A few years ago, at the Morelia International Film Festival in Mexico, I attended a joint master class shared by Bertrand Tavernier and Stephen Frears. The former did most of the talking: where the British director is notoriously a man of few words, Tavernier is, unapologetically, a man of many. But one of the things they both discussed is their tendency to diversify, skipping between entirely different topics from film to film, without obvious continuity and without attempting to impose a consistent auteur identity. Asked why they make so many different types of film, Tavernier said that there were two schools of director. There are miners, who constantly drill deeper and deeper into the same seam, and there are farmers—the English word he used, in fact, was “peasants,” not quite the exact English translation of paysans—who plant different crops at different times and thrive on variety. To which Frears replied, with his trademark mock-grouchiness, “I’ve never been called a peasant before.” “Peasants,” or farmer-directors, generally get a bad press. Critics and film buffs alike usually get most excited about filmmakers who always resemble themselves, or at least who manage to show different aspects of their identity within a reasonably narrow set of parameters. Of course, we all grumble when the Dardennes make another film that seems to adhere too much to their familiar template, or when Wes Anderson paints himself further into his idiosyncratic toy-box corner; and yet much about what we value about these artists is precisely the insistence with which they pursue their Wesness or their Dardennité. By contrast, unless farmer-directors are lucky enough to establish a reputation for being consistently expert, we tend to consider their versatility as a flaw—a character flaw and an artistic one. We mistrust people who speak in too many different voices, or have too many different interests, as if they lacked the strength of character to impose their personality forcefully early on and to keep it imposed, unbendingly, once and for all. But perhaps, as a critic, such mistrust is a habit you learn to resist with time, as you learn how often a single person can change in a lifetime—or even from year to year, from film to film. We’ve all read dismissals (or written them) of filmmakers who are reluctant to display a single unbending self; we call them inconsistent or anonymous. But that quality can also sometimes show selflessness and maturity: an ability to resist the temptation of narcissism. Not every filmmaker is fixated on the imperative “Me” factor associated with the likes of Lars von Trier or Gaspar Noé. Besides, those of us who disparage self-effacing, versatile directors (I know how often I’ve been guilty of this)—haven’t we learned from the original tenets of auteurism, which propose that directors’ deep identities can be hard to discern, hidden as they often are in the diverse fabric of their work? A signature doesn’t always have to be a brand.

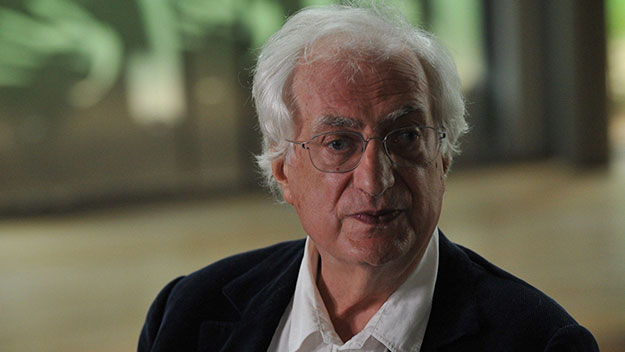

Bertrand Tavernier is one of the more eminent paysans of contemporary film: it’s not easy to detect a consistent sensibility behind films as disparate as, say, The Judge and the Assassin, Coup de Torchon, A Sunday in the Country, Daddy Nostalgia, L. 627, and The Princess of Montpensier, and I haven’t even mentioned his documentaries. But perhaps that sensibility becomes a lot easier to identify in the light of Tavernier’s documentary My Journey Through French Cinema—thanks to which it becomes clear that all his films are made by a man who is obsessive about movies, but also passionately interested in the world and its political realities. It also perhaps emerges that, the more interested an artist is in a whole variety of different things, the less they may need to impose a single stamp on every work they create in response. If you are fascinated, as Tavernier is, by generations of filmmakers as adaptable in their own different ways as Jean Renoir, Jean Becker, Jean-Pierre Melville, and Edmond T. Gréville, then abstaining from writing your own name in screaming upper case may be simply a form of historically minded humility, decency even. It could be argued that Tavernier’s latest film is the most overtly personal of his works, essentially an autobiographical account of his apprenticeship as a cinephile; despite the English release title My Journey…, the French original is more modestly just Voyage à travers le Cinéma Français. The three-hour film is at once a pendant to Tavernier’s and Jean-Pierre Coursodon’s book 50 Ans de Cinéma Américain and the director’s answer to the rather more omnivorous 1995 A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies. My Journey is a curious rag-bag, roughly stitched together: Tavernier mainly speaks to camera, but late in the film appears in conversation with Thierry Frémaux, while along the way throwing in, sometimes abruptly, testimonies from people as diverse as Jean-Paul Gaultier (on his love of Becker’s fashion picture Falbalas) and the late, extravagantly bearded composer Antoine Duhamel (Pierrot le Fou and a number of Tavernier’s own films). There are elements of memoir in My Journey, at times almost Proustian in their free-associativeness—as befits a man who realizes that cinema screens were always somehow connected for him with memories of seeing lights in the sky during the Liberation in his native Lyon. Tavernier remembers that Truffaut’s Shoot the Pianist was the only film he ever heard booed on the Champs Elysées—“along with The Night of the Hunter at the Marbeuf.” He remembers seeing Melville’s Bob le Flambeur several times at Lyon cinema Le Club, where there would be striptease acts between the movies—not because of the stripper, he adds, but nevertheless remembers her somewhat ruefully. Memories become threads: My Journey starts in Lyon, in the park where Tavernier’s parental home once stood, and where he later filmed Philippe Noiret in The Clockmaker of St Paul (74); it was also where his father, during World War II, gave shelter to the great Surrealist writer Louis Aragon, whom Tavernier much later invited to a screening of Godard’s Pierrot le Fou, inspiring a famous article.

Here is Tavernier the childhood cinephile-to-be, not realizing for years that the very first film that excited him, as a 6-year-old child sent to a sanatorium for TB, was Becker’s Dernier Atout (Trump Card, 1942). Here is Tavernier the omnivorous young moviegoer, his own enthusiasms measured against those of the earnest young critics tenderly spoofed by Luc Moullet in his 1989 comedy Les Sièges de l’Alcazar. Here is Tavernier, the political youth, determined to see the banned Octobre à Paris (Jacques Panijel, 1962), about the brutal suppression of the Algerian demonstration of October 1961; and getting his glasses crushed by a CRS officer who had just clubbed him, during the 1968 demonstrations in support of Cinémathèque founder Henri Langlois. Here is Tavernier the apprentice archivist, rescuing prints of Samuel Fuller and Edgar G. Ulmer films—plus two Gréville nitrates—from being turned into combs. Here’s Tavernier the melomane, making us listen to the often underrated brilliance of French film composers, among them Maurice Jaubert, Georges Auric, Jacques Ibert, and Vladimir Kosma, who gave the world—and the jazz repertoire—“Autumn Leaves” and who gets his own section here. My Journey is also a compendium of tributes to some of the filmmakers and movie people that Tavernier loves, some of whom he knew and worked with, either as an assistant director (Melville) or as a publicist (working for producer Georges de Beauregard, after Melville told him he’d never made the grade as an AD). Melville is one of the men Tavernier considers one of his two cinema “godfathers,” along with Claude Sautet (whose fits of rage are mocked, in a delicious clip, by Michel Piccoli). But even when it comes to the godfathers, Tavernier isn’t blinded by admiration: he’s pretty harsh on his Deux Hommes dans Manhattan and Melville’s acting in it, doesn’t rate him as an original writer, and deplores his readiness in berating and humiliating anyone who happened to be in his range (including Jean-Paul Belmondo, and Tavernier himself, who got it in the neck for recommending he see Fritz Lang’s Moonfleet). But he admires Melville in so many other ways—not least for his ingenuity and economic brilliance in managing to make use of every corner of his Studio Jenner as a set, including the back door and the corridor to the bar. Special love and admiration go to the “prince of marginal directors,” Edmond T. Gréville, who had both French and British careers, but who was on the skids by the time Tavernier befriended him in the early ’60s—and wow, does My Journey ever make you want to see Gréville’s “staggeringly bold” film Remous (1934), about sexual impotence, with its delirious series of abrupt cuts during a kissing sequence. Other passions open your eyes to the unknown: the most revelatory clip is of Cet homme est dangereux, directed in 1953 by one Jean Sacha, a nocturnal, super-stylish adventure in which Eddie Constantine, as transatlantic tough guy Lemmy Caution, warns an Anglophone femme, “Speak French. People don’t like subtitles.”

Other names are more canonical. Tavernier proves an astute reader of Becker’s style—his dislike of cheap effect, his rhythm—but also of his character as a filmmaker whose work exuded empathy and decency. He defends Marcel Carné against common criticisms, and argues that his films show him as a solitary man who depended on writer Jacques Prévert to bring him a sense of generosity. Jean Renoir, is of course, the great Jean Renoir—and yet Tavernier looks the facts in the face when it comes to the director’s tendency to be attracted to the winning side, which brought him perilously close to embracing the wrong cause in World War Two. Jean Gabin, who has his own section, said, “As a filmmaker, Renoir was a genius; as a man, he was a whore.” My Journey is a partial, personal sketch of French cinema—some might call it erratic. It’s a rather male one, too: Tavernier tends to focus more on male actors, with asides for Arletty and Simone Signoret, while the only woman director to figure, briefly, is Agnès Varda. It’s just the start of the journey, however. The film ends with a dedication to Becker and Sautet, plus many, many others. But, an end caption tells us, there are many more to come: Autant-Lara, Bresson, Grémillon, Ophüls, Guitry, Tati… All these, you imagine, will complete a composite portrait, through his precursors, of Tavernier the director, the historian, the cinephile. Posterity will decide whether Tavernier the artist is essentially more than the sum of all the films he has watched and thought about. A farmer-director’s humility might lead him to argue that he doesn’t need to be more than that, but what does make him more is the real-world history he has also lived through and documented. The next page of Tavernier’s cinematic map, whenever that’s due, will be well worth exploring. Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.