Not the most momentous but, in a comically sour way, perhaps the most painful reminiscence in Laurie Anderson’s film Heart of a Dog comes in a story she tells about being hospitalized after breaking her back as a child. While she was lying immobile in hospital, attendants would read to her from a story about a grey rabbit. Anderson was 12, and immediately before her accident, had been reading A Tale of Two Cities and Crime and Punishment: consequently, she says, “The grey rabbit stories were kind of a slow torture.” I couldn’t help wondering whether this story concealed an allegorical complaint about the fate of an intelligent artist in the music industry: imagine how it must be for someone who has made a mark in visual and performance art of a somewhat abstruse nature to then be defined primarily as a “pop star.” You’d suppose it might feel a little infantilizing. Be that as it may, in Heart of a Dog, Anderson has forged a highly accessible dialogue between her complex, sophisticated concerns—her Crime and Punishment side, if you like—and the childlike, ludic dimension of her persona that has always been a key part of her work, recorded, performed, or otherwise. Heart of a Dog is not Anderson’s first venture into filmmaking—among a handful of directing credits is her own 1986 concert/performance film Home of the Brave—but it has an invention and a candid freshness that make it feel like a debut film by someone that you’d want to hear more from. Anderson is often referred to by admirers as a storyteller above all. Indeed, Heart of a Dog feels like a fireside talk or lantern lecturer by a wise philosopher, one who is no less serious for being occasionally whimsical. The last words spoken are “Is it a pilgrimage? Towards what?” and the film feels as though Anderson is taking her thought processes on a peripatetic ramble with no obvious destination in mind—although there’s a circularity about the work that suggests she has a distinct path in view all along, despite appearances.

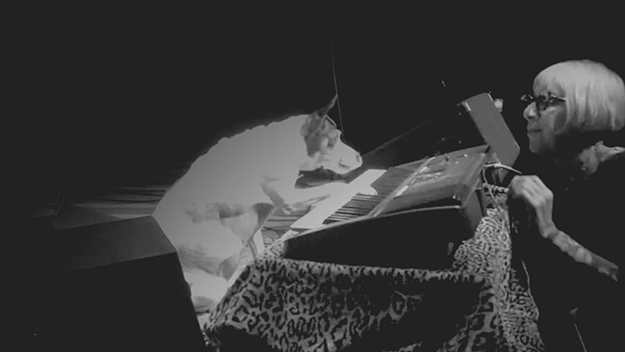

Heart of a Dog gives us Anderson’s first-person voiceover—delivered in that familiar quizzical, fragmented rhythm of hers—and sets it to a diverse assemblage of materials, including her own animation, surveillance imagery, 8mm home movies from her childhood, distorted texts flashed up on screen, and dog’s-eye-view imagery from presumably a GoPro or some such mounted on a pooch’s collar. There are also specific textures that recur, sometimes carrying strong poetic or metaphoric resonances—images seen through water on glass, or projected on crinkled gold leaf echoing the surface of Goya’s painting The Dog. From all this, Anderson spins a sometimes perplexing, but overall captivating discursive and imagistic thread that feels very personal indeed. What she finally unearths, as if in the course of a psychoanalysis, is a certain truth about storytelling itself: extrapolating from a missing detail of a story she has told about herself many times, Anderson concludes that the most important thing in her tale, a harrowing glimpse of the suffering of wounded children, is the very element that she has always suppressed in it. Stories, she concludes, disappear the more we tell them—which brings to mind the insight of Anderson’s sometime collaborator William Burroughs, that we recount our dreams not to remember, but to forget them. Watching and listening to Anderson’s film can lead a critic to free-associate as much as she herself does here, so I’ll try here to be specific about what the film is. Ostensibly, it’s about Anderson’s late pet, a rat terrier named Lolabelle who, late in life—after she started to go blind—acquired some remarkable new skills. Lolabelle’s trainer taught her to paint, to scrape her paws against surfaces so as to leave abstract tracks on a red background, and to sculpt, leaving pawprints in plasticine, which we then see drolly adapted as little clogs, “like the sort Japanese dogs might wear in the rain.” We also see Lolabelle playing keyboards, announcing each chord change with a bark and a change of paw.

All this is comic and cute. But Lolabelle’s status as Anderson’s muse, or alter ego, or wise companion who reveals the true workings of the world to her, becomes most telling in a moment when dog and mistress have fled the frenzy of New York, just after 9/11, for a Californian retreat. They’re walking in the hills when Lolabelle starts looking nervously at the sky, from which hawks suddenly swoop, mistaking her for a rabbit or some other manageable-sized prey. It strikes Anderson that in New York, people have suddenly started doing the same: for the first time, they have sensed the possibility of danger from above. People have abruptly, irreversibly formed a connection with animals’ experience of the world: “It would be that way from now on. We had passed through a door and we’d never be going back.” The associative drift of Anderson’s thought—passing from one subject to another, then another, before perhaps returning to the first—and the way she sometimes overtly forms connections between seemingly unrelated topics, or interprets one topic in terms of another, all of this yields insights in a way that reminded me both of the discursive style of W.G. Sebald and of the incongruous juxtapositions of Robert Lepage. Sometimes Anderson makes her parallels explicit, though that doesn’t make them any less suggestive: commenting on the public safety bomb-awareness ads issued by Homeland Security, Anderson reads the slogan “If You See Something, Say Something” as illustrating Ludwig Wittgenstein’s insight that nothing exists unless it can be brought into being by language. It’s only “saying it” that makes “seeing it” possible. Heart of a Dog worries at its diverse themes like a dog running around streets, sniffing at one find before trotting along to investigate another. Hence, often without any lingering, the film takes in the Iron Mountain data storage facility for corporate documents, Anderson’s speculative daydreaming as a child (“What if the sky froze? What then? Say—are we perhaps made of glass?”), the function of dream and its relation to theories of cot death, and the phenomenon of phosphenes, those patterns of dots and lines that forever flicker over your eyes like “some sort of eternal plotless avant-garde movie—or screensavers… so your brain won’t fall asleep.”

Throughout all this, Heart of a Dog is consistently about memory, love, death, and notions of the afterlife. Anderson is a student of Buddhism, and here invokes the advice of her meditation teacher: “You should learn to feel sad without actually being sad”—she pauses—“which is actually really hard to do.” Listening to the film, there’s an immense charm in the way she weighs words, pausing over them as pondering all this for the first time even as she speaks. It’s a deliberate effect, of course, but it evokes a sense of insights arising spontaneously out of the miasma of unformed thought. It makes her cogitations all the more vivid. There are indeed plenty of things in Heart of a Dog to feel sad about—Anderson’s memory of her mother’s last words, the death of Lolabelle herself, and that of her friend, the artist Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-1978), who died in a way consistent with the Tibetan Book of the Dead. That text, it appears, recommends that we not cry for the dead, because it confuses them; when Matta-Clark died, he had lamas on hand, shouting in his ears, “Gordon—you’re dead!” and issuing instructions for which way to turn in the new space he had entered. That realm, according to the Tibetan Book, is the bardo—not a place, but a process taking 49 days, specifies Anderson, in which the mind dissolves. Anderson also shows us her paintings showing Lolabelle’s own spell in the bardo. It might be a working definition of sentiment, in least in cinema, that we allow ourselves the experience of feeling sad rather than actually being sad—and a cynic might conclude that Heart of a Dog is a sentimental film. But then, a cynic would probably recoil at the idea of a film informed by Buddhist notions of the afterlife, especially made by a dog lover. Some of Anderson’s more nebulous metaphysical commentary I can take or leave, but there’s a lot here that’s very trenchant indeed. First, there’s the film’s philosophical and political speculation—notably the connections that Anderson makes between the surveillance we’re all now routinely subjected to and Kierkegaard’s observation that life is understood backwards but lived forwards. Then there’s the irresistible tenderness and immediacy of the feelings evoked, for the film is itself an act of mourning. The obvious silence in the film hovers around the late Lou Reed, Anderson’s husband; he’s never mentioned until a caption right at the end dedicating the film to him, although he’s listed in the end credits as playing a doctor, and is briefly glimpsed at one point barefoot on a beach, trousers rolled up. The end credits are set to him singing “Turning Time Around” from his 2000 Ecstasy album, and the film’s final still image is of Reed in extreme close-up, snuggling up to Lolabelle. They both look kind of sweetly contented, as if they’ve just enjoyed a good movie.