“I quickly realized that this was leading nowhere,” says the subject of Corneliu Porumboiu’s Infinite Football, musing on his elaboration of a new set of sports rules. The viewer may sigh in agreement. Throughout the film you keep asking yourself, where is this leading? And why is Poromboiu showing us what we are so patiently watching and trying to make head or tail of? Here’s something of a paradox. Football (i.e., soccer) is—if you’ll excuse me stating the obvious—the goal-oriented pursuit par excellence. Yet there doesn’t seem to be an obvious purpose in Porumboiu’s enjoyably perplexing documentary, nor even in the efforts of his protagonist to reinvent football according to his own set of arcane rules. At various moments, Laurentiu Ginghina—a middle-aged civil servant and former student of ancient Greek—seems determined to reimagine the game for utopian purposes of social transformation. At others, he seems just to want to rewrite football’s rules in order to make the ball itself, rather than the players, the “star” of a match. For much of the time, he more or less acknowledges that he’s getting nowhere with his dreams, yet seems to be chronically, even tragically, addicted to the experience of forever going back to the drawing board. One of the mainstays of the Romanian New Wave, Porumboiu is known for fiction features including Police, Adjective (2009), When Evening Falls on Bucharest or Metabolism (2013), and The Treasure (2015), but this is his second football-themed documentary—the first was The Second Game (2014), which examined a 1988 match in which his father Adrian was referee. His new film moves from actual to merely hypothetical football. It starts with Ginghina—a serious, intense-eyed figure who resembles a permanently baffled John Lithgow—showing Porumboiu the place, now an ice rink, where in the 1980s, he got injured during a football match, fracturing his right fibula after another player kicked his leg. He then takes the director to a now-abandoned metal workshop where a few years later, he received another injury that left him hobbling home in pain on New Year’s Eve, at a pace of two kilometers an hour. The injuries, Ginghina is convinced, changed the course of his life, starting with his disqualification for forestry studies, as the entrance exam involved running. Everything could have turned out differently, he’s convinced—“It was the fault of imposed rules, norms”—and ever since his accidents, Ginghina has committed himself to a symbolic activity of trying to change the world by changing the game of football, not least by making it less violent.

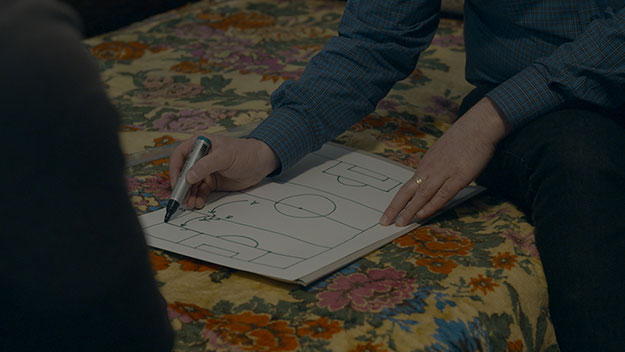

The paradox is that he tries to do so by imposing yet more rules, some of them bizarrely arbitrary-seeming, others logical in a counterintuitive way. Others again will come across as completely inscrutable if, like me, you have zero interest in soccer: in that case, you’ll neither understand nor care about the offside rule, even if you’re aware that Ginghina is hardly unusual in his preoccupation with it. Ginghina’s innovations—which he demonstrates to Porumboiu in flip charts—include cutting off the corners of the field, so as to eliminate spaces that would inevitably get filled by action of the sort that breaks players’ legs. He also has the idea of dividing each team into two sub-teams, each of which can only play in one half of the pitch. This is the fundamental innovation he once attempted to sell to the world, energetically promoting his new system to teams, sports authorities, and other bodies. In 2010, he even traveled to London to meet sports lawyers, but still no one took the bait. On his return, he decided to sub-divide the teams even further. He’s caught in a process of continual revision: not so much infinite football as infinite re-tweaking. All this, once we’re a short way into the film, is already beginning to look like meager material for a documentary. But things take a curious turn when we join Porumboiu in Ginghina’s office for a long sequence that suggests that the course of a film is as hard to predict as that of a match. Ginghina, who seems a highly serious, diligent type, sits at his desk talking about how his job, which he has held for 20 years, is basically boring and how he tried to get away twice, to work in the U.S.; 9/11 scuppered his plans. The drabness of his work actually seems to feed his shy delusions of grandeur: he compares himself to Superman and Spider-Man—faces in the crowd in civilian life, superheroes once they get into costume. It’s the same with him, he says, “filing documents, but in my double life, revolutionizing sport,” and you can’t quite tell if he’s joking at all.

There are banal and distracting interruptions, which appear to be largely what Ginghina’s work consists of: first from a mailman bringing in the office post, then from a cheerful gent escorting an elderly woman who has come to pursue a complaint about a clinic built on her land by the government during the Ceausescu regime. It’s clearly a case that will be in the works for years, and all Ginghina can do, after phoning the appropriate colleague, is to assure her that her papers have now reached Bucharest (“27 years after the Revolution, and to still not have her land back,” comments a shocked Porumboiu). This sequence—which may conceivably be staged, but appears not to be—is reminiscent of the more obviously equivocal Iranian quasi-documentaries, Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up and Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film, in which the action is digressively set off course by the arrival of people who just seem to wander into the frame. Eventually, Ginghina starts to look aggrieved, as if his film’s been taken over by interlopers; it’s a while before he’s able to get back to discussing his life’s dream. That new system of football doesn’t seem to offer any very revolutionary results in practice. We see a test game on an indoor pitch, where not much of interest seems to be happening at all. Despite, or perhaps because of, Ginghina’s principle that decreasing the players’ speed will increase the speed of the ball, there’s palpably little of interest happening on the pitch; it turns out that the players on one half have been standing doing nothing for 20 minutes. Ginghina decides that what’s needed now is a net down the center of the field. “But then,” objects the trainer attending the match, “it won’t be football.”

By this point, it might have struck you that Ginghina’s real interest isn’t in football, but in some sort of practical philosophy of control—and he’s no slacker either when he comes to the more abstract ramifications of his theme, musing aloud on the exact meaning of classical Greek terms such as paideia and metanoia. As emerges in his discussions with Porumboiu, Ginghina wants to redraft the rules of football so that people won’t be injured as he once was—or rather, so that chance, or the workings of social systems beyond our control, are less likely to affect individuals’ fates. But how do you prevent your fate being affected by 9/11, or by the workings of Romanian bureaucracy? You can’t, which is perhaps why Ginghina devotes such obsessive attention to refining his game so that there’s a figure of ideal freedom involved—that is to say, the ball itself. This gets him and Porumboiu into head-spinning arguments. The director is baffled by this idea of the ball’s freedom: surely it’s the players who are the stars of the game? Ginghina objects, “You can be the biggest star but if you don’t have the ball, you’ll just be the star of shampoo commercials.” You can’t help thinking—especially if football itself holds no interest for you—that what’s really at stake here is not so much sport as the nature of cinema itself. One of the questions Porumboiu asks Ginghina is who or what he thinks the fans, or the camera in the case of TV, should be looking at—the ball or the players. This idea of who or what is the appropriate focus, or protagonist, of a match is also a question about who or what is worth looking at, or traditionally considered worth looking at, in cinema. In the drab grey-toned visual field that dominates Porumboiu’s film, as it has dominated so many productions of the Romanian New Wave, there’s little of traditional interest to arrest our attention, and arguably not much of a subject except one middle-aged man’s somewhat dry, pedantic hobbyhorse. And yet all of this, Porumboiu more or less convinces us, is worthy of scrutiny—and possibly, just possibly, resonant as a metaphor for something more complex in terms of the way we look at our lives, and the way we might think of looking at the lives of others. Just when we think the film has become fairly clear in its intentions, Porumboiu gives us more to scratch our heads over. In a strange section near the end, Ginghina’s father holds forth at length about a bizarre blow-up detail from a wedding photo and a truly hideous painting of a woman on a beach, in which the old man detects a play of chaos, order, and “traces.” I’m not sure exactly what’s revealed here, except that Ginghina Sr. is every bit as given to abstruse speculation as his son. A beautiful image—a long, slow drift of the camera along a road in a cold blue landscape—perhaps echoes Ginghina’s painfully protracted hobble home from the workshop in 1987. As for the end credits sequence—animals gambol in silhouette in a luridly kitsch Russian screensaver animation of the ’80s—I have no idea what this is doing here, except perhaps to signal that Infinite Football, from its ostensibly mundane documentary premise, has ended up as the closest that Porumboiu has come to a piece of enigmatic gallery video. As for that field of endeavor, I doubt even Ginghina would be equal to fathoming the ground rules. Infinite Football screens on May 5 as part of Art of the Real at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.