Monterey Pop When did you decide to become a filmmaker? I lived in quite a different world. I grew up in Chicago, born in 1925. My father was a photographer, a very famous one. In fact, he did a lot of ads for Underwood & Underwood. But I didn’t want to be what he was—he had no time for a family. I never went to film school. I was at engineering school at Yale and trying to figure out how to build a power station in the Permian Basin, which interested me not at all. After six months of working as an engineer I left and started a carpentry shop, because that did interest me. I loved making furniture, I did it for, oh, about 10 years until it appeared I couldn’t keep doing it the way I was doing it, just as an offhand thing. Instead I would have to go and borrow money and start a factory in New Jersey. I had to go and do these things I didn’t really want to do. I was living down on Horatio Street, and one of my roommates, William Gaddis, said, “You have to quit your job because it’s a terrible job and you’re not learning anything. You’re going to run out of juice.” “Well, how will I earn my rent”—which I think for the three of us was $32 a month? He said that’s what you learn, you learn to do that. So I became footloose. I was still trying to be a writer sometimes, and I was painting pictures that I sometimes could sell. There were so many better painters and writers out there. I felt, why bother to do it okay when there are people who know how to do it really well? You’re wasting your time. Then I ran in to Francis Thompson, who needed help, someone who could drive him around and things. And I kind of learned how he made films, and that was enough to make me feel I knew something. But I didn’t. Working with Francis, he taught me what an artist was. Up to then I thought artists were just people who painted pictures. He understood that you committed to something for life. It wasn’t just you did this job because you could make some money or it was a good job or led to a better job. It was something you committed to like a religious cause. That was it—there was never any going back or changing your mind or anything. I worked with Francis over two or three years, N.Y., N.Y. is one that I worked on. I was living on East 17th Street by then. I had set up a projector in a little booth over a phonograph so we could make homemade movies of people in the park and play records to go with them. Kind of a thought. I didn’t do it a lot. So Francis said, Aldous Huxley is coming to my apartment, we’ll use my setup to show N.Y., N.Y. to him there. The music he had on the early cut was this Hungarian composer I had never heard before, Bartók. I had never fucking heard Bartók. When I heard that piano concerto, it just killed me it was so fantastic. He used chunks of it to make the film work. It makes me so sad that music got lost for the final cut. How did you become a filmmaker on your own, with your own visual sense? Well, I needed a camera. There was no camera that would do what I wanted, so you had to make a camera that would.

Daybreak Express But it’s more than just equipment, you developed a distinctive visual style. How did that form You just watch. Just watch. Don’t interpret, don’t explain. I kind of got that idea from [Robert] Flaherty, whom I met once. I never knew him well but I certainly knew his movies. Ricky [Leacock] was his cameraman. The thing I understood about this kind of filming, and I think I also learned it from Flaherty, is that you have to begin from the beginning. Like any story. You can’t get somebody to tell you what happened, and have it work. It loses “storytelling.” With Daybreak Express [1953], I was thinking my way through without even understanding what I was even doing. I didn’t know enough about filmmaking. I didn’t know anything that you’re supposed to know as a director or a cameraman. I didn’t even know what crossing the line was. But I was all alone, no one was going to tell me anything, and I could shoot what I wanted. And I didn’t know how to make, how to create a scene. Back in the 1920s Chicago was exploding with jazz. When I first heard the word, I remember saying something to my father, who I didn’t know very well or saw a lot of him because he was working all the time. He said, “I never want you to use that word in the house.” I thought this is an adult word, a world that I’m going to have access to. When I was 10, my friends and I knew Fats Waller, Louis Armstrong, all those names. I’d never seen pictures of them, and their music couldn’t be played on the radio. We all knew about jazz, we knew it was gigantic, but you couldn’t get to it. Except you could buy the records, buy the 78s, which I did for a dime each. I remember the first four or five records, one of which was Armstrong’s “West End Blues,” which I still think is one of the great records ever, in the history of recordings. I bought all these records, but I didn’t have a thing to play them on. I didn’t dare tell my family, or my father. He had remarried, he had long since left my mother. He had married a young student, and she was totally uninterested in music. He was the only one I worried about and I saw him so little that I knew if I got the records and kept them someplace in my room, they’d be safe. I just felt proud to have them, I had these valuable things that nobody else understood. And I still have them and can play them. There was a school on the West Side, Austin Community Academy High School, and all these kids there wanted to play jazz. If I had spent another year in Chicago instead of being sent back east, I would have gone to Austin High, that would have been my dream. They had a little place where you bought sodas and candy bars and stuff, with a wind-up Victrola. The kids would get ahold of the records of the bands coming in, Joe Oliver or Armstrong, and they sat around listening to the music, trying to learn how to play it. So 10 years later, when Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey had their big bands, a lot of the musicians came from Austin High. Later, when I thought about how jazz influenced me, I realized that I learned how to edit film by listening to those 78 rpm records. When those songs were originally written and played, they were long. “West End Blues” must have been about 20 minutes. But to make any money, to sell records, you had to reduce them to three and a half minutes. It wasn’t a sacrifice or giving anything away, you needed the money. Listening to those 78s taught me how to create scenes from a lot of information when you film with a camera. Because when you’re filming, it’s like a hunt. Anything that moves, you film. If it looks interesting , you film it. And you build this huge collection of stuff you’ve filmed. And then to edit it, it isn’t just cut out the bad pictures. You had to create scenes. I learned what scenes were just by trying to make them. When you were filming, were you creating the scene in your head? I guess I was. I was thinking of where does it go. The essence of a scene for a writer is “Then what happens?” Everything has to build to “Then what happens?” And then you go to the next then what happened. It’s a series of steps, storytelling steps. “Then the first bear said”—you know that from when you heard it as a child. If you cut it too short, what happened to the bear? Because that’s how [where] you react.

Opening in Moscow How did you start working with Albert Maysles? Al [Maysles] and I went to Russia and spent four or five months together. That was where we really started. Opening in Moscow [1959] still gets distributed in Russia. It was all Kodachrome so it looked beautiful. See that little square camera over there? That’s what Al and I used for it. Hand wound. I could get very close to 24 frames a second, but you can’t shoot music with it. A wind would last about three and a half minutes. About half a roll. Anyway, Al and I worked a lot together. In Primary [1960] I set up a shot with Al of Jack Kennedy coming down a line of people at a campaign event. I think it was with an Arriflex. I had this wide-angle lens that was just terrific, very sharp and very fast, and so I said just hold it over his head and follow him. He followed Jack through the back of the room up onto the stage. Everybody loved those shots. I shot with Jackie, I could see her hands shaking, see how hard campaigning was for her. It was scary. By then you had co-founded Drew Associates with Richard Leacock and Life correspondent Robert Drew. Primary became a turning point in documentary filmmaking. It was the synch that really changed documentaries. I helped build the machine Drew used to synch the camera and tape recorder. Because the cable that Drew had to Ricky’s camera shorted. So everything had to be lip synched when we edited. We had to find the synch. Nothing was even cued. So that was a big problem. You listen to the beginning of Primary, you can hear the drifts even though we corrected it as much as we could. That was when Drew saw how important synch was. So I said, “Listen, we’re going to build a camera, and one way or another we’re going to get Life to pay for it. They may not know they’re paying for it, but that’s what’s going to happen.” He said I’m with you. Drew had an office requisition number which was 3333. We put that on every purchase order for three years. They must have put many thousands of dollars into that camera, and they had no idea. But it was so important getting that camera. I had a friend who lived up on Lake George, he had a machine shop in his basement. He used to fly down and take me back in his plane and I could work on weekends in his machine shop. I had taken machine shop at MIT, so I knew how to work all those machines. We needed to have something that you could carry on your shoulder, go anywhere, go backstage, go anywhere, and whatever you shot would be in synch with whoever was taking sound. That’s what it was. The hardest thing was to get an engine to drive it so it could be sync. [Stefan] Kudelski took a great interest in what we were doing. He used to come over and redesign his tape recorder. When we put the crystal clocks in our camera bodies, he puts crystal clocks in the Nagra.

Primary What made you decide to go out on your own? Working with Drew at Life, which I had been doing since 1960 really, Drew kind of let me do whatever I wanted. He couldn’t have been more accommodating in that sense. It was a job that I always felt was the sine qua non job of all jobs. And I was getting paid, I was married and had a child coming. So it seemed like a good place to be. But I began to see it, after Crisis [1963], and I had done two or three films there, one on Jane Fonda and one on the piano player Susan Starr. So on those films, I kind of learned how to do it, how to make a feature. That is, how to extend scenes so that you had a full-length film. Up to then I had been making films but they were short, necessarily. They would accommodate all the pictures I happened to like in one place, what you see. At the time I hardly knew Ricky. We had worked together for Drew, but we had never made a movie together at all. The closest was Crisis, the thing we did with Bobby Kennedy, the students going down to the University of Alabama, and Wallace standing in the door. But I knew who Ricky was, he was a kind of commanding presence in the world of documentary filmmaking. He was also an actual qualified cameraman, I think he had the union card. He worked on Baby Doll as a cameraman. He was something I wasn’t even close to. Several people approached me about doing features in that fashion, the way Ricky did. I was intrigued by it because I could see you would get paid well, and you kind of had a certain control of the thing. Which maybe fooled you. You didn’t ever actually get control, but you thought you were getting it, it looked like you were getting it. I knew Kerouac slightly, we all went to the New School together, and I knew him and Allen [Ginsberg], they were all friends of mine when I was growing up. Kerouac always wanted me to do On the Road, and I kept saying, I don’t know how to make that kind of film, you know? I wish I did but I didn’t. I loved the idea of it. I told him, “If I go with you, can you all get out there on a cold winter’s day and we’ll get a car, I’ll go along with you.” But I didn’t do them. I turned them down. I wanted always to have that control. I’m making these films for Life, but I really want to make one for myself. I want to make a film all by myself, with nobody else doing anything. At that point nobody thought you could make a film by yourself. It took a big studio and a lot of equipment and a lot of people. And I thought of it like a painting or a novel. And Albert [Grossman] understood that. He didn’t know me very well. We never met before he came to the office. But he could sense that about me, how I wanted to control my work. I wanted to tell my own story. So when Albert came and asked me would I want to go England with Dylan and make a film, film him, I was ready.

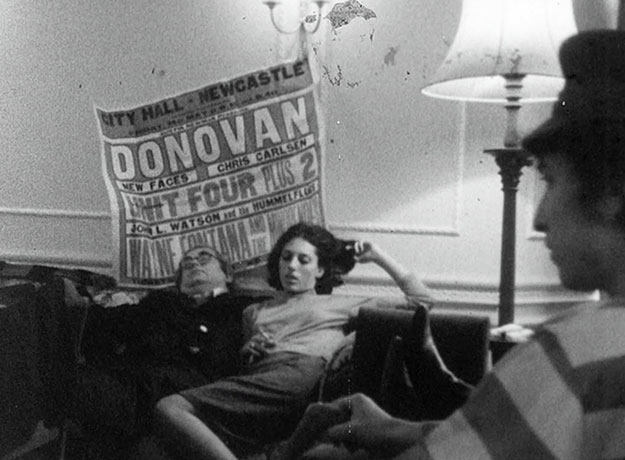

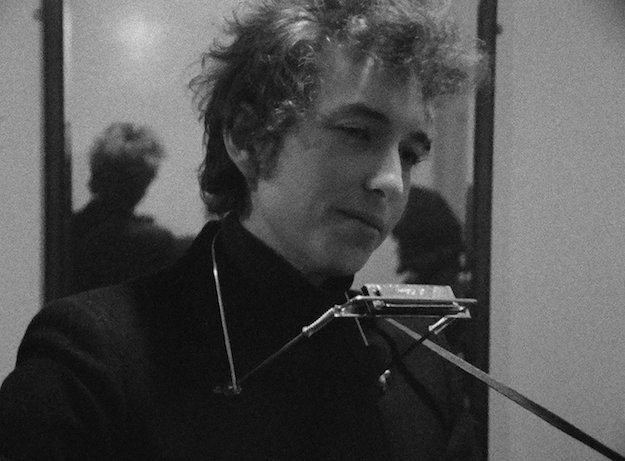

Dont Look Back Grossman was Bob Dylan’s manager. Why do you think he hired you for Dont Look Back [1967]? He didn’t hire me. In fact I paid for the film. He just said come along. Nobody paid me anything. I was told that I could do it. It was as simple as that. I don’t know where Albert knew me from or anything else. I know that Dylan had seen my early film, Daybreak Express. Sara Lownds, the woman he married, had actually worked for us at Drew Associates. I gave her a print I think. He knew about the film. Whether he liked it or didn’t like it, whether he was even involved in the decision to make the film, I didn’t know. I never asked. I think Albert decided to do it because he wanted Dylan to become familiar with being filmed. I think he had a mind of maybe making a deal with Twentieth Century or somebody and making a movie. Albert saw Dylan’s future very clearly, more than anybody else I knew. He saw that he had to be dealt with carefully. That you couldn’t just throw him into a role or put him in a situation. He wouldn’t even let him go on TV. He said, he’s got to be protected. I always respected that. I kind of loved Albert myself, I thought he was interesting. At one point I even asked him to manage me. Which he said was too complicated, he couldn’t do it. I asked Columbia [Records] if they would put up the money for the movie, but they said no. So instead I had a kind of handshake deal with Dylan, we would split whatever profit there was after I made back the money I put into it. Which I never knew how much because of my accounting, but it didn’t cost much because it was just me. I had a guy go along to record the concerts, but I didn’t use much of the concerts. Very little. I didn’t want to make a concert film. Originally I thought that that was what Albert wanted, to help sell the concerts he intended to do in the US. But after the first three or four days, I was much more interested in the way Dylan talked to people around him. I kind of thought this is like the early days of Byron, when he was made head of the theater group in Ireland while he was still a teenager. I thought Dylan’s kind of a poet , and he doesn’t even know that, he doesn’t understand what a poet is. He’s trying to figure out what he is. And that’s such an interesting thing to film. I thought I won’t pay much attention to the music, I’ll just use it when it’s accommodating. Each day I would think, I want to hear him talk about this particular poem, or just lines he would use. There were certain lines in the songs, “ships with tattooed sails”— I wanted to hear him say that, and then hear him talk to people where you kind of heard that kind of language. “She’s true, like ice, like fire,” things like that just knocked me out when I heard them. And I thought since there was no script, I had no producer, nobody to even equivocate with, I could kind of decide these things the way you would if you are writing a book or painting a picture. You decide them on the spot of where you are doing it. Did you have full access to Dylan? Were there times you weren’t supposed to film? Yes, total access. There were moments when you would have been advised not to film by the studio or the people who were recording his music. Because it wasn’t a popular image. Very regressive in a sense. Certain words which generally people were avoiding. Did you know the people around Dylan? I knew who Joan Baez was from her records, but I had never met her. These were fantastic people and I felt really lucky to meet them. Alan Price, I still treasure him. So as you said, you’re sitting in a room with a lot of people and they’re all talking and playing music, a lot of noise. How do you build a scene out of that? Well, part of the process of filming is the downtime of reloading. How I worked, there were these surplus Army bags, I still have some, you could buy them on Canal Street, very cheap, and they held thirteen 300-foot rolls. Actually they were 400-foot, I always called them 300 because you had to figure when you start one and get called off and something would happen and you couldn’t change your film. We took Plus X and would double or triple the speed, but you had to do it for the entire roll. So a lot of times you would switch rolls while there was some unexposed footage left. You switch rolls in a black bag, you put the magazine in there. And that downtime is your listening time, your figuring out time. It’s kind of essential. It gets lost now when you put in a digital card that’ll last six hours. Why turn off? You keep shooting. Why would you not shoot? But then you had to turn off. So what would happen is I would shoot maybe two or three rolls a day. I think maybe 40,000 or 50,000 feet total. I went to a regular lab, told them I was pushing it. Didn’t see any footage until I got home. I never wanted to edit it as I went, I wanted to keep it in my head. Can you talk about your relationship with Dylan? Did it feel like you were collaborating? Was he aware of your presence? Always, always, always was, but he didn’t care. It was a homemade camera. It wasn’t like I was going to be any kind of dangerous filmmaking incursion into his life. There were no lights, no equipment at all except the camera. And that’s all he would ever see. Sometimes I didn’t even have a sound person. I would take a Nagra and put it in the middle of the room and turn it up. Like the stuff where they’re all singing, there’s no sound person there. Dylan was very friendly, we were good pals. We’re still partners. He came over once, several years ago, when we were going to bring out the video, and he wanted to know if we could take out the drunk scenes at the end. And I said, “I can’t touch it.” He sort of understood.

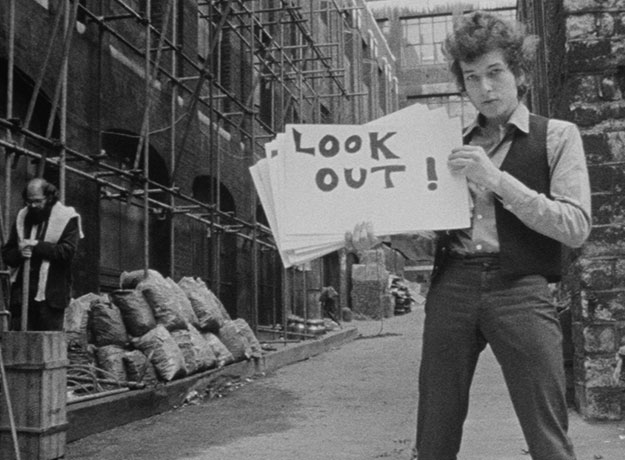

Dont Look Back How did the “Subterranean Homesick Blues” scene come about? We went down to this bar which painters used to go to, it was called the Cedar Tavern. I was told Bob will be there. This is the first time I met him. Bob Neuwirth was with him, they were kind of looking me over. In fact, Dylan thought a woman sitting at the back of the bar might be Lotte Lenya. He was really interested in her, he’d read a book or something. I looked and for a moment I was really fascinated, but I said I don’t think so. And that was almost our total conversation until about, I think we maybe had a beer or something, I don’t know, and he said, “I had an idea of taking paper and writing like chapter headings on them,” holding them up with headings for the song that he had just written. I guess he had just recorded it. I said that was a fantastic idea. So we brought all these shirt cardboards with us to London, I had about a hundred of them, and the last couple of days we sat around and everybody kind of did them. I did some of them myself but I don’t remember which ones I did. We went out and we tried to do it first in the garden back of the hotel and a cop came up and was very upset that we were doing it, was tapping me on the shoulder and I was trying to get rid of him. We said, “This isn’t going to work.” So then we went to the alleyway because nobody cared what we did there. And we just shot one take, I set the Nagra down and turned it on, and Dylan did the things. And Allen was there with Neuwirth and the two of them. I didn’t care what they did, I didn’t care if they were in or out of the film. I just wanted it to be as off the cuff as it could be. Can you talk about editing Dont Look Back? It took three or four weeks to edit. This guy from Chicago, a good filmmaker, he said, “I’ll edit that film for you,” and I remember thinking, “You’ll edit the film for me? Are you kidding?” Why would I have anyone else edit it? Why wouldn’t I edit it? I had a little viewer, that kind with the little screen that got very hot. It cost me $75, you pull the film through it, and I had a synchronizer for it. They had just started to do transfers when we were shooting Primary. So we had to build our own transfer system, they didn’t exist yet. All the sound was on 16 mag, and then you synch it up. Sometimes you had a cue, but a lot of times you just had to find synch, you had to lip read or whatever. You got good at it. You got it all synched up, you could put the things on a rewind, and run the mag track through the synchronizer. The beauty of it was you could pull it through very fast. The sound was terrible. But you already knew the sound, that wasn’t the point. You could change things very quickly. It made editing very simple. Much simpler than a Steenbeck actually. Like for instance I knew a guy who was making a film down in the South, Ed Emshwiller, who had shot Dylan singing “Only a Pawn in Their Game” in Mississippi. But he said, “I can’t use it because I don’t have the rights to it or whatever, but I’m going to send it over to you in case you can use it.” So for a long time it sat on a shelf over where I was working. And I came to the point in the film where a guy asks Dylan, “And how did it all start for you?” I thought, shit I don’t know how it began for him, I don’t know anything about how it began. So I pulled the film down to see what it was like, and I put it on and I never took it off. It was like God had handed it to me especially for that moment. When I started to edit I had this thing I had shot with Bob where he’s doing part of a song, he starts off standing. I thought, that’s where I’ll begin the film. But then I was watching it and I thought, this doesn’t work because nobody knew who the shit he is. Nobody’s ever heard of him really. He’s got to do something that they’ll never forget. So I stuck “Subterranean” on the front of the film, and that was it.

Dont Look Back Did you change anything else in the edit? One time Dylan called me up, and he had seen one of the last work prints that we had, it may have been the final one almost. And there’s a scene where he’s playing the piano, and he’s playing it clunkily because he wanted to hear how it would be when he sang with it. He wasn’t playing it to entertain somebody, to make it smooth. He was banging on it. And I thought, you know, for non-Dylan freaks, that may be a little too much. It was long, so maybe I should edit it. So I cut it down a little bit. So he called me and he said, “It looks pretty good. I just want to ask you a question. Did you ever film anybody writing a song?” And that was all. That was all he said. And I went back and put everything back in. That’s the way he would be. He would never go into discussion about it. It would be a question in his mind of why is it this way. How did you get Dont Look Back into theaters? Distribution of films has always been a complicated and mysterious process for me. I don’t have a hands-on process in the distribution of my films. But it doesn’t matter what I think because they’re all free online. The music gets paid online but not the filmmaker. They might as well be public domain films. I know Dylan’s people have written complaints to remove clips, but two weeks later they’re back on. I feel like a laborer in medieval England or something, I’m just lucky if I get fed. With Dont Look Back I was really in the desert. A porn guy came to see it and he said, “It’s just what I’m looking for, it looks like a porn film and it’s not.” He gave us a big theater in San Francisco and I think we had a 16mm print running there for a year. We went up to San Francisco to see what it was like, Ricky had never seen one before. It had such a grandiose name, I thought it was going to be a wonderful place. When we got there it was so ratty. But there was a line around the block. When I saw that line I went, “Oh boy, this is the right place.” That picture by your desk of the boy under the Coney Island boardwalk, that’s from Little Fugitive by Morris Engel? Morris was doing a different thing, he wanted to make films on his own that would be normal, competitive, commercial films. That would get distribution like a Hollywood film. He spent a lot of time here, we had long talks. Of course he wanted to join a brotherhood that didn’t have any interest in him. Eventually, the last film he made, I Need a Ride to California, which is a fantastic film, in color, I think the Museum of Modern Art has a copy, but I don’t think it ever got finished. But I loved Morris because he could see what I was doing, even though it wasn’t commercial. In the beginning when I came back with Dont Look Back, no one would even look at it, there was no way you could sell it to anybody or get it shown anywhere. Television, you couldn’t even speak to television.

Monterey Pop Your next film was Monterey Pop, which in its way was just as influential as Dont Look Back. It’s a film that couldn’t have been made without those cameras. They tried before, but it’s the first concert film that was synch sound. The one at Newport [Jazz on a Summer’s Day], they had a 35mm camera, but all they could do was stand at the back of the hall and use a long lens and film everybody at once. You couldn’t go onstage with people or get backstage, you couldn’t do anything like that until you got synch cameras. You started working on it before you had figured out what to do with Dont Look Back. Somebody called me up and said, would you like to make a film on a music festival here in California. I said absolutely and that’s how it started. I went out but the guy disappeared. I did meet John and Michelle Phillips, who were in The Mamas and Papas. I got taken in by them, I became part of their family. The business behind it, all I know is that Lou Adler said the musicians are working for free. The first time we went up to see the site, there was no stage or anything, it was like a place where you sell farm animals. I didn’t see how you were going to get a crowd of people to watch. We got a friend to help build the stage, John and Michelle helped, they were workers. I had some cameramen, Ricky, Al, Jim Desmond, Nick Proferes, we were like a gang. And every day we would meet and have breakfast at that pancake house, terrible pancakes, and I would give everybody four or five rolls of film. They’d come back that night and we would send them off to the lab. Before we got home with it, I had seen nothing. I had no idea what other people were shooting. We talked about sometimes, if we had acts, whoever it was, The Who let’s say, we wanted to have stage cameras for close ups. You wanted to be able to get what was taking place on stage. At the same time, you wanted to get some sense of the audience. We weren’t sure what else, we hadn’t seen it yet. We hadn’t seen what would happen. The whole idea of how do you do a concert film, no one had shot one live before. I’m the director right, everybody calls me the director, so I’m supposed to tell six or seven people what to do today. I had no idea what to tell them. How could I know? I didn’t know what I was going to do myself. I sent them off and they were fantastic. I tell you that film made me realize that if you gave people the insight and the liberty to do whatever they wanted, that people who were interested would do fantastic things. There was nobody who came back with stuff that was not usable. I remember I was watching Keith Moon, he’s throwing his drumsticks in the air, and I looked across to the other side of the stage and there was Ricky. So I’m looking right across into his camera. We never used big magazines until Monterey Pop. Jim Desmond used those and Nick Proferes, they were doing stage stuff and I knew that people like Janis were going to sing a long time. If I could stagger those two half-hour magazines, I could cover pretty much anything they did. But I couldn’t do it with 300-footers. You had never seen some of the acts before. How did you determine what to film? I knew Otis [Redding] a little bit because I met in him L.A. I left [Bob] Neuwirth in charge of set lists and I think he just made up which songs. It didn’t matter, we just wanted everybody to be shooting the same song so we could edit it. We had a light on the end of a stick, a red light, Neuwirth was in charge of that. When the light was on, that was the song that we were going to try to film. We were trying to save film, so we would have one song for each group. But people like Hendrix would get on, and nobody would stop shooting no matter if the light was on or off. Everybody shot everything he did. The same with The Who and with Janis. We ended up shooting an awful lot of material that no one had planned on shooting. I didn’t know who Ravi Shankar was. I heard his music, I thought it was pretty interesting, so I sent Jim and Nick to film it. And when I went down to the stage there, those two guys were so hot on the guys playing, I thought they don’t need any help, so I’ll just film the front row of the audience. I think it’s one of the most dynamic examples you could ever see of two guys shooting together, not just each of them filming something, they’re also watching what the other one’s doing. Making it work as a kind of choreography. Also, what you don’t see in most concerts happened here. Musicians would play and then go sit down and watch other people play. It was like a village gathering rather than a moneymaking thing. Standing on the stage and looking out, what I saw was this blending of San Francisco and Los Angeles watching each other’s music and being interested in it, wanting to like it. It was amazing to me. Everything was on the edge of something new. Suddenly there was this sense that a whole new music was being born. But you had to structure all that material. There were so many musicians that in the end editing down was hard. People I knew and liked personally, we had to say no. We made a version in which I had The Electric Flag with Michael Bloomfield in it. Truman Capote said, “That’s tacky.” I thought what the fuck do you know. But the next morning I came in and looked at it and I thought there was something about it. We played it somewhere and I thought Truman was right, I was right to take them out. It’s a better film without them, even though they’re terrific. I was thinking about how to fashion it, what kind of film to make about it. The big thing about festival films, especially where there were hippies and things, was you’d have a little sociology thrown in. Somebody would do an interview on drugs or about being a hippie, whatever it was. So you had to deal with sociology between songs. I wanted the whole thing to be like putting on a record. Put on a record, you listen, and when it’s done put on another record. And nobody talks to you about drugs or any shit like that. And I wanted to have quality. People were worried about that. People who normally would have helped us with distribution thought we were too slick, too I don’t know. Anyway there was a problem there. You first thought Monterey Pop would play on TV? We didn’t have a distributor or producer. Originally I thought that Lou Adler was paying me to do it. Eventually I thought he was going to pay us to process the film, synch it up, and edit it, that we were going to be paid for that. Then I was told that someone had run off with the money. So he couldn’t pay us. We were trying to get our money back. We lost a lot of money. The film bill was huge. And we owed about 80 grand just to the lab. That’s why I was hiring waitresses from Max’s Kansas City to come up and be editors. They were terrific. ABC had given a lot of money, and they thought at one point they could use the film on the air. And the guy from ABC came and he said, “There’s a guy on the front of the stage and he’s not looking through his camera, he’s looking at the tits of the woman next to him. Are you happy with that?” It was Al of course, Al Maysles, and I said, “I’m very happy with that.” So they went away very discouraged. And later, when ABC execs came to look at the film, I showed them the Jimi Hendrix stuff. He’s humping the speakers, and they said, “Not for us.” That’s why we got to own that film. Because nobody else wanted it. I had some friends who had come down from Yale with me, they had jobs at big law firms. I said, “We’re stuck, we owe a lot of money, we’re trying to raise it.” They figured out how we could own it. Then we could raise money, then we had some talks where do you think this could play in theaters, because we knew it wasn’t going to be on TV. Everything kind of took care of itself with that film. Which it hadn’t with Dont Look Back. Life gave a good review. Half the things that happened to me, that I look back on and were really good, were all kind of I think of as luck. Chance. That a lot of people could have had the same luck, they could have done it before me.

The War Room You talk about chance or luck, but one of the keys to your work is getting your subjects to trust you. How do you earn that trust? The secret of this kind of filmmaking is, you get taken into a family. When we were starting The War Room [1993], first of all I was very uncertain about that project. I don’t think it’s possible to make a film about a person running for president. You can follow him, you can be with him a lot, but basically what you’re doing is a home movie, while he’s got the six o’clock news to worry about. That’s so much more important than whatever you think you’re doing. No matter how much money is involved, you’re not going to get anything that’s worth anything. But if you make a film about James… I didn’t know this at the time, but James Carville had been put in charge of the whole thing by Hillary. He was kind of a major figure, but you’d never knew that by listening to him. We had gone to George [Stephanopoulos], and he said, “I’ve got this group from Newsweek following us around, and I can’t get you into that, it’s too hard.” And I was kind of happy with that. I didn’t think it was a good place for us to make a film anyway. But I thought maybe we can make a film with you and James. We [Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus] had met James in the hotel, and we felt maybe he was somebody’s drunken uncle, he seemed so totally out of it. He was the only interesting person we filmed when we started the thing. So George said, “Go down to Little Rock and if he says it’s okay I guess it’s okay. The Governor isn’t going to care.” We went down there into that huge basketball-court-sized office with the beer and popcorn. When we first went there he had these little things on his face, like blemishes, like throw-up some of them. And I said to Chris, “What’s wrong with his face?” And she said, “It’s bubble gum.” He was chewing bubble gum and when he’d blow the bubble would explode on his face. Does cinema verité require that we tell somebody that he had bubble gum on his face so he’d clean it off or does he have to figure it out for himself? We decided he had to figure it out for himself. We didn’t really film him much that day. He asked what we wanted to do and I said, “We’d just like to come down and hang out here until the election and just watch what happens. We’re not going to interview anybody or anything.” So he asked, “Why should I let you do that?” And the only answer when someone asks you that question is, because you want to. So he said, well, I have to think about it. So we went to our motel and waited. About an hour later he said okay. And that was it. You know he liked Chris, they liked Chris, they liked the fact that we were a couple, clearly a devoted couple. They took us into the family as if we’d been hired by the people who ran the election. From then on we did anything we wanted. We ate lunch with them, we never left them. How do you respond today to your political films? You know, when I was filming Bobby Kennedy, there’s a moment when he was singing Christmas carols, when he looks right at me, he stops talking to the kids. Later I said, “You were thinking of the assassination,” and he said, “Yeah.” When he got himself killed, I was supposed to have been there. The thought that I might have filmed him getting killed just filled me with such despair that I almost gave up filmmaking.

Unlocking the Cage But with your recent films like Unlocking the Cage [2016] you’re still fighting. But these things, we don’t cook them up, they kind of come to us. They’re like little chickens who know we have a warm nest. Almost all of these films have come through the front door. I feel like maybe I should be doing more. I mean I look at Michael Moore as my pastor, he’s the guy who knows right from wrong. In this world he knows right from wrong, and he’s never wrong. I just love him. I just love him. I feel maybe he’s risking his life. He could be put away any day by people who don’t like what he’s saying. And I think I should be doing something like that but I don’t know how to do that. It’s not my plate. You have a vision of society and how it works that I believe in, that I hope comes to fruition. It’s so interesting what’s going to happen in the next year, that you’re almost happy that Trump happened. You’re going to watch a show that you normally would never get to see. It’s just hard on certain people, I know. It’s turned so totally around, that’s what’s interesting about it. It’s a kind of a theatrical gesture on the part of fate to not only have the Republicans get the President but to get everything else in sight. They feel they can’t miss, and that’s going to make them miss. You need to be Napoleon to understand, and they’re not. You know what they call Trump in the White House? “Baby.” Daniel Eagan is a critic and film historian living in New York City. He is currently working on the third volume of America’s Film Legacy, a survey of the National Film Registry.