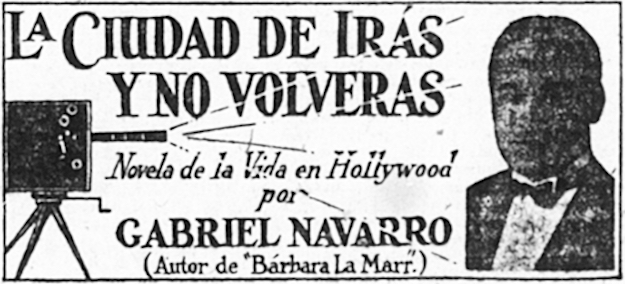

(Courtesy of Laura Isabel Serna) While diversifying contemporary mainstream criticism is an important goal, the history of the parallel stream of Latino or Spanish-language criticism awaits writing. Our new project gathers translated motion-picture fiction—novels that in some way took up the world of Hollywood and filmmaking—and critical writing about films and film culture by a journalist named Gabriel Navarro (1894-1950) who was active in Los Angeles during the 1920s and ’30s. Through the publication of a representative sample of his work in translation, we present a new perspective on Hollywood history and offer a glimpse of an early form of Latina/o media criticism, activism, and advocacy. During the first decades of the 20th century, a uniquely Mexican-American entertainment culture flourished across the southwestern United States. From thriving cities to smaller towns, theaters serving immigrant audiences hosted live musical concerts, films of various origins, theatrical performances, touring performers—singers, musicians, comedians, and others— from Latin America and Spain, radio broadcasts, and community events. This vibrant entertainment culture also converged in the pages of a prolific immigrant press; newspapers like San Antonio’s La Prensa and La Opinión of Los Angeles regularly offered readers theater listings, coverage of their favorite performers, cultural criticism, and sometimes fiction that focused on entertainment culture. The evidence found in these newspapers demonstrates that there was considerable excitement about these cultural forms and the possibilities for new social relationships or forms of expression they promised. They also helped readers navigate this cultural landscape as Mexican immigrants: individuals whose status and sense of belonging in the United States was contested and in flux. Gabriel Navarro was a key figure in this journalistic milieu. Originally from Mexico, the multi-talented and prolific Navarro was a composer, playwright, cultural critic, Hollywood consultant, activist, and author. As entertainment editor for La Prensa and then La Opinión, his writing on cinema and theater was distributed widely across the Southwest. In film reviews, fiction, and interviews, Navarro considered questions of cultural value, fandom, stardom, cinematic representation, and film industry politics in light of changing conceptions of Mexican identity and community in the United States. The volume we are working on, which will be published by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, brings together three short novels written by Navarro during the 1920s, each centered on a different aspect of Hollywood and the film culture that emerged in the Mexican immigrant community: the romantic fiction La señorita Estela [Miss Estela] (1925) a cautionary tale about a Mexican journalist and poet navigating the hypocrisy and deception of Los Angeles; a biography, Barbara La Marr (1926), about the tragic life of a silent film actress who died in 1926; and the serialized novel La ciudad de irás y no volverás [The City of No Return] (1926-7), which traces the fate of a young Mexican woman trying and failing to make her way in silent-era Hollywood. These texts have not been available in print since their initial publication and never before translated into English. In addition to the novels, the book will include a co-written introductory essay that situates Navarro in the context of ethnic Mexican cultural life in the Southwest, a biographical overview of Navarro, translations of selected cultural criticism written by Navarro and published in La Prensa and La Opinión, and a number of images from archival and family collections.

Barbara La Marr, subject of a biography by Gabriel Navarro Navarro’s writings give voice to a paradoxical, ambivalent, and critical perspective on Hollywood as an institution and Los Angeles as a place. An almost nihilistic pessimism pervades all of his literary works. His novels clearly resonate with the observations of other sojourners to Hollywood from Latin America and elsewhere, from Mexican journalist Carlos Noriega Hope to French poet Blaise Cendrars, who found deception and squalor behind the dream factory’s glamorous façade. In Navarro’s case, he seems particularly troubled by the potential impact of Los Angeles on women traveling there in search of stardom and anxious about the film industry’s effect on the sanctity of Mexican womanhood. Each of the novels portrays Los Angeles and Hollywood as an all-corrupting environment that damages everyone in its orbit and threatens the supposed bedrocks of Mexican community: family, heterosexual relations, individual morality, and cultural integrity. While Navarro’s published cultural criticism—including interviews, editorials, film reviews, and gossip columns—sometimes adopted a similarly critical stance, as an entertainment correspondent for widely distributed newspapers he was also arguably responsible for cultivating Mexican identification with Hollywood and its stars. He gradually worked through this paradox by forging a nascent form of media advocacy, expressing enthusiasm for Mexican-origin stars working for the studios while also using his columns to give voice to a marginalized community—aspiring Mexican actors—and to advocate for structural change within the studio system. During the transition to sound, for instance, Navarro operated as a sort of critical liaison between the industry and his readership, pressuring producers to consider the tastes and sensibilities of Latina/o audiences while advocating for a greater Mexican presence in the industry. Taken cumulatively, his impressive yet nearly forgotten body of work tells us a great deal about how historically marginalized populations engaged with Hollywood and other culture industries long before #oscarssowhite. Navarro’s negotiated stance—one that he surely shared with many of his readers—undermines simplified conceptions of Hollywood as imposed cultural imperialism or of marginalized spectators as either resistant or submissive subjects. As was the case with the tremendous African American mobilization around Birth of a Nation in the teens, ethnic Mexican audiences and critics worked to change representational practices in Hollywood. Navarro, for example, proposed that studio hiring and labor practices could affect what ended up on screen. His work allows contemporary readers to more fully appreciate the diversity of Mexican immigrant entertainment culture during the pivotal decades when the Mexican population in the U.S. would grow to an estimated 1.5 million, to gauge the potential meanings these cultural forms may have had for Mexican-American audiences and performers alike. Our research reveals how this immigrant population navigated a period of tremendous social change and began rethinking the terms of identity and community in conversation with mass culture. In Navarro’s writing we see the initial glimmers of the building of communities and markets beyond boundaries of nationality and the creation of a collective Latina/o identity forged in part through a unique relationship to film culture. Laura Isabel Serna is Associate Professor in the Division of Cinema and Media Studies in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. Her webpage is lauraisabelserna.com and she can be reached at [email protected]. Colin Gunckel is Associate Professor of screen arts and cultures, American culture, and Latina/o Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. His webpage is here and he can be reached at [email protected]. Their forthcoming volume of Gabriel Navarro’s writings will be published by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press.