Roland Barthes famously said, “Garbo’s face is Idea, [Audrey] Hepburn’s is Event.” The facial showdown between Idea and Event is played out again in Les Hautes Solitudes, Philippe Garrel’s black-and-white silent film of 1974, which receives its first-ever U.S. theatrical run at the Metrograph this week. In it, Idea is incarnated by Jean Seberg, Event by Tina Aumont—in the sense that Seberg is consistently enigmatic, elusive, the embodiment of a semi-absent melancholy, while Aumont incarnates a sexuality that is impish, perverse, irreducibly physical. It’s almost as if the more Aumont brings her bodily energies to the screen, the more Seberg seems to fade before our eyes, dissolving into the bright daylight that she’s often photographed against. It’s hard to know whether Les Hautes Solitudes is best described as an event of a film, or an idea of one. Perhaps it’s fair to say that Garrel’s film is a slender kind of event that simply takes place before our eyes with the minimum of ceremony and leaves viewers to infer from it some kind of unifying idea. The event itself is simple: two actresses appear in front of the camera for 80 minutes, usually separately, very occasionally together, with no sound and no apparent narrative motivation. Two other people appear: the singer Nico, Garrel’s partner at the time, who appears in a brief self-contained prologue (you may recognize one of these images as the portrait seen in color on the sleeve of Nico’s 1974 LP The End); and Laurent Terzieff, who makes the occasional appearance, hair tousled and face brightly lit, in postures recalling those of a 19th-century poetic dandy. Look up Les Hautes Solitudes on IMDb, and you’ll find it classified with the tags “Documentary” and “Biography” and described as “Biographical film about Jean Seberg, loosely based on Nitschz’s [sic] Anti-Christ.” Really, it’s nothing of the kind, although apparently the title, “The High Solitudes,” is indeed inspired by Garrel’s reading of Nietzsche. Strictly speaking, and to be utterly reductive, the film is essentially a series of black and white shots of variable lengths showing Seberg, interspersed with shots of Aumont and very occasionally of Terzieff, plus that Nico prelude, entirely without sound and without any apparent narrative or obvious structuring principle. However, any viewer tempted to impose an imaginary narrative onto the images is not distorting the film’s supposed intentions; after all, Garrel has said, “The idea was to make a film out of the outtakes of a film that never existed in the first place.” You might say that Les Hautes Solitudes contains its own implied phantom narrative, plain to see for anyone whose imagination is inclined to do the work of making it visible.

Garrel shot the film in 1974, a year before the similarly silent Un Ange Passe (An Angel Passes), a portrait of his father, the actor Maurice Garrel. When he made these silent films, Philippe was fascinated with Andy Warhol’s practice of filmed portraiture in the “Screen Tests” or in films such as Couch—a method he regarded, he told filmmaker Gérard Courant, as “a very, very poetic way of making cinema.” He also favored the idea of a highly economical practice, and prided himself on making Les Hautes Solitudes “for the price of a [Citroën] 2CV.” He made the film single-handed: just Garrel operating his camera, alone with his subjects, except occasionally when an assistant was on hand. What he was searching for, he told Courant, was something he had found both in Godard’s Breathless (a film inevitably on his mind while filming that movie’s star, Seberg) and in Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris: that is to say, “qualities of life, much more than qualities of style.” Yet Les Hautes Solitudes has both life—or if you prefer, presence, at its highest intensity—and style. The style comes in the way that Garrel shoots his subjects; I say this at the risk of stating the obvious, because without sound, narrative, or any significant action, all we have is the subjects and the way they are shot. But the film displays at once an extraordinary casualness and a very precise sense of form and composition. Look at the shot, late in the film, of Terzieff leaning forward on a mirrored surface, which he compulsively punches over and over again: two ornate candelabras, both reflected in the mirror, at once frame him and create an anachronistically Gothic effect, bringing a whiff of the artistic garrets of the 1800s. In the early shots of Nico, the painterliness is foregrounded: she’s seen leaning on some kind of slab, a velvet drape hanging behind her. It’s a classical mode of portraiture, in which the human subject is on the verge of being absorbed into a still life. In this sense, the film couldn’t feel less relaxed, less Warholian. But there is palpable spontaneity when Garrel is studying his two lead actresses. For they are actresses, very knowingly performing for the camera; yet they are also documentary subjects, since, in the absence of a readable narrative, Garrel is not just photographing Seberg and Aumont, but making a documentary study of what it is that performers do when they are in front of a camera. We can’t know whether the two women are playing roles, enacting a drama, in any conventional sense, or whether they are just “being themselves”—which is surely a moot point any time that an actor, or indeed any personality, has a camera trained on them (the same goes for Warhol’s people, apparently just “being themselves” but indefatigably selling their irreducible, knowingly louche “star” personas to the viewer).

I haven’t heard or read Garrel talking about how he worked with Aumont, but he has said that he and Seberg “tried to do something in the nature of a psychodrama . . . I was in the position of an observer in relation to her work.” He had only met Seberg the week before filming her, and while making Les Hautes Solitudes, would visit her in her Paris home, talk with her about things other than the film—including her psychoanalysis—and film for one or two hours. She came up with some scenes, apparently just a few minutes before the camera started rolling—things “peculiar to her philosophy,” Garrel has said, and anyone who can lip-read may be able to know what those scenes, and Nico’s earlier dialogue, are actually about. At any rate, it’s clear that Seberg is calling the shots when she’s on screen, and it may well be that Aumont is doing much the same in her sequences. There’s a very clear stereotypical opposition at work between the two women—one dark-haired and Mediterranean-looking, and often seen in dark surroundings, the other blonde, pale-skinned, often shot in harsh daylight that seems at times to absorb her. The counterpointing of the two women makes this something like Garrel’s Persona—or does it only seem that way because of Seberg’s resemblance to Bibi Andersson? Seberg is first seen in bed, in a white nightgown, shifting as if in agony, with her hand to her forehead, as if taking part in some hospital or madhouse drama: it’s hard not to be reminded of the schizophrenic patient she played in Robert Rossen’s Lilith. Later, she’s seen talking in a relaxed fashion, and while she may well not be acting here, her Russian-style patterned top brings its own connotations, so that she seems like a character in a Chekhov play. Seberg’s oddest moment is near the end of the film. She’s seen smiling under a veiled hat with roses, incongruously demure, as if playing someone’s well-mannered bourgeois aunt; she gives a knowing look to the camera, then bursts out laughing as if amused by the ridiculousness of her own actressy demeanor. There are three Seberg moments which particularly qualify as events. One is a super-brief flash of rage suddenly cut in (the film’s only true staccato moment) just before the end. Another is the moment when, standing with her back to us against blazing daylight, Seberg turns, smiles in a haggard way, then suddenly flashes teeth and tongue in a comic grimace, before that expression falls away, leaving her looking utterly weary and washed out. The third moment, earlier on, has her obsessively stuffing pills into her mouth, before Aumont bursts into shot and takes hold of her; allegedly, Seberg swallowed the pills for real.

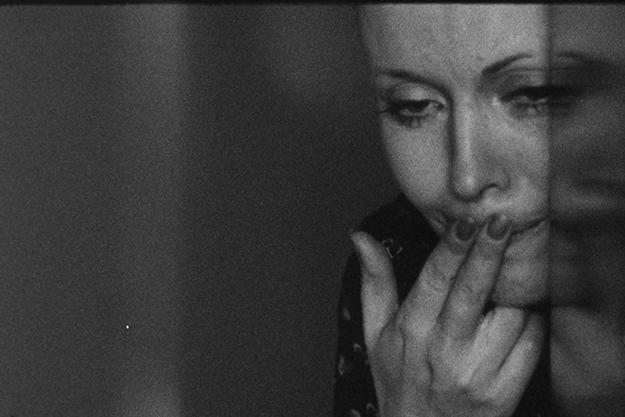

Aumont, meanwhile, exudes the combustive but coolly flirtatious assurance of a young vamp who knows she’s in her prime. For most viewers, Aumont will come to the screen unladen with baggage—the only film I previously remember seeing her in is an obscure 1976 Alexander Whitelaw film, Lifespan, although she also appeared in Fellini’s Casanova. Here she plays the bohemian wild child to the hilt, looking languidly debauched as if she has a thousand crazy nights behind her and who knows how many, or how few, ahead. She’s seen bathing in a head and shoulders close-up; at one point, tenderly brushes Seberg’s hair; but most often is seen gazing quizzically at the camera with dark, heavy-lidded eyes. Her great moment here comes when she looks positively startled as a flick-knife she’s holding suddenly pops into shot; maybe that famous dictum about film only requiring a girl and a gun should be rewritten to cover other kinds of weaponry. Little feels truly casual or accidental in Les Hautes Solitudes, certainly not in the way that it’s shot. Terzieff’s face doubled in a mirror is surely a homage to Jean Marais in Cocteau’s Orphée; while Seberg in a similar pose recalls the sleeping Kiki de Montparnasse in Man Ray’s photograph Black and White. But despite these echoes, what’s most striking about Les Hautes Solitudes is simply the stark evidence of the bodies and the faces in all their living presence, and in the rather bleak context of their history. All four of the actors, or subjects, are dead. Terzieff died in 2010 aged 75, the three women died rather younger: Nico at 49 (in 1988), Aumont aged 60 (in 2006), Seberg at 40 (in 1979), probably having committed suicide, although conspiracy theories continue to circulate. Of the four, it’s Seberg whose screen presence most urgently crackles with resonances of past and future: in Les Hautes Solitudes, we see a faded shadow of the vital gamine archetype she played in Breathless, as well of the more melancholic heroines of Preminger’s Saint Joan and Bonjour Tristesse. In her faintly lined 36-year-old face, we see traces of her Lilith, and we might read the signs of a complex, troubled life: of her ill-treatment by the FBI because of her support for the Black Panthers; of her marriage to novelist and sometime film-maker Romain Gary, whose direction of her in his 1971 thriller Kill! makes oddly trashy use of her sexuality; and presages of her early death in Paris. Such presages, of course, are part of the fiction we unavoidably weave as we watch images of the dead, and it’s in the nature of the images in Les Hautes Solitudes—suggestive of agony or poetic rapture, of sexual passion and excess—that we see this film as a gallery of, or a drama about, the beautiful and damned. In reality, the film is just a set of pictures of three actors and a singer, into which—thanks to the silence surrounding the images—we can read what we wish to. Yet we don’t just read anything, for the title pushes us in a certain direction; these discrete images present us with four people essentially, irreducibly in isolation from each, but gazing at each other across great distances, each one from their own rarefied solitary heights. Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.