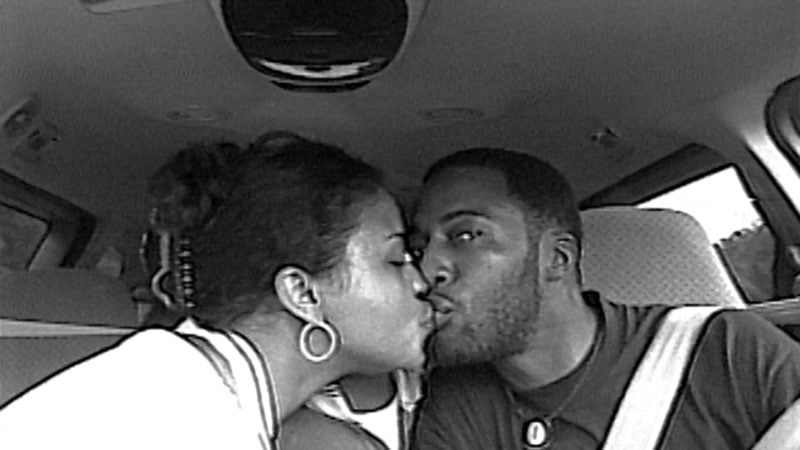

Time (Garrett Bradley, 2020) It’s rare for a consensus to form around a single film at Sundance before the awards are given or the deals announced. But ask anyone during the festival’s concluding days what their favorite film is, and they answer Garrett Bradley’s Time. Bradley was not exactly an unknown when Time was selected for the U.S. Documentary competition this year. Her first feature, Below Dreams, had played in the 2014 Tribeca Film Festival; her short films Alone (2017) and America (2019) had won awards at Sundance. BAM programmer Ashley Clark made America the centerpiece of a 2019 black filmmaking series. But Time takes Bradley’s work to a much higher level. It’s a first-person documentary, but the first-person storyteller is not Bradley, it is rather Fox Rich, a Louisiana mother of six who for 21 years worked ceaselessly to have her husband Robert released from prison where he was serving a 60-year sentence without parole. When Fox and Robert were in their early twenties, out of desperation they tried to rob a bank. Fox received a 13-year sentence and was released in three and a half years. Robert refused a plea deal that his lawyer thought was bad and received a 60-year sentence without possibility of parole. While raising her children alone, and running a business, Fox never stopped believing that her struggle to free her husband would end in success. She kept a video diary of her daily life, in which we see her change from an insecure, young woman into a fierce, patient, and wily fighter against a system of incarceration that is the contemporary form of slavery. Bradley built her film out of Fox’s videotapes, transforming movie diaries into an intimate and epic film, where past and present flow together like memory, all time-bound up in a single purpose—to reunite a family so they can love one another in freedom. I spoke with Bradley at Sundance after the world premiere of Time. Could you explain how you found the amazing hero of Time? It’s sort of a funny thing. I cast my first feature, Below Dreams, on Craigslist. One of the characters in the film was named Desmond, and the person who played him got arrested. I became very close with him and with his girlfriend Aloné. She called to tell me what had happened, and we made a film together about it. She had never dealt with anything like this, and she didn’t know anybody to talk to. So I literally did a Google search to find organizations for women and the first thing that popped up was an organization called FFLIC, which is Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children. And the woman who picked up the phone was the cofounder and director of the organization, Gina Womack, and she said you need to talk to Fox Rich. She’s the person who can give you the best advice. I originally thought that the short film I was making with Aloné was going to be a series of conversations between women, but only 10 seconds of that ended up in the film. But I got to know Fox and she came to trust me from seeing how I worked and from seeing Alone. And so I see Alone and Time as sister films. I would like them to always be together. Had Fox been keeping this video so that she could show her husband Robert everything that happened to the family while he was incarcerated? Yes, and I think it was also therapy for her. And I think part of what I wanted to do at least at the beginning of the film was to show her as a mother—to show the sacrifices a mother makes, and to show also these private moments that she took for herself that many women feel like they don’t have the right to take. And to show that she never had doubt that he would see the tapes. To me, that was incredible. How did you get Fox’s video diary? I thought I was making a short film. On the last day of shooting, I told Fox, “Okay, I’m going into the edit, and I’ll see you in three months.” And she was like, “Oh hold on a second, I have this bag,” and in the bag was 18 years of mini-DV tapes. It was like my worst nightmare and my biggest dream come true. I believe it was almost 100 hours of footage. And I watched all of it. And the short film transitioned into being a feature. You did amazing things with the transfers. It doesn’t look anything like most lo-res format bump-ups. It looks as fragile as memory but at the same time, the outlines of the images are very sharp, as if Fox was drawing her life as well as videotaping it. It looks really beautiful, and it also has a strong sense of physical presence. And then, how was some of the later material shot, where Fox is talking in public? It’s funny because Remington, her oldest, is shooting a lot of that. He was like seven years old when he started, and she would say, “hold it like this”— sometimes you’ll hear her, and that’s why sometimes it’s zooming in to weird places. Other times she’d find someone who was in the audience and have them film it. With America I was dealing with archive and the lack of archive, and so what Fox did was such a beautiful overtaking of creating her own archive. And she was going at that by all means possible. So it was shot by a variety of people, including her son and herself. And that amazing scene where she and Robert make love in the car. They must have really liked you. You hardly see anything, but it is such a triumph. When we were cutting, she was like, “I have a plan for when he gets out,” and I asked, “Well, when it happens, can I be in the car with you?” and she was like “mm-hmm.” I remember what I did was drive in another car behind her and I had Nisa East, who was shooting for me that day, be in the limo with them. I told her to shoot in slow-motion and that if something starts to happen, to get a visual permission from Fox. She told me, “it’s getting real heavy,” and I told her to make eye contact with Fox and get her permission, and she did. That scene could have lasted a long time. Could we talk about the music? I can’t think of another documentary feature that employs music throughout in the way that yours does, and a kind of music that’s totally unexpected—piano music that combines classical with a hint of blues. It doesn’t carry the film but it flows like a current beneath it. The first thing I’ll say is that Emahoy [Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou, who’s on the soundtrack] is a 96-year-old Ethiopian nun who is still alive, and I found her through a YouTube algorithm. I was entranced by her incredible story. She was a prisoner-of-war as an Ethiopian and was on one of the Italian-governed islands. She was trained by a music teacher, which is where the classical Italian elements come from. She has only made one recording of this which was in 1967 to raise money for an orphanage. I like putting music with pictures. When I was thinking musically, I was trying—and some people will hate this—to think what the musical equivalent of a fairytale would be. Because so much of Fox’s experience and story is kind of a fairytale that comes true at the end. There was something about bringing Emahoy’s story together with Fox’s in space that felt very important. It brings the film to another expressive level. I think this has to do with belief. The music conveys that quality: that Fox’s quest for her husband’s release would succeed. His sentence was 60 years without parole? So then how did parole come about? There were several things that happened. Fox took a plea deal and got 13 years and was paroled after three and a half. But they had a lawyer who convinced her husband not to take the initial plea deal. If he had taken it, he would have served 18 years. So the whole premise of the argument that Fox was working on with new lawyers was that they had a bad lawyer and got a bad deal. In addition to racism and being in Louisiana, I consider that that was part of why the original judge decided to give what was essentially a life sentence—a numerical life sentence. Fox always argued that had that not happened, he would have been out by now. But the average person would not have the dedication or the ability to keep working to get him out that Fox had. So this was part of the challenge for me and Gabe Rhodes, who cut the film with me: how do we understand how exceptional this woman is, but not to the extent that people feel alienated by that exceptionalism? So that it still feels universal to other women who are going through this? My audience is black women and black families, and so I hope all of them can find entry points into it. This shows you what is required of a person in order to achieve what she did. There have been a number of documentaries about incarceration being the contemporary form of slavery. But none of them are as emotionally affecting as Time. That the film is such a powerful experience is partly because Fox’s struggle is not abstracted or framed with abstractions. But that goes against the trend in documentaries to have lots of statistics and facts on the screen. When you edited, were there questions about whether you should put information in titles or find other ways to convey basic facts about Fox’s situation? Yes. Time is a co-production between The New York Times and Concordia. It’s the second film I did with the Times. When I made Alone, I didn’t know anyone in the industry. I just submitted an idea on the Times website, and three months later they reached out to me. But with Time, we needed to have a conversation around the distinctions between journalism and documentary filmmaking. Do we need title cards? How do we get the facts in? I am really thankful to them for allowing me to make the decision to not do that. Let’s omit that stuff like titles and let the film be about the human experience. And there is also a problem that exists when you make films like this, when the filmmaker is expected to do an impact campaign. But that is not for me to lead. I feel like that is for Fox to lead. I think she can do it better than I can do it. What I do is I make movies. And she has a cause. I hope that this film can set a new precedent not only for filmmakers but for subjects to have agency in their own story. Amy Taubin is a contributing editor to Film Comment and Artforum.