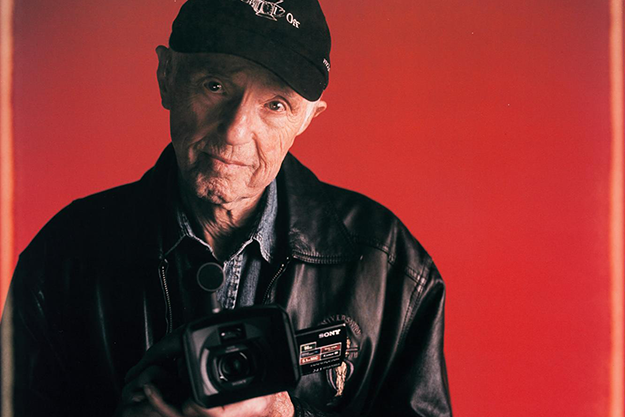

The argument heightens to a mortifying degree, until at last all the pieces of Haskell Wexler fall into place: the political firebrand who vented to his family at length about the failings of government, the virtuoso cameraman and sometime filmmaker who clashed during several high-profile assignments (notably The Conversation and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), and the resolute octogenarian about whom longtime friend Jane Fonda muses, “I can’t believe how not mellowed he seems.”

The Conversation The son of a prosperous electronics manufacturer, Wexler eschewed his class early on, siding with the disenfranchised and dispossessed (in this regard, Dennis Hopper likened him to Diego Rivera). He published a weekly newsletter called Against Everything and later organized a strike in his father’s factory. With family money he established a studio for production of nonfiction films that allowed him to experiment with the vérité techniques which would become his calling card and with the vantage point of the cinematographer: “being there and not being there at the same time.” His reputation for spontaneous, realistic compositions preceded him when he transitioned to narrative features—so much so that Richard Burton despaired of working with him on Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (66), fearing he would highlight the star’s age and acne scars in extreme, unflattering close-ups. Yet Wexler’s vérité training gives the film a cinematic urgency lacking in most stage adaptations, and Burton’s pockmarked face conveys as much about the shattered, dissipated George as Albee’s dialogue. The collaboration won Wexler his first Academy Award—the last trophy awarded for black-and-white photography.

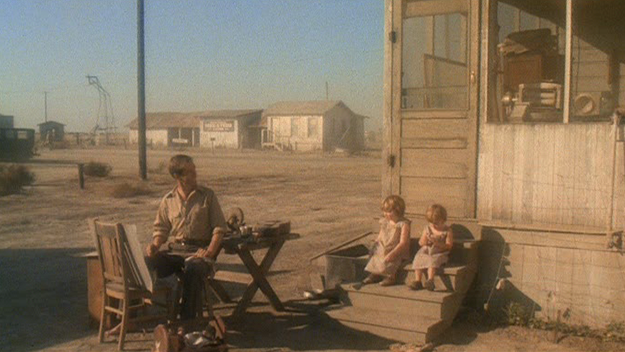

Bound for Glory His innovations in his field make him as much a key player of the New Hollywood as the directors with whom he collaborated (and clashed): Hal Ashby, Milos Forman, and Terrence Malick among them. He enabled Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night (67) to transcend its police procedural template, imbuing it with the sweltering atmosphere of the deep south and an expansive, near-to-the-ground affect achieved quite literally by mounting a tiny handheld camera with a widescreen lens to two-by-four boards and chasing the actor playing the fugitive through the bushes at the height of a dog. Nine years later on Ashby’s Bound for Glory, he incorporated the first Steadicam footage into a Hollywood film, winning his second Academy Award and revealing the potential for tracking shots with unprecedented fluidity. “Controversy is the fertilizer of democracy,” Wexler once said. His 1985 agitprop Latino placed his actors in the fray of the Nicaraguan Contra wars, which he framed as the next Vietnam, filming guerrilla-style as his extras fired live ammunition. Perhaps his most like-minded colleague was director John Sayles, with whom he worked on four features including Matewan (87), a gritty account of a coal miners strike in 1920s West Virginia. And there is no more valuable time capsule of urban, radicalized America in the late Sixties than Wexler’s Medium Cool. Its profoundly personal account of a cameraman who documents the lives of marginalized people and suspects he is being persecuted by the FBI (later Wexler’s theory for why he was fired from Cuckoo’s Nest) climaxes with authentic footage of actors Robert Forster and Verna Bloom at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Wexler’s native Chicago, incorporating Neorealism and documentary techniques into one of the era’s defining hybrids.

Medium Cool At one point Wexler appears on-screen as a tear-gas victim; an assistant director can be heard to say “Look out, Haskell, it’s real!” When later accused of starting the riot for the sake of his film, he mused that he only wished he had that capability. The film ends with the cameraman’s burning car being photographed by a child with a flash camera, who is in turn being filmed by Wexler. “Everybody is in somebody’s movie,” he asserted. “Don’t necessarily believe me, because there’s always another level of reality.”