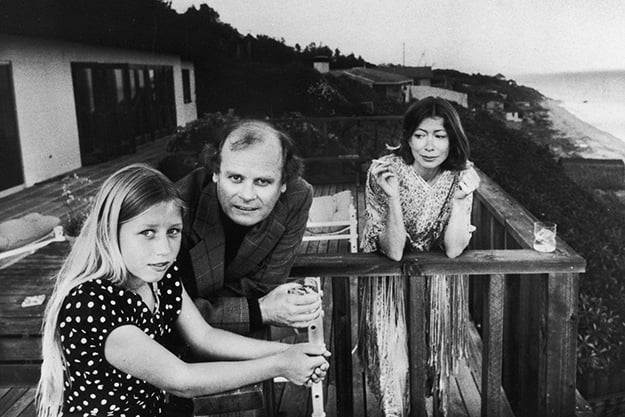

There’s a famous black-and-white photo shown toward the end of Griffin Dunne’s documentary Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold. It’s a family portrait showing Didion, her writer husband John Gregory Dunne, and their adopted daughter Quintana, then a little girl, at their beachfront home in Malibu. John and Quintana stand together on the left, looking at the camera. On the right, further back and leaning on a balcony railing, is Didion, gazing ruefully, somehow apprehensively, at the two of them. Placed at the end of the film, the picture seems to be presented as a portrait of the writer as a crystal gazer: as if Didion, back then, already sees the future in which she would write about the experience of mourning both her husband and daughter, who died very close to each other, Quintana at the age of only 39. But, the film reminds us, we shouldn’t read too much significance into things that may be fortuitous—even if it’s what writers like Didion habitually too, and sometimes rebuke themselves for doing. Didion herself points this out in a passage quoted in the film, recalling a series of coincidences that we might normally tend to think of as uncanny or eerie: she bought the dress for her wedding on the day of the Kennedy assassination; years later Roman Polanski ruined the dress by spilling wine on it; later still, Didion would collect another white dress for Linda Kasabian, key witness in the trial of Charles Manson, who presided over the killing of Polanski’s wife Sharon Tate. “An authentically meaningless chain of correspondences,” Didion wrote—and yet at the time, this chain made sense as much as anything did. You might say that the career of this eminent American fiction writer and pioneer of New Journalism (not a phrase ever used in the film) has been a long, sustained search for meaning, and you might assume that meaning is the necessary center of a writer’s life. The title of Dunne’s documentary quotes W.B. Yeats’s line in “The Second Coming”—the poem that also gave Didion the title of her book Slouching Towards Bethlehem—and yet the film conveys the impression of someone whose clear questioning gaze, directed both at the world and at her own intimate experience, is a center that has held very firmly indeed from article to article, book to book, life event to life event.

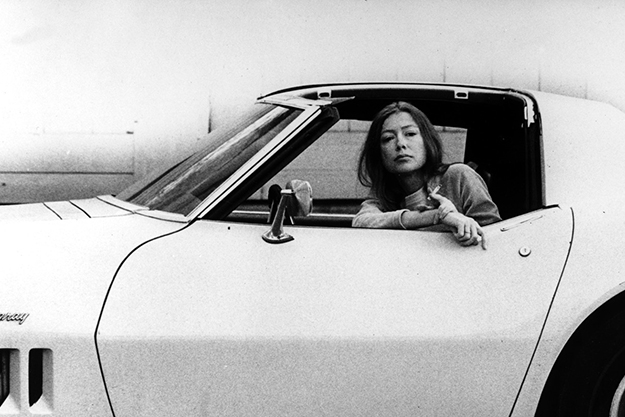

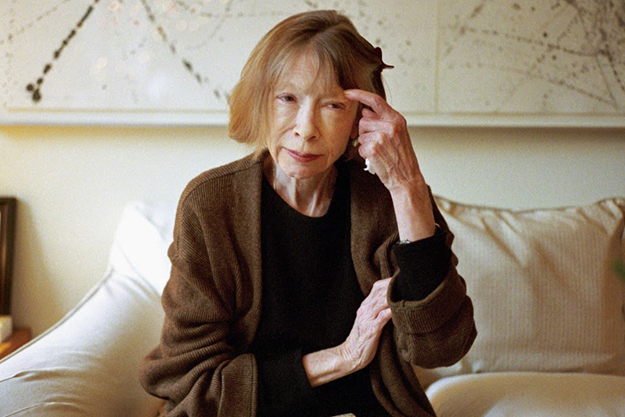

Griffin Dunne—who has regularly directed since the 1990s, although he’s still best known as an actor (After Hours, An American Werewolf in London)—is Didion’s nephew, and therefore has access to a great deal of family material that other documentarists couldn’t have got hold of so easily, including his own childhood memories. He proves the quietly searching interviewer that Didion needs to encourage her to open up on some very private matters—although we learn from her account that as a journalist, she herself was never inclined to ask questions but preferred to sit back and observe people doing what they did. Didion, filmed today at 82, comes across as fragile figure, waving bony arms to give sometimes wry emphasis to otherwise seemingly innocuous points that she makes. She is a mistress, in fact, of the quiet, telling gesture. Interviewed on TV about her book The Year of Magical Thinking, about the grief of losing her husband, she says, “While I was writing it, I was in touch with him in some way.” The interviewer asks, “And when you finished it?” Didion’s hand movement, a high airy wave, semi-dismissive, semi-despairing, says it all: as if the “magic” in the writing process had vaporized in a flash. Didion’s art comes across throughout the film as being somehow essentially agonized: at the very start, we hear her reminiscing about the trauma that the turbulent changes of 1960s American society seemed to induce in her. She was “paralyzed by the conviction that writing was an indecent act . . . that the world as I understood it no longer existed.” She became aware, she says, of “atomization,” faced with “proof that things fall apart”; her work became a matter of coming to terms with disorder. Her investigation of the dark side of the cultural revolution—1968’s Slouching Towards Jerusalem—recorded the horror and the uncertainty beneath the flowered utopia. She recalls walking into a room and seeing a 5-year-old girl on acid. “Let me tell you,” she declares emphatically to Dunne, “it was gold. You live for moments like that, if you’re doing a piece. For good or bad.” You gasp, you almost recoil—then you wonder what the burden of such encounters, and your own knowledge of how you respond to them, does to you over a lifetime. Didion could almost—almost—come across as a monster here, until her later collaborator David Hare steps in to remind us of the moral vision underlying her reportage: as he puts it, her “horror of disorder.” Anyone who likes those Paris Review pieces about the minutiae of writers’ existence will enjoy this film. We learn that Didion used to start the day in dark glasses, always with a cold glass of Coke at hand; she also, when stuck, likes to put a difficult manuscript in the freezer. Literally in the freezer. It’s a very beautiful film, rich in images, from family photos and home-movie moments—for some reason, a big red staircase overlooking a Malibu beach feels the absolutely perfect signifier of Californian domestic utopia—to found material, for which Dunne and editor Ann Collins share a very acute eye (find of the film: a photo of a sad, distracted couple on a dance floor somewhere, sometime). They also have fine radar for Didion’s offhand, telling moments: an interview clip of her looking like a Shelley Duvall at her most fragile, and gently sighing about her novel Play It As It Lays (filmed by Frank Perry in 1972), “I wish it had been made into a better movie.”

There’s not a great deal, however, on her and John’s screenwriting career—nothing on Up Close and Personal or their most improbable collaborative gig, A Star Is Born—but writer Calvin Trillin notes that if the pair had a religious belief, it was in Writers’ Guild medical insurance. Movie people will also be interested to note a contribution by an affable guy who got to know the couple when working as a carpenter on their house, and always enjoyed their parties, even though he felt everyone there was so much smarter than him: Harrison Ford. Much of Dunne’s documentary is about the history of America through Didion’s eyes, from the ’60s/’70s California of which she and John became reigning literary gods and social stars, through to the later period when she began to write political pieces, notably on Dick Cheney, events in El Salvador, and the 1989 assault that became known as the Central Park jogger case, which Didion analyzed for what it revealed about polarized visions of what American society had become. Her thoughts on the political sphere are especially pithy, especially her reading of the hermetic language that politicians use, seemingly for each other’s benefit and to maintain the sealed environment they inhabit but which has little to do with most people’s lived experience: their words, she says, are “signals beyond the pitch of normal hearing.” It’s in this section of the film that Didion also talks about the need to look painful realities in the face: examine something and it’s less scary. As she phrases it, “Keep the snake in your eyeline.” That’s something that she has done particularly since the deaths of her husband and daughter: first, writing about Dunne in her 2005 book The Year of Magical Thinking, then musing on the subsequent death of Quintana for the 2007 play based on that book, a collaboration with David Hare, and then again in 2011’s Blue Nights. Dunne has made a film that in some ways is a nephew’s fond, almost protective tribute but his film also unearths deep reservoirs of pain. Nowhere does Didion keep her personal snake so beadily in her sight as when she says of her daughter (in the film, she alludes to Quintana’s drinking and troubled emotional life), “She’d been given to me to take care of, and I’d failed to do that.” This is a candid, sometimes troubling film; one feels some doors are tactfully left closed, but Didion herself, on camera as in her writing, has preferred to leave others wide ajar. Didion and John Gregory Dunne had been, since the ’60s, the proverbial writerly couple united in life and thought, but she opens up about a stretch of unhappiness in the ’60s and John’s furious temper: a portrait of her from this period (and one always has to be wary of the too-poignant effects of editing) shows her looking anxiously to camera, brow furrowed, hand over her mouth. In a contemporary text, Didion portrays herself as a woman riddled with doubt and skepticism, as she and John went to Hawaii instead of divorcing. It’s a shockingly raw fragment of self-revelation, and Didion’s comment on it is even more revealing. Dunne asks her how John responded when he read the article. Oh, Didion says, he edited it—and adds matter-of-factly, “You used your material.” Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.