent films. When Pordenone started, with Livio [Jacob] and Piera [Patat], I didn’t go there at the beginning, damn it, and I missed a lot of very important things. When I finally realized I ought to go to Pordenone, the enthusiasm for the films was really terrific. The same thing in San Francisco. The enthusiasm of the audience is simply wonderful. I once made a film about Abel Gance, and he ended the whole thing by saying, “While I’m on television I want to tell you that enthusiasm is essential in the cinema. It must be communicated to people like a flame. The cinema is a flame in the shadows. Fed by enthusiasm it can dispel them. That is why enthusiasm is everything to me. It is impossible to make a great film without it.” Let’s talk about the difference between directing your feature films and directing your array of documentaries. It seems you and your collaborators on these nonfiction films, first David Gill, then Patrick Stanbury and Christopher Bird, insist on giving them a certain liveliness and visual vitality. Right. How did it start? It’s usually someone who steps forward and helps you get it done. There’s a fellow called Barrie Gavin, who was a very prolific director at the BBC, and he was asked to do a series on the movies. And said to me, “Why don’t you make a film about Abel Gance?” He hadn’t seen Napoleon, but he’d heard me going on about it. We only had half an hour and £1,000, but he managed to get it brought up to one hour and £2,000. So it was possible to afford the footage and the trips to Paris to interview Gance and [lead actor Albert] Dieudonné, and that was the first lot of interviews I filmed. Then I thought, “Why are we just doing this to one great French director when there are so many American directors overlooked by film history?” I tried to get [British broadcasting company] Associated-Rediffusion to play with the idea of doing a history of silent Hollywood, but they dropped it. It wasn’t until I finished Winstanley that things started to happen. I was so stunned by The World at War, which Jeremy Isaacs produced, that I sent him a fan letter. And he wrote back, “The extraordinary thing here is that I’m currently giving copies of your Parade’s Gone By to the people who worked on The World at War.” He thought there was another series in it. I thought doing a television series would cure me from ever wanting to work with silent films again. How could I expect TV people to have the slightest interest in silents? What was astonishing was that the partner I was given, David Gill, was even more rigorous than I was. During World War II, at his boarding school, he had worked on the music for the silent films that they showed at the weekends. Again, the enthusiasm behind the series was terrific. We had to go to Hollywood to test one or two old-timers to see what they could deliver in an interview. The first was Lefty Hough, who was John Ford’s property man. He had us absolutely in hysterics. The secondary producer, who had come out with me to check on these people, said, “six more of those and you’ve got a series.” We interviewed between 60 and 80. Very lucky. Hollywood—such an unimaginative title for the series, but we just couldn’t come up with another one that fit everything we had.

Napoleon What’s the difference between doing an overview series like Hollywood or Cinema Europe and dealing with individual subjects, like Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and D.W. Griffith? They’re completely different forms. The Unknown Chaplin began purely by accident. When we began to examine the rushes from his Mutual days, we had no idea whatever how Chaplin really worked. Chaplin didn’t want to tell anybody because the worst thing you could say about people in the film industry is, “He doesn’t know what he’s doing.” But that was the clue! Here’s the most successful filmmaker ever and he didn’t know what he was doing. He would go on and on and on until something clicked in his mind and he thought, “This is it.” Fifty takes, 30 takes. Sometimes you simply couldn’t tell the difference. It was quite amazing to see the discipline behind the uncertainty and how everybody went along with it. Sometimes he would turn the story completely upside down halfway through. He would see how another man would play a role like the drunk in The Cure—while he was playing a bellhop—then take it on and make the drunk the lead role. He’d start a film like The Immigrant as sort of a La Bohème French-café comedy and end up with this wonderful picture about an immigrant who had no money going to eat in a restaurant and watching another customer getting beaten for not paying up. Finding that footage was an extraordinary occurrence. We all went in with preconceptions but they changed as we worked on it. Trouble was, we found 300,000 feet of Chaplin rushes from the Mutual period [1916-17], and then we thought we’d get the same sort of amount on Keaton, and we got 50 feet! So how did you refocus what became Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow? We had a meeting and decided, “Oh, come on, it’s really worth doing his career.” It was so amazing. What was a surprise was going out to Cottage Grove, near Eugene, Oregon, where they shot The General, and to discover from the people who were in the National Guard, and played in the battle scene, how dangerous it was for them—they were nearly drowning. The civilians who watched the train crash were convinced it had a real engineer because they saw a dummy and were persuaded it was the real thing—it was so dramatic for them. The original locomotive that crashes through the bridge into the river sat there from 1926 until it was moved out during World War II. For Harold Lloyd: The Third Genius, did the thrill come from introducing new audiences to the work of a man who people didn’t realize was the equal of Chaplin or Keaton? Yes, that was it. And showing how terrifying it was to go up a 14-floor building onto a flat roof where he had hung off the clock and had to keep sinking his feet into the bricks of the façade where the clock was hanging from. How did they get the idea of how to do that? Because it was an optical illusion, and in our film we pulled back to show how. Lloyd was so courageous, he did so many of his stunts with half a hand [having lost the thumb and index finger of his right hand handling a prop bomb that turned out to be real]. You also did a D.W. Griffith documentary, and now Twilight Time has released a Blu-ray of the Photoplay restoration of The Birth of a Nation, which contains a piece by Patrick Stanbury on the restoration and your plea that we never censor the past. You ran into censorship yourself with It Happened Here, when you recorded the words of contemporary National Socialists in Britain. Distributors and some Jewish groups thought the film could be promoting anti-Semitism. Andrew and I felt very strongly that it’s a great mistake to suppress people. The forbidden becomes exciting and very attractive to nutcases. The Nazis certainly revealed themselves to be mental cases and quite terrifying. We couldn’t put the worst of it in. What we did was to try and tell people what National Socialism was. To my knowledge, there isn’t a single feature film made since the War, since the Nazis stopped making propaganda films themselves, that actually tells you what they planned, how they intended to treat people, all those sort of things. That has been taken over by actors frothing at the mouth and screaming against Jews. You see that and you’re supposed to think, “That’s a Nazi for you.” Pure melodrama. Around the same time you were working on the D.W. Griffith film, you were writing your biography of David Lean. Like Alfred Hitchcock and so many of the great names of sound cinema, Lean grew up with the silent cinema as a young man and started work there. I tried my very best not to do that book—I was about to start in on Griffith. I didn’t have time. But the publisher came back and said, “How about this? David Lean says he likes The Parade’s Gone By. So just do the interviews. He’ll take the transcripts and write his autobiography.” That sounded like fun—sitting with a cup of coffee and listening to wonderful stories. But when I asked David how he was coming on his autobiography, he asked, “What autobiography?” He had no intention of writing it. The publisher had [Sam] Spiegeled us. When I saw Lawrence of Arabia originally, I had the great advantage of being warned against it by my assistant editor at the time, Mamoun Hassan, an Arab who thought it was such a disappointment for historical reasons [and was later a producer on Winstanley and head of the National Film Finance Corporation]. So I went reluctantly and saw undoubtedly one of the greatest films I ever saw in my life. Of his other films, I particularly like the Dickens movies. I remember, after his Great Expectations, the producers made a short promotional film about their talent search for the role of Oliver Twist. My mother put me up for it. She thought: I had the right look for the role, I had done some acting, I had seen an earlier version, and Brownlow was the name of Oliver’s [adoptive] father. But I was never invited to the audition. The boy they did cast, John Howard Davies, was a year ahead of me at my school. He ended up directing at Thames Television when I was there making Hollywood! Stanley Kubrick is another director who was very helpful to you. Oh, Paths of Glory! Imagine walking off the street and into the cinema, expecting to see the usual 1950s run-of-the-mill war film—the British ones were really embarrassing. To see that depiction of the First World War was absolutely staggering. So when Andrew and I went to see a screening of Erich von Stroheim’s The Merry Widow at the National Film Theatre, who should be there but… Kubrick! We introduced ourselves and talked about von Stroheim. He was fascinated. When we told him we were making our own film [It Happened Here], he asked, “How are you doing for raw stock?” We couldn’t believe it. “Not very well!” He said, “Here’s what you do. Monday morning, ring my secretary!” And we got a huge box full of short ends—rolls that are not completely shot. I was afraid we’d get Peter Sellers in double exposure all the way through [laughs], but no, we could use it. And he was very enthusiastic at the end; one of the most enthusiastic people looking at It Happened Here. I wish he’d written it down! I became a telephone friend of his. You know, he’d ring people up from time to time. After he finished Barry Lyndon, he told me that in England he got 17 bad reviews out of 23! Isn’t that amazing? Imagine the amount of effort put into making an ordinary film—that’s tough enough. But to do something on that level and get that response. I just saw a comedy short at the Fastnet Film Festival, Kubrick by Candlelight, about how they were always running out for candles so John Alcott could light the celebrated interiors involving Marisa Berenson that were shot entirely by massed candlelight, stealing them from churches and convents. Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, and a contributor to the Criterion Collection.