Lady Snowblood Many titles in the pantheon of cult cinema have been touted as favorites of exploitation film connoisseur Quentin Tarantino, with varying degrees of veracity. In the case of Toshiya Fujita’s Lady Snowblood swordplay revenge films, I can tell you there’s no doubt about it, and not just because of his well-documented borrowings in Kill Bill Vol. 1. Ten years ago, during a midnight screening at the Sitges Film Festival in Spain, I sat behind Tarantino as he live-narrated the plot of Lady Snowblood (73) to a friend sitting next to him. It was a Japanese-language print with German subtitles, but he spoke with total familiarity and great enthusiasm. (I didn’t even mind the distraction, since I was doing the same thing for a friend sitting next to me.) The influence of the Lady Snowblood films—which recently made their U.S. hi-def debut in a double-feature Blu-ray set from The Criterion Collection, for which I produced a pair of video interviews—go far beyond Tarantino, of course. The archetypal title character has been referenced and repurposed for multiple remakes or re-adaptations of the original comic-book series, as well as more subtle variations which take the core concept of an emotionless woman thirsting for vengeance—itself nothing new at the time the comic was written—and update it for different settings.

Lady Snowblood Originally published in a 51-issue comic book series between February 1972 and March 1973, Lady Snowblood was written by prolific manga author Kazuo Koike, creator of Crying Freeman and Lone Wolf and Cub, and illustrated by Kazuo Kamimura. Reprinted in late 1973 to coincide with the first film’s release, it has remained in print ever since, including an English-language version published by Dark Horse Comics. (The original title, Shurayuki-hime, plays on the Japanese name for Snow White, Shirayuki.) The story follows a young woman named Oyuki, who was born in prison to a mother serving time for murder; the mother dies during the birth and Oyuki is raised outside the prison by a former inmate, and trained in martial arts by a Buddhist priest. It is gradually revealed that her conception and birth was part of her mother’s plan for revenge against four individuals who murdered her husband and raped her. This path of revenge—the title also refers to shurado, one of the six Buddhist realms, specifically a landscape of carnage—is the only reason for Oyuki’s existence. Oyuki is therefore a classical tragic character who forsakes the life of a normal woman in order to exact posthumous justice for her mother and father. The first Lady Snowblood film follows Oyuki as she seeks out and cuts down the villains, the story told in episodic fashion just as Tarantino structured Beatrix Kiddo’s revenge in the Kill Bill series. The sequel, Lady Snowblood 2: Love Song of Vengeance (74), departs from the story of the manga and turns Oyuki into a criminal fugitive. She’s coerced into becoming first a spy, then an assassin, in order to further the ambitions of a group of reactionary government officials (played by a virtual who’s who of Japanese movie villainy) against an anarchist revolutionary (played by future director Juzo Itami).

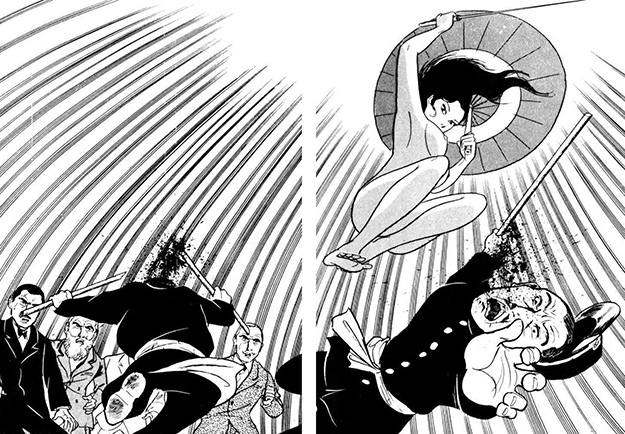

Pages from the Lady Snowblood manga The director of both films, Toshiya Fujita, was a very unlikely choice for the project, which was independently produced by Kikumaru Okuda of Tokyo Films but distributed by major studio Toho (concurrently distributing the Lone Wolf and Cub series). Fujita was born to Japanese parents in 1932 in what would later become North Korea, and began his professional career at Nikkatsu studio in the mid-Fifties, just as their line of internationally flavored “Nikkatsu Action” films were beginning to become popular. First as an assistant director for Toshio Masuda and Koreyoshi Kurahara, and then as a screenwriter, Fujita quickly established himself as a talented part of the Nikkatsu production line, winning an award for adapting Yukio Mishima’s novel Thirst for Love into a hit film for Kurahara in 1967. Fujita began his own career as a director soon after, with entries in the youth-oriented Juvenile Delinquent (64-70) and Stray Cat Rock (70-71) action series, both of which marked his first association with actress Meiko Kaji—his future Oyuki. Fujita soon began to specialize in edgy, realist youth films about aimless young people who were misunderstood by their parents’ generation, quite distinct from the more formulaic Nikkatsu Action product. Wet Sand in August (72) remains his most critically acclaimed work, and even his forays into Nikkatsu’s line of Roman Porno erotic cinema, which the studio launched in 1971, such as Sweet Smell of Eros (73) and Virgin Blues (74), show more artistry and subtlety than similar works in the genre.

Lady Snowblood But the question remains why, apart from the presence of its strong female protagonist, Fujita was specifically chosen by Okuda to helm the first Lady Snowblood film, an independently produced, lavishly constructed action/splatter film based on a comic book. There isn’t really a specific answer, other than to consider the other major players on the film, notably screenwriter Norio Osada, whom we interviewed (along with Koike) for the new Criterion set. Osada himself was stymied by the question, since he was also a surprising choice for the job. His career prior to adapting the comic was focused on yakuza films for directors like Kinji Fukasaku and Yasuo Furuhata, and while Osada and Fujita were good friends personally, they’d never worked together before and had even been employed by competing studios. Osada felt that the answer might lie in the motivations of producer Okuda, whose original inspiration in acquiring the adaptation rights could be found in another manga-to-film series featuring not only a similarly vengeful lead female character, but one played by the very same actress: Meiko Kaji. Kaji, like Fujita, had begun her career at Nikkatsu, but had migrated to rival studio Toei once Nikkatsu made the switch over to Roman Porno production. Having become a star as a result of the success of the Stray Cat Rock series, she was scouted by Toei for the lead role in an oddball new film and potential franchise featuring a classical ninkyo or honorable yakuza character placed in a modern milieu, called Wandering Ginza Butterfly (72). Ostensibly a replacement for major ninkyo actress Junko Fuji, who had recently retired after starring in the long-running Red Peony Gambler (68-72) series, Kaji’s persona and style didn’t suit the classical mold at all, and the series ended after only two entries. But new Toei director Shunya Ito saw something in Kaji, and cast her as the lead in his debut film, an adaptation of a popular but hard-edged comic book series about a female prisoner nicknamed Scorpion—and it was a perfect match. Kaji herself requested that the obscene dialogue of the manga be cut down for the film, so much so that she essays the character almost entirely with her eyes, creating as strong an impression in the role as Clint Eastwood did as the Man With No Name in Sergio Leone’s Italian westerns.

Lady Snowblood 2: Love Song of Vengeance As any fan of Japanese genre cinema knows, Kaji’s Female Convict Scorpion series (72-73) became a major hit both commercially and critically, and was a likely influence on Lady Snowblood, if only in terms of its creation. While writer Toru Shinohara’s Scorpion comic was published two years ahead of Koike’s Snowblood, there is no direct evidence to suggest there was any borrowing or influence, particularly because Koike has often stated that he had long wanted to create a violent revenge story centered on a strong female character, a “demonic woman” in his words, “beautiful outside, but a demon inside . . . a beautiful woman with a beautiful sword who turns cutting people down into an art.” It was also Koike’s choice to set the story in the late-19th-century Meiji era, when Japan was undergoing rapid modernization, often at the expense of traditional values and culture. But even more notably, Koike felt it would improve the story to place Oyuki into a cultural context where women had almost no rights of their own, and where she was an outsider from the moment of her unlikely birth. The Scorpion comics and films, set in contemporary times, convey a very different feeling and it was Okuda’s brilliant choice to marry Kaji’s iconic, nearly wordless, vengeful heroine archetype with Koike’s more lush milieu to create the world of the Lady Snowblood films. One major obstacle for the producer, however, lay in how to convince Kaji to accept the role. By the time production began, the actress had already signaled that she was no longer interested in continuing the Scorpion series and was growing more dissatisfied with violent roles in exploitation films (for instance, she had recently essayed a major dramatic role for Fukasaku in the second of his Battles Without Honor and Humanity films). The answer was Fujita, her former associate from the Nikkatsu days and a filmmaker with whom she’d developed a close rapport; she liked the idea of working with him again, and after reading the Koike manga and seeing its potential for telling a grander tale than the more single mindedly-focused Scorpion series, agreed to star in the film. (It didn’t hurt that she was also contracted to sing the title song, lending more support to her growing music career.)

Lady Snowblood 2: Love Song of Vengeance Okuda’s genius further manifested itself in his choice of Osada as screenwriter, not only because he, like Kaji, already had a close personal friendship with Fujita, but because his style of storytelling was almost completely opposite that of the director. According to Osada, they were like “oil and water,” but could perhaps create something interesting if mixed together. And they certainly did, particularly in the case of the sequel, in which Osada and co-screenwriter Kiyohide Ohara broke free of the strict revenge plot of the manga to explore a thinly veiled political commentary of early-Seventies Japan. (Osada’s work on Fukasaku’s masterful and devastating 1972 war film Under the Flag of the Rising Sun exhibits the same sort of anachronistic commentary.) Fujita, for his part, brings a unique visual artistry and classical composition to the films, particularly the first one, which contrasts sharply with the blood and violence on display, but immediately distinguishes the works as unique not only in the catalog of Toho-distributed chanbara films, but female swordplay films in general. So the style of Fujita’s loosely written, moody youth films combined with the structure of Osada’s tightly scripted and violent yakuza stories, and was placed within the lavish and large-scale setting of Koike’s Meiji-era tale of Buddhist hell and retribution from beyond the grave. When finally embodied on screen by Kaji’s icy expression and steely eyes, always her best asset, no matter the film, the combination was perhaps a “risky adventure,” as Osada put it, but one which resulted in a film like none before it—a bloody splatter movie with loftier, artistic ambitions and an undeniably strong central premise, a unique collaboration which spawned one sequel, countless imitations, and a major inspiration to one of Hollywood’s top directors. Oyuki’s path truly never ends. Marc Walkow is a writer and film programmer living in New York. Formerly a director of the New York Asian Film Festival, he has also produced DVDs and Blu-rays for Criterion and Arrow Video.