Ernie Gehr has an intimate relationship with the moving image. Like no other artist, the 76-year-old filmmaker has balanced his own poetic and autobiographical impulses with a careful and detailed exploration of what makes the moving-image medium uniquely its own. These impulses have been part of Gehr’s art since his earliest 16mm works (preceded by 8mm works which in Gehr’s own estimation owe much to the work of Stan Brakhage). In Wait (1968) and Morning (1968), the camera is taken through an exhaustive series of exposures that capture a window and a pair of Gehr’s close friends respectively, and we see just what light can do to the plasticity of the image and how it correlates to the illusion of motion; in History (1970), the camera’s lens is dispensed with altogether, the film’s naked emulsion creating the work’s dense, abstract imagery. The more the material of film illusion is laid bare, the more human the endeavor seems, and the more evident the symbiosis between moving image technologies and the human desires they enable. Gehr’s is a cinematic double life: at once mechanically obsessed and philosophically expansive.

After leaving his military service in the mid-1960s, Gehr, a Milwaukee native, found his way to New York City. This would be the filmmaker’s home and a key inspiration until his relocation to San Francisco in the early ’90s. Gehr’s work and that of some of his contemporaries came to be called (for better or worse) Structuralist. These frequently austere and radically formal films are usually viewed as devoid of the stories typical of mainstream movies, taking instead as their subject their own construction and material existence. Gehr’s work, while arguably the most austere and radical of the bunch, does tell a story. Reverberation (1969), History, and Eureka (1974) tell the story of the moving image from the inside, revealing the instant the static image becomes the moving image—its point of highest drama. The ultimate expression of this drama of motion in a state of becoming is 1970’s Serene Velocity—a film in which Gehr interpolates himself into the mechanical process of moving image making, using single frames shot at varying focal lengths, each adjusted by hand by Gehr himself, to create from scratch the illusion of motion.

Gehr seeks the complete humanizing of the medium by transgressing the mechanical boundaries that have historically hidden the true nature of the film experience from the viewer. As our world of iPhones and user friendly apps obscure their own technical realities, Gehr’s desire to peer inside and see how the “magic” is made becomes even more relevant. It’s no surprise that his films are enjoying bicoastal revivals (San Francisco’s Pacific Film Archives and New York’s Anthology Film Archives) and renewed interest as technologies are grafted onto our consciousnesses with a speed hitherto unparalleled in human history–moving images and smoothly self-contained interfaces becoming ubiquitous, more real than reality itself. Beautiful and reflexive works such as Gehr’s however, offer a way of seeing and understanding outside of media’s totalizing horizon by reversing the historically analogous relationship between camera and eye. His work, rather than using machines to re-create human vision and excavate fantastical scenarios from our unconscious, allows viewers to see and understand as a camera does. The closer Gehr’s work brings us to the threshold of the illusion of motion, the clearer it becomes that the camera is simply a collection of hammered metal and molded plastic. The real technology that permits the phantasmagoria of cinema lies within the viewers themselves.

For Film Comment, Gehr was gracious enough to answer a few questions at his home in Brooklyn regarding the restoration of his film History as well questions about other early works, making films in New York (and his circle of filmmaking friends), painting, and the moving image’s unique character. His Essex Street quartet is part of MoMA’s Gallery Sessions: Artists in Mid to Late Career.

Still

You have been working with the Museum of Modern Art on the restoration of your 1970 film History. What is it like to approach a film that you made many years ago again? Any challenges in restoring such a visually unique and graphically dense work?

I don’t quite know yet. Recently we went from 16mm to digital. The next step is going from digital to 35mm film. I hope that works. The reason for this convoluted and expensive process is that we tried to go from film to film in the mid-1980s when Jon Gartenberg was still a preservation curator at MoMA. The results were totally unsatisfactory. The image was just too dense. We could not make a reasonable film preservation master. This time, going through digital, we hope it will work. It obviously will not be the same as going from film to film, but hopefully close.

Each restoration has its own idiosyncratic character. One can bring a work back to life, or if one is not responsive to the internal dynamics of the work, mess it up. For example, History was originally a sound film projected at 24 fps. Even after showing it as a silent work, it was still projected at 24 fps. However, to prevent the sound print being projected with its sound track, at some point I opted for silent speed projection. At the time I thought that the image at that speed was acceptable. Looking at the work now, especially the way digital works, History at that speed did not look or feel right. So my decision is to return to the original intended speed of 24 fps.

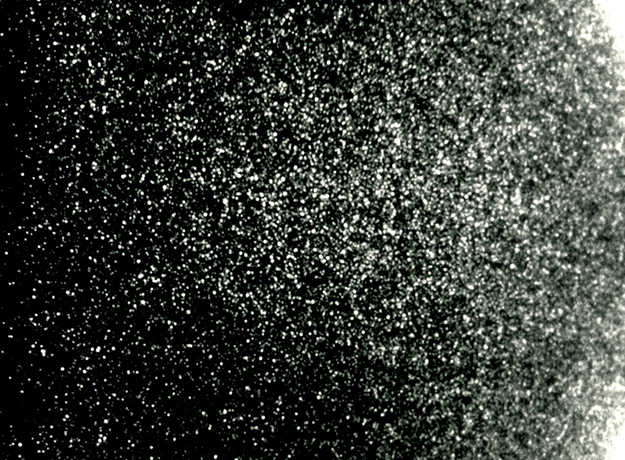

For History you employed a cheese-cloth and dispensed with the camera’s lens all together. Where did the idea come from? Was this your first and most intense reckoning with the materiality of film up to that point?

I just cannot remember how I eventually arrived at the final image. There were definitely several different attempts. History was preceded by four other works: Morning, Wait, Reverberation, and Transparency [1969]. History relates closely to Morning and Wait. The dynamics of film emulsion responding to light were part of a focal point in Morning and Wait. History is a return to that photographic emulsion. But instead of its activation by light in the process of forming an image, in History the focus is on the grain itself, and the pulsing, wildly intoxicated “animation/dance” they create or allude to as their composition changes from frame to frame. This also affirms a time without past or future, just the present.

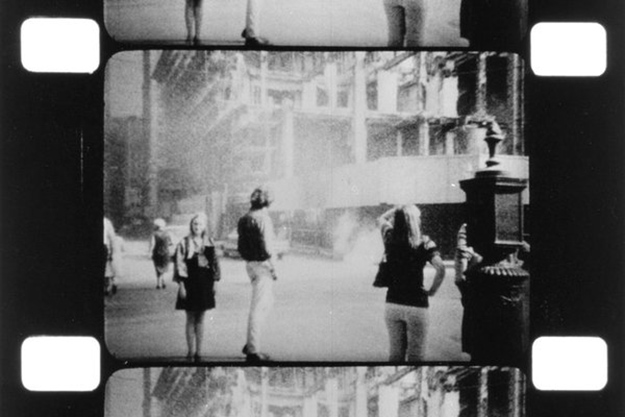

You mention that Reverberation preceded History. This work, more than Morning and Wait (which were made roughly concurrently), seems to approach the foregrounding of materiality found in History. Can you talk about the “degraded” quality of Reverberation, focusing on the film’s grain, and the soundtrack, which was also an attempt to foreground the surface noise of the recording?

To some degree the work is a kind of home movie of two friends posing for the camera in front of three settings. The first one is in front of the demolition of a building; the second one on a corner in front of a cemetery, with a subway entrance to the side of it; and the third takes place in front of a huge stone wall that on film I tended to read as a scale of grey tones. This footage was then re-filmed, going from 8mm to 16mm, and using an 8mm projector I had previously tampered with. The film pull-down claw was partially cut off, and the pressure plate loosened so that the registration of the film in the gate was uneven and sometimes a bit jerky.

One thing I was after was making the film bounce erratically in the gate of the projector, bringing attention to the intermittent projection of still images. To make this process more emphatic, the 8mm film was projected at 5 fps rather then 18 fps, and recorded onto 16mm at 24 fps (later to be projected at 18 fps). Later on, looking at the re-filmed 16mm footage, to my delight I discovered that in contrast to the deteriorated look of the film, the features and persona of Andrew and Margaret still radiated with power and energy, offering a kind of transcendence of the human spirit over the machine and the chemical character of film.

For the sound I started with a piece of music on an old, grainy, and scratched-up record. I placed a microphone right next to a speaker cone, began to play the record, and then began to make changes until I was able to get rid of most of the music and was able to record mostly noise and the speaker cone reverberations. What I was after was a sound equivalent to the re-recorded image quality.

Side/Walk/Shuttle

Reverberation, with its ghostly, halting tempo and images is a film that is both very much about the past (documenting a disappearing New York and even the film’s stylized “aged” quality) and the present (showing your friend, the late Andrew Noren, young and in love, while the projector is manipulated to disrupt the film’s speed and movement, creating a constant present). Can you talk about this dual nature of the moving image as document of the past and an always-present illusion created each time it is projected?

First of all, I much enjoyed looking at the mechanical process of the projector seeming erratic in its registration of the film image, like bouncing within the gate. When I began to make films, I often came across 8mm and 16mm projectors that had problems of one kind or another, and of course that was often frustrating. Occasionally even nerve racking. But in the process of thinking and considering the character of these cheaply designed cameras and projectors that I often came across, I also developed affection for their idiosyncrasies as they asserted their problems. In Reverberation for example, you have two beautiful people posing for the camera, and the projector is… let’s say coughing, shaking, sneezing, and wheezing. It’s saying not everything is perfect. “C’est la vie!”

There is much to the work, from my perspective at least, that also projects aspects of everyday life, especially in the first two scenes. Andrew and Margaret [Lamarre] are not just two friends posing for the camera, but also stand in for what one might call the “boy and girl” of the movies, the beautiful superstars. However, instead of being “in a movie” and acting out a love story, Andrew and Margaret take us on a tour of the forces that make the cinematic process possible. They sort of hint to the viewer, by their actions, to look around at the film images on screen. At some point perhaps even the three selected locations, may not seem so casual as on first viewing. In addition, thanks perhaps to Andrew and Margaret’s strong presence, the work, though machine-based, also offer indications of the human spirit trapped as well as transcending its machine/chemical character.

Can you talk about your friendship with Andrew Noren? I remember your telling me a story once about the two of you seeing one of Jack Smith’s infamous film screenings on a roof.

We both worked at the Film-Makers’ Coop, we liked each other’s work, and often ended up going to see the same film programs around town. Occasionally I would see Andrew and Margaret socially, either at their place or at a restaurant on the Lower East Side. One of our favorite restaurants was a Polish restaurant across from Tompkins Square where portions were large and the prices quite reasonable.

Through word of mouth we heard Jack was going to do a performance at his loft around midnight. We arrived around 12 a.m. There were about four or five people already there. I believe we were the last to arrive. This was before Jonas saw and wrote about one of Jack’s performances, which then attracted other people to go. Until about 1 a.m. “nothing happened.” Andrew and I thought of leaving when Jack came out and said he did not feel like doing anything on this occasion. He walked out. Then he came back and said “How about a film screening on the roof?” It was a clear night, cold and windy. After spending about half an hour waiting upstairs, Jack came up the stairs carrying some film reels, a projector plus some other stuff. We were freezing, but Jack was dressed lightly. He took a large bedsheet and some weights and jumped from his building to one on the right side and from there to another roof which has a parallel wall to the building we were on. The gap between the buildings was several feet wide and he moved with incredible grace in the semi-darkness. He then placed some weights on the bed sheet and returned to where we were waiting. After connecting extension cords for the projector to cables that went down the stairs to his loft, he set up a turn table, aimed the beam of the projector onto the bed sheet and began to project a reel of film, occasionally changing records. I do not recall what he projected, except that it was mostly black and white footage he might have picked up somewhere on Canal Street that he later used for No President. He also projected some color footage he may have recorded.

It was not what he showed but the spectacle that was memorable. Here we were standing at two or three in the morning, in the middle of the winter, freezing, listening to a sermon and some music from the ’30s while watching footage projected on a waving bedsheet. Our immediate surroundings were dark, but further out you had the skyline of the city and occasionally a police or fire siren. It was quite a spectacle, including us, of course. At some point Jack stopped and said “That’s it for the night.” We helped him take the equipment down and then left. Near the stairs going down, he had left a bowl for donations. There may have been $2 or $3 left for him, that’s all.

Serene Velocity

You were in contact with other New York–based filmmakers as well and have mentioned Michael Snow as being one of your closest friends in New York. I recently saw his *Corpus Callosum, and its visual language, which evokes early trick films, reminded me of your work. Can you elaborate on your friendship and relationship as artists? I remember you telling me that Ken Jacobs and Snow were around and played a part in you recording the sound for Reverberation?

As I mentioned earlier, I was working at the Film-Makers’ Coop, and on one occasion, I heard there was going to be a meeting at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque that had to do with plans to re-open the Cinematheque which was now on Wooster Street. At some point during the meeting (or after the meeting), someone came over to me and introduced himself as Mike Snow. He said his wife, Joyce Wieland, had recently seen one of my films [Wait] at the Yale film festival and liked it quite a bit. At that point all I knew about Mike was that was he was a musician that had played a trumpet in one of Ken Jacobs’s shadow plays performed at a church near Washington Square Park. I got to see Wavelength later on at the Cinematheque when it opened, after it received an award at a Belgium film festival. As with Andrew Noren, Mike and I liked each other’s work. We also shared some similar interests. Music was one. At some point Mike introduced me to Steve Reich, whose music I also much appreciated. When they were in town, Mike and Joyce often invited me for dinner, sometimes as frequently as once a week. It wasn’t just for the company or our mutual film and music interests. They were aware that I had an extremely limited income. On one occasion, Mike and I were walking down the street when he handed me an envelope with $200 and said “Here’s a little grant for you to continue to make films.” On another occasion when he was invited to present Back and Forth at Yale, he insisted they invite me as well and we ended up showing Back and Forth and Reverberation on the same program. It was a great screening, though by the time the screening was over, most of the audience had already left.

Ken Jacobs and Hollis Frampton were also good and generous friends. Regarding Reverberation, as I did not have any 16mm equipment of my own at the time, I asked Ken Jacobs if he could help me re-film the 8mm footage for Reverberation. As I also did not have any sound equipment to work with, I asked Mike Snow if I could use his sound equipment to create the sound track for the film. I created my soundtrack for Reverberation in his living room, while Mike was in his editing room working on Back and Forth. Neither knew what the other was doing until we saw each other’s films at public screenings.

The first festival you mentioned submitting work to was the Yale film festival. Can you talk about what the reaction you heard about from people who were there?

People booing, laughing at the work, throwing things at the screen and by those gestures, not only expressing their own limitations but making it impossible for others to enjoy the work. In spite of such responses, not uncommon in the ’60s and early ’70s, over time, this cinema gathered an audience of individuals genuinely interested and appreciative of this other cinema. It is not a mass audience like that attracted to popular movies… But is that the only criteria for moving image works?

Given the kind of difficulty with making and getting the type of your work you do to be seen, what has compelled you to continue?

I create works because they give me pleasure and satisfaction as well as a sense of inner balance. A work comes into being because of personal necessity. Creating a work for me is like breathing in and breathing out. Or it may be like a sudden gust of wind that then propels me to continue walking and enjoy the breeze. Fortunately, there is a serious and more responsive audience today than I encountered in the late ’60s early ’70s. For example, I recently had three back-to-back screenings in the Bay Area. I did not know what to expect, especially as the screenings were going to take place in the middle of the summer. One venue (The Little Roxie) sold out, the other two (Pacific Film Archive and The Exploratorium) were almost sold out. Projections were excellent and the general response to the works was quite positive and appreciative, at least as far as I could tell during the screenings and the Q&A that followed the screenings. For me, it was a special, memorable, and moving occasion.

History

Being in New York in the late ’60s and throughout the ’70s, what place if any does the city have in your work? Both the physical environment and the cultural environment (cinemas, museums, politics, and community). How have they had an impact on your work?

I like New York, which doesn’t mean I don’t like other places as well, but New York is where I’ve lived most of my life and therefore made more use of it than other places. In the ’60s, ’70s I used to think of it as my ready-made studio and I still do. The sets are all in place and the performers are always in character, made up, and in costume… ready to perform their parts 24/7. But generally depending upon what I’m moved by, I work with the spaces and environments or histories that either inspire or motivate me.

Reverberation, for example, was motivated by my response to the mass destruction of several blocks of buildings in Lower Manhattan, many going back to the early part of the 20th century and some even to the 19th century, all to make way for the World Trade Center. It wasn’t just that good and functioning buildings were being torn down, but in that act, a century of New York City history was being obliterated. Still [1969-71] is another early work prompted by reflections regarding “the city.” It’s very different from Edward Hopper’s paintings Early Sunday Morning and Nighthawks, but in some ways perhaps related, though coming from a different visual and perceptual perspective.

You have mentioned museumgoing was an important activity for you. Can you talk about this experience and any connection it may have to your work?

I love looking at images, be they still or moving. Paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, are all part of that equation, and I much appreciate what New York has to offer in that respect. A good portion of my life involves an interaction with art, and therefore, in addition to artists, I greatly appreciate museums, cinemas, concert halls, as well as books, recordings, etc. It is difficult to imagine a world without them.

You have been compared to Giotto (more than likely because of the Italian painter’s engagement with the very mechanics of representation) and your 1976 film Table has a Cubist-like construction. Painting seems particularly relevant to your work on both an image and conceptual level. What place if any do you see painting having in your work?

In a very general sense I can spend time scanning a painting, moving at my pace and interest from one area of a painting to another. Film, while it is a time-based medium is still a visual phenomenon, and I like to see that option in film as well. So, yes, there is an appreciation of painting in many of the films, however, in addition to what I just mentioned, to the best of my recollection, my approach stems from my childhood experiences of cinema, involvement with early moving image devices, such as flipbooks. Then later on, when I began to work with film, examining the materials and tools I work with and trying to make something worthwhile out of them that was not emulating what other filmmakers had done or were doing.

I work with time, change, and the fact that a moving image is physically always in a state of flux. I am interested in a tactile, sensory, visual exploration of cinematic phenomena—which, again, in a moving image, is always in a state of flux, changing somehow, just as perception is. Still is an interesting work in that respect. Instead of filming an action, each shot denotes a chunk of time, an image of time which accepts moments of activities as being as interesting and relevant as moments when “nothing” happens—like the issue of silence between notes that John Cage bring up in his writings about music. Chance plays a dominant roll in Still as well. The work also offers an affirmation of the two-dimensional plane at the same time it delineates how we read and interpret the photographic image as a three-dimensional space. On a two-dimensional plane, no “object or person” can pass behind or in front of another, yet that is the way we tend to read images. That is a wonderful paradox accentuated in Still.

In addition, each take depicts a different season of the year. Each take also depicts the same space, but the space in each take is optically a bit different. Topically, Still is also making statements regarding the urban environment and the character of the city. If one starts to pay attention to these and other matters in Still, soon enough the work can take on a rich, expressive, vibrant and dynamic force, and decisions may not seem to be as simple and casual as they might on first viewing… But one has to pay attention to and respond afresh to what is being offered from moment to moment for that to come across.

Reverberation

And Still was conceived and created while staring out the window at work? Is it a daydreaming film?

One day while I was working at the Coop, I flushed my desk against a window facing Lexington Avenue so I could look out. The space depicted in Still is more or less the view I had from my desk. Over time I began to reflect upon the stores and activities on the street: Kasto’s Soda-Lunch Restaurant, the early American Furniture Store, the entrance to the apartment building next to it, the lone tree surrounded by concrete, plus the traffic of cars, buses, trucks, and of course people who crossed that space. This was the view of New York I faced eight hours a day. In time, I began to think of it not only as a fragment of New York, but as representing the city itself. I then found a piece of black cardboard in a garbage can near the Coop’s office. For a while I kept it next to my desk, then one day I cut out of it two or three cardboard viewers and placed them on the window facing Lexington Ave. Each rectangle framed a different area of the street in front of me. Over time, I changed the position of these viewers.

It is quite possible that this gesture of mine, of placing viewers on the window, may have been the initial impulse to consider the view I had from my desk of the city, as a possible image for a work on New York City. Reflections on the glass of the window at some point began to suggest the use of a film superimposition as a way to articulate how we read a three-dimensional image on a two dimensional plane, and that was what led to my recording the first four silent takes of Still. Looking at those four camera rolls then led to other considerations, including wanting to create a larger work touching upon observations regarding New York City (and urban space in general), the use of longer takes and the use of sound.

Following from what you mentioned about awareness with regard to Still, consciousness is a major part of your work. Your interest in moving image technologies and early cinema seem to have a Janus-like relationship with consciousness. Can you speak about the relationship consciousness and these very early and basic moving image technologies have? They seem at first glance to be at odds—escapist illusion and active/participatory watching.

My first exposure to cinema took place before I was five years old, walking into a cinema with my mother while a movie on screen was already in progress. The clash between the black-and-white world on screen and the colorful physical auditorium with all these people sitting and watching the ongoing movie was quite surreal. It left a stronger impression than the movie itself did. The next time my mother took me to this same theater (or at least I assume it was the same one), was to see a performance of on-stage magic. A magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat or making someone disappear. It was definitely thrilling. I could sense it was a trick, but “How did they do it”? That was something I wanted to know. That was more interesting and mysterious—the process. A few years later, around the age of eight or ten, I came across a little flipbook. As I activated its pages, the flipbook took on the character of magic.

The magic for me—what endeared me to the flipbook—was an awareness of a cross of various factors: the moving image; my continual awareness that it was composed of a sequential series of still images; that I could bring the moving image to a halt at any time, reverse motion, or flip the pages faster or slower. I was also aware of the blurring of the flipping pages as well as of my hands holding and manipulating the flipbook. The combination of all of these elements was what I found so thrilling and magical. It wasn’t just the figure jumping over a fence that made a moving image experience magical for me… but the combination of all the elements I just described. That was the magic of the moving image for me. And with that memory and perspective is how I began to work with 16mm film some 15 years later.

Table Serene Velocity has always struck me as an attempt to re-create cinema from scratch and an attempt to make yourself, your body, a part of the mechanical process. The film in a sense must pass through you (the focal lengths being adjusted by hand in a torturous night long labor) and is inextricably linked to your physical existence. Can you speak about the history of this film? The story of its making that night? One day I was cleaning a print of Wait and in that process I looked at a little section of the film, paying close attention to the exposure changes from frame to frame, which when projected created a contraction and expansion of space as well as a sense of motion. This simple and basic observation led to a renewed consideration of the intervals between frames—how motion and space is created through the film medium. Let me briefly amplify. From the early days of cinema filmmakers have been involved with the aesthetic of the cut. Breaking up a scene into a series of shots being an early approach. In the 1920s through the work of some filmmakers you have an emphasis on the clash of one image against another on the cut. Later on there is an emphasis on the clash between frames or clusters of frames—meaning, frames of different images clashing. In addition, the slight variations from frame to frame that normally offer an indication of someone walking or the camera moving through space are seen as weak points in the aesthetics of the cut, and is something to be avoided. Great, wonderful work has been created that way. What I saw there however, was the potential of a different cinema, one in which one can bring an emphasis to the plasticity of an image, not just affirming or contradicting the optical realism of a photographic image. Wait was the first work in which I worked along those lines. But at the time, I did not realize that. But then, in late ’69 or early 1970, some vague and very generalized possibilities began to surface. At that point I felt I needed an actual space to work with for a more concrete plan to be realized. I scouted different spaces in the city… but none of them felt right. A few months later, over the summer, I went to Binghamton, New York, to teach a basic six-week filmmaking course. One evening, half way through the course, I was on my way to the Film Department which was located in a basement corridor of the Lecture Hall Building, either to look at some work or pick up some supplies. After going down the stairs to the basement and opening the door to the corridor—Serene Velocity appeared to me in a flash. The corridor in front of me seemed like the perfect setting. A volume of space that seemed plastically pliable. I also loved the glass windows of the doors at the end of the corridor. They led to the outside, which meant during the day daylight would bleed into the corridor. Only after the film was completed did I realize to what degree the “rising Sun” at the end of the film contributed to expanding the space to a sense of infinite space, and that this play between frames could go on forever. Although I did not care for the cream-colored walls, I liked its neutral bare-bones institutional character. Perfect for my needs. It was a space I had walked through many times that summer and never paid much attention to until that moment. I checked other corridors in the Lecture Hall Building, but this was the best one. I then outlined a rough script; determined that the work would be under 30 minutes, and made a test to determine the duration of each bar and the color gel I would use to change the color of the walls. Something I didn’t have to do after finding out that the fluorescent lights rendered the walls, floor, and ceiling of the corridor in a green-blue tone, a color I liked. After my last day of classes that week, possibly a Thursday, I took the bus to New York, purchased fresh film, and then returned to Binghamton. A day or two later, around 7 p.m., I set up the tripod with the camera at one end of the corridor, secured it to the floor with two large buckets of paint, wrapped a piece of masking tape around the zoom lens of the camera, and starting from the middle of the lens, unscientifically re-calibrating the lens, making pen marks every 10 millimeters in each direction until I reached the two ends of the zoom. Then I began to film, recording images single frame. My calculation was that I would be finished recording most of the footage by midnight. I would then rest and take a nap on the pillow I had brought with me. Around 4:30 a.m. I expected to resume recording the rest of the footage, ending around six in the morning. In actuality it was not only painful to record thousands of frames one at a time without a cable release, but it took much longer than I had calculated. I ended working non-stop throughout the night except for a brief break when I ran to the bathroom and let cold water run over my head for a few minutes in order to stay awake. After I finished recording, around 7 a.m., I left the equipment in the film office, and walked very slowly back to the apartment where I was staying. It was a beautiful morning, sunny, with a slight cool breeze, and very quiet, except for the singing birds. When I got to the apartment I flopped on the bed and immediately passed out until late that night. I changed into pajamas and fell asleep again until the next morning. Chris Shields is a New York–based filmmaker and writer. He is a frequent contributor to Art & Antiques magazine and Screen Slate.