Throughout his work, Wajda was no stranger to allegory, so often a necessity, as he sought to evade the censors. What today seems like a blunt device was in Wajda’s hands a powerful tool—a way to smuggle in secret portents. In Kanal, which details the deaths of resistance soldiers during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, the city’s waste canals—actually a studio set constructed to maximize claustrophobia and dramatic black-and-white chiaroscuro—evoke the Inferno. The inverted Christ on a cross that hangs upside down in Ashes and Diamonds signals the lost innocence of youth, wagered and lost against the cynicism of the apparatchiks and the military. In the fiercely political Man of Marble, the fallen colossal sculpture of a record-setting worker, stowed away and forgotten, is a potent reminder of how the Socialist system exploited human potential and the public’s goodwill for its own propagandistic ends. Similarly, early in Wajda’s final film, Afterimage, a giant banner bearing Stalin’s portrait is hung on the façade of a building that houses the studio of its artist protagonist, Wladyslaw Strzeminski. The canvas blocks the artist’s window and colors his walls red—an omen of the suffocation that awaits Poland under Stalinist rule.

Afterimage Afterimage, which receives its U.S. theatrical release in May, points to Wajda’s lasting fascination with the role of the artist as one who speaks truth to power. The film follows the life of Strzeminski—a handicapped avant-garde artist and influential art theorist who died in 1952—through the prism of his dogged, Sisyphean struggle against the Communist regime, which waged a relentless war on abstract art in favor of socialist realism. And while it may not belong in the pantheon of Wajda’s greatest cinematic achievements, Afterimage nevertheless elicits deep affection for the creative minds that paid for their rebellion with years of humiliation, persecution and isolation. Those familiar with Wajda’s filmography will recognize in Strzeminski’s fragility and physical degradation an echo of the famous trash-heap death scene in Ashes and Diamonds. A scene, in which Strzeminski, after being cast out of the academy, denied his food rations and right to purchasing materials in state art shops, is reduced to dressing store windows, and collapses, amidst half-dressed, pallidly gleaming mannequins, is one of the film’s most chilling. Boguslaw Linda, cast as Strzeminski, even recalls the brooding charisma of star Zbigniew Cybulski in Ashes and Diamonds. Wajda’s most successful productions married their allegorical images to rich psychological insights that often ran counter to the official storyline. In Kanal, Wajda presented the Poles’ wartime sacrifice as tragic yet absurd, given the Nazis’ irrefutable advantage. Innocent Sorcerers (1960), Wajda’s brief foray into the aesthetics of the French New Wave, with a script by young Jerzy Skolimowski, was an uncompromising look at the dissolution, and disenchantment, of the country’s youth in the 1960s. Without Anesthesia (1978), while exploring a familiar theme of censorship and the individual, borrows from Wajda’s personal life to create one of his most intimate films, in which marital conflict deepens the political drama. By comparison, Afterimage, is fairly conventional. Wajda nevertheless finds the right emotional key, by subtly shifting some of the dramatic focus from Strzeminski to his young daughter, as his personal caretaker. As in Man of Steel, Wajda reserves his cautious optimism in Afterimage for the young: Strzeminski’s generation may be sacrificed, but his daughter’s mental sturdiness sows the seeds for a future rebellion. I interviewed Wajda via email last September, shortly before his death, while curating a major retrospective of his work in Brazil. A tribute to the filmmaker runs from February 9 to 16 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Afterimage You have wanted to tell the story of Strzeminski’s life for many years. What was the key to finally filming it? The film presents a reality in which a distinctive artist takes on the system in a heroic, uncompromising way. This harsh reality has been unfamiliar to us for quite some time. But perhaps now is precisely the moment to remind ourselves what those times were like. What was your personal experience with censorship in your earlier films, starting with the war trilogy, Generation, Kanal, and Ashes and Diamonds? Even though in communist Poland we lived under harsh censorship, we had a certain advantage: we knew the war from personal experience. So the regime’s propaganda, which often distorted the truth about the war to serve its own ends, could not manipulate our vision of it. We wanted others to remember that we fought in the Polish army, alongside our allies, for a different Poland. At that time, the Polish army was the fourth-largest force on the Western front. Was censorship also the reason for your turning to literary classics? During the time of harsh political censorship, the classics, especially the older ones, helped us outsmart the censors. They also gave us an opportunity to communicate with our audience, who knew how to read between the lines, and to decipher the metaphors, filled with hidden meaning. You put modern Polish cinema on the map. But by the time you made Innocent Sorcerers, the style of Polish cinema had changed. My realism [in the 1950s] was inspired by Italian Neorealism. But the new spirit of cinema was about expressing the forces that inspired the New Waves in the West, such as jazz in the United States, or the new social behaviors and fashions that we observed around us. It was a look that reflected our inner freedom.

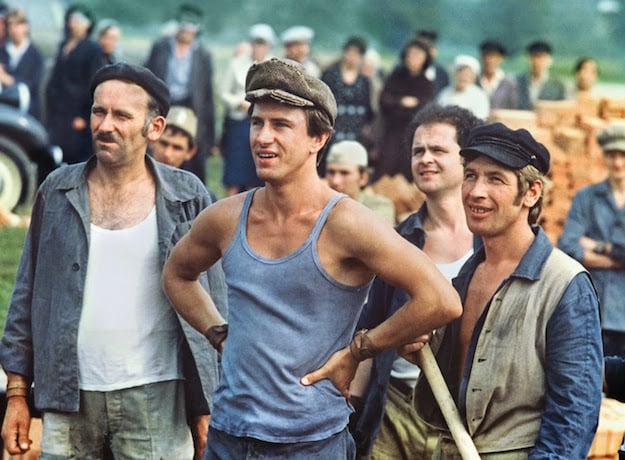

Man of Marble The Communist regime refused to approve production of Man of Marble for a long time. What was it afraid of? In Poland, the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) ruled in the name of the people. It expected everyone to live according to its agenda. But in my film, for the very first time, a worker demands and defends his own rights. That was what the regime feared the most, and why they held back my screenplay for 13 years, not permitting me to make the movie. Of course, later, [in 1980], the independent union, Solidarity, was born out of the same sense of protest. You continued the themes of political and social oppression in Without Anesthesia, which became known as part of the “cinema of moral concern.” Filmmakers Krzysztof Zanussi, Krzysztof Kieślowski, and Agnieszka Holland were also part of this movement. What lay behind its power? The name “cinema of moral concern” came from a group of the young filmmakers that I was guiding at that time. In some ways, these filmmakers were more conscious of our country’s situation than I was. They saw what was happening around them and disagreed with it. And that is what they wanted to express in their films. By filming Without Anesthesia, from a terrific screenplay by Agnieszka Holland, I was basically following in their footsteps. Man of Iron was your only “commissioned” film. What new risks did you take in it? It’s true. I made Man of Iron at the request of a worker at the Gdańsk Shipyard, who got me into the meetings of the Strike Committee. He told me: “Why don’t you make a film about us?” “What sort of film?” I asked. “Man of Iron,” he said [thus suggesting a title]. My main challenge was to make the film before the military police, which was ordered to “pacify” the Solidarity union, took over the Shipyards. I did it. And thanks to the intervention on my behalf by the people who oversaw the Polish film industry, I was even allowed to show my film in Cannes, where it won the Palme d’Or.

Man of Iron The Wajda Master Film School that you founded in Warsaw in 2001 has contributed to the rejuvenation of Polish cinema. What lesson do you hope that young directors learn from your films? I hope that they will learn that we have survived much worse times than our present one. As for the rest, they must draw lessons from the world around them. There is no other way—they have to learn to make films about themselves, addressed to their contemporaries. You always stress that all your cinema, even historical period pieces, delivers a contemporary political message. In democratic times, do you think we have lost our appetite for political dramas? The appetite for political cinema always grows wherever there is a great desire for truth and a need to voice one’s protest or discontent. No doubt, our sociopolitical reality will soon prove whether we are again facing such a moment. Portions of this interview first appeared in Portuguese in Folha de São Paulo. Ela Bittencourt works as a critic and curator in the U.S. and Brazil and is a member of the selection committee for It’s All True International Documentary Film Festival in São Paulo.