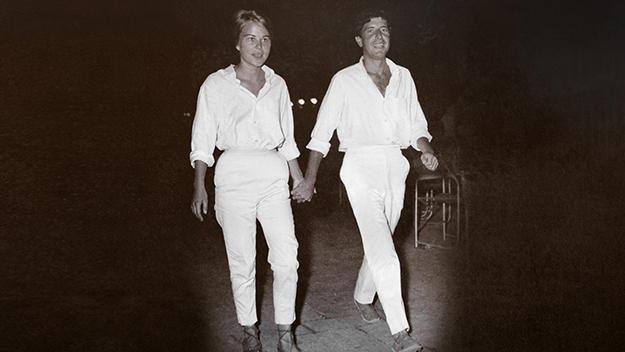

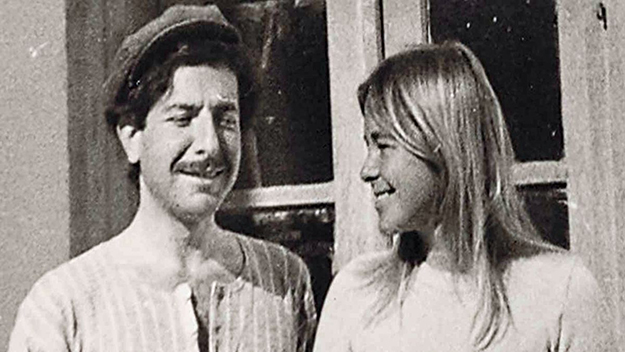

Images from Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love (Nick Broomfield, 2019) One of Leonard Cohen’s most famous songs was originally going to be called “Come On Marianne.” The fact that he changed it to “So Long Marianne” meant that the woman who inspired it, Marianne Ihlen, would not only become famous as his inspiration, but would be forever associated with farewells, with tragic love. The story told in Nick Broomfield’s documentary Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love is about a relationship that isn’t necessarily tragic; indeed, a friend of her says that their last moment of contact, as she listened to a valedictory letter from Cohen on her deathbed, was “a very beautiful end.” Even so, Broomfield’s delicate, elegiac film tells a sad story: perhaps not sad for Ihlen, because after all, who are we to assume that her life with Cohen was defined by sorrow? But this is a story that seems to have been specifically sad for many characters involved, either as central figures or as bystanders, and more generally sad for a generation of bohemians in search of earthly paradise, who encountered disappointments and complications they can’t have imagined at the time. A central theme of the film, beyond the long, complex romance of Marianne and Leonard, is the Greek island community of Hydra, home in the early ’60s to many middle-class expatriates who had left Northern Europe, America, Canada, and elsewhere in search of a life that would be artistically fulfilling and inspiring—or perhaps that just felt like a permanent vacation. Cohen famously arrived there from Montreal in 1960, a struggling poet and novelist, and met Norwegian expatriate Marianne Ihlen, married to novelist Axel Jensen, and mother of a young child, also called Axel. Heard in voiceover, Marianne remembers the first words Leonard ever said to her: “Would you like to join us? We’re sitting outside.” Seeing Leonard in action later in the film, smooth-talking a female admirer, you can imagine this line working only too well, although back then, he didn’t have celebrity as part of his seduction arsenal. What he did have was the fact that Marianne’s marriage was breaking up, and that young Axel needed a father figure around, a role he seems to have filled with cheerful enthusiasm. When Jensen was out of the way, he became Marianne’s partner and she became his muse, to use that fraught term—which Broomfield and a number of interviewees do several times. Even Marianne uses it: “I was his Greek muse, who sat at his feet.” It’s left for us to question what this word really means, and you can’t help concluding, long before the end, that being a muse is a pretty dreadful role to be lumbered with. Cohen wasn’t planning to be a singer; he took to the job after his novel Beautiful Losers—written in baking heat on a Hydra roof, fueled by acid—won terrible reviews and very few readers. Spending half his time in Montreal without Marianne, Leonard met Judy Collins, who covered his song “Suzanne” and encouraged him to sing it with her. After overcoming a debilitating burst of stage fright, Leonard Cohen the internationally famous, notoriously solemn singer-songwriter was born.

His fame was not good for Marianne, not just because it took him away for so much of the time, but because everyone wanted a piece of him, especially women—and especially besotted depressive ones. “I wanted to put him in a cage, lock him up, and swallow the key,” Marianne remembers. “It hurt me so much it always destroyed me.” Leonard can’t have made things easier. He’s heard in voiceover, interviewed late in his life, remembering—in the discreet language of an elegant elder roué—“I was obsessed with gaining women’s favors.” He recalls “this blue movie that I threw myself into,” noting that blue movies are anything but romantic. There’s an extraordinary clip of him, presumably after a concert, engaged in full flirtation with a more than impressed young woman (the man next to her looks very much less than impressed). The scene suggests not a blue movie, but a sophisticated ’70s jet-setting Euro-comedy of manners. There is considerably more footage of Leonard than Marianne in the film, which is inevitable, given the nature of stardom. You can only wonder how it affects a person to be filmed close-up as much as Cohen was at this time: apart from his performances, he’s seen joking, shaving, swimming, generally gadding about. You can’t imagine how this visibility might affect someone whose work appears to be so much about an invisible private life. But you can also imagine how that invisibility affects the life of a person close to him, especially when it’s forced on her; someone mentions that whenever Leonard played a concert, the Norwegian press would want to interview Marianne. But what can a person tell reporters about someone they have loved, or about being their muse? The one grain of insight Marianne gives here about her connection with the songwriting process—and why, after all, should we expect her to give any?—is to say that the song she feels closest to is “Bird on a Wire.” After all, there was an actual wire, and an actual bird on it, and she and Leonard saw it together. Marianne & Leonard offers ample insight into Leonard Cohen’s wild years, not just the women but the drugs. Early on, he’s seen at the Isle of Wight festival in 1970, announcing “So Long Marianne,” and murmuring repeatedly, with a soulful slur, “I hope she’s here… Marianne.” The impression is deeply poignant—but it’s diluted later when Cohen wryly recalls that he was on Mandrax at the time, and “relaxed beyond any reasonable state.” The film also inevitably—given that its director was never known for shyness—contains a certain amount of Nick Broomfield, who was briefly one of Ihlen’s lovers in the ’60s, and as evidence supplies a few photos of himself as a dashing golden youth. He also provides some black and white images of Marianne visiting him in Cardiff, where he was a student; she befriended local children and did the I-Ching daily, and acid frequently.

She embodied the ’60s, in other words, or its utopian, escapist bohemia; she comes across in the film as the residing spirit of Hydra, which at that time was a magnet for lotus eaters, and guzzlers of stronger stuff too. Those who were there, like Broomfield’s friend Richard Vick, remember just how committed people were to the dolce vita, and to pranks like giving acid to donkeys. Hydra was apparently paradise, both in its lifestyle and in its climate and geography, but woe betide those who left and found themselves suffering from serious lotus withdrawal: the story about one happy artistic family, the Johnsons, and what happened after they left the island is harrowing beyond belief. Aviva Layton—who was married to Cohen’s Canadian poet friend Irving Layton, and gives by far the pithiest testimonies—recalls that Hydra was “disastrous for marriages,” and for the children of those marriages. The film is far from judgmental about Marianne’s lifestyle, but it strongly suggests that parents who pursued complex and multifarious romantic lives in the ’60s did so at the risk of their children feeling neglected: the case in point being Marianne’s son Axel, who at one point was sent to experimental British school Summerhill, while his mother returned to her island. He later spent a lot of time in institutions. Both Marianne and Leonard, however, seemed indestructible. One interviewee says that she was the only woman around Cohen who wasn’t starstruck by him: perhaps that was the source of her endurance. She eventually returned to Oslo, married and lived what someone describes as “an ordinary life”; he survived the drugs, the depressions, the cataclysmic embezzlement of $5 million by a manager he regarded as a close friend, and went on to become not only one of the world’s pre-eminent live attractions, but in his august, lugubrious way, a wry, dapper humorist. Marianne is seen shortly before her death at 81, three months before Leonard’s; she’s filmed in hospital by her friend Jan Christian Mollestad, laughing as she enjoys a foot massage. We also see her, in the front row of a Cohen concert in Oslo, smiling and mouthing the words of that particular song; Leonard, in suit and fedora, is seen leaving the stage with some blithe dance steps, a venerable charmer and wiseacre. There are plenty of images of Marianne in the early ’60s, looking as she does in the black and white photo on the back of Cohen’s Songs From a Room. But the image of her that you’re most likely to carry away from this tender film is a recurring piece of footage of her from behind, blonde hair blowing in the wind, obscuring her face: a grainy, slowed-down color shot of her against the blazing intensity of white light on the sea. With or without the discreet guitar accompaniment of Nick Laird-Clowes’s soundtrack, it’s an image that’s as resonant as any song—even a Leonard Cohen one. Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.