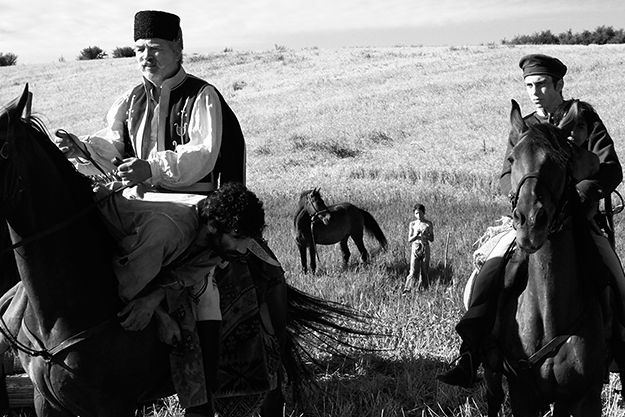

In the Romanian film Aferim!, an elderly traveling lawman, given to philosophizing, asks his son what he thinks people will say about them hundreds of years in the future, then provides his own answer: “Nothing.” It’s hard to argue with him, because the date is 1835, and these characters live in Wallachia—a historical region south of the Carpathians, which eventually became part of Romania. In other words, it’s a time and place that most of us know nothing about. That’s what makes Radu Jude’s film all the more revelatory. The world depicted in Aferim! (which means “Bravo!”) is one that has widely been forgotten, if it was ever much known, and it feels far stranger and most distant than you’d imagine a part of 19th-century Europe to be. It’s as if Jude has opened up a hitherto hidden fold in the map and in the history books—and indeed, in our understanding of contemporary Eastern European cinema, for Aferim! doesn’t resemble much else out there today. Jude, who was AD on Cristi Puiu’s The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, has previously made two features, both present-day stories, The Happiest Girl in the World (09) and Everybody in Our Family (12), of which I’ve only seen the first, a leisurely but caustic drama about a young contest-winner being screwed around with by the media. Aferim! is something entirely different, and a world away from anything that’s yet emerged from the post-Lazarescu Romanian cinema boom. It’s a black-and-white costume drama, a rural manhunt story that takes place mostly with its characters on horseback, or taking breaks at campfires and staging posts—sounds a lot like a Western, doesn’t it? Its main characters are an aging constable, Costandin (Teodor Corban), and his gauche adolescent son Ionita (Mihai Comanoiu). They are on a mission to catch a Gypsy who has run away from the estate where he is a slave, having apparently slept with his nobleman master’s wife. The basic facts of this society are that it’s a feudal culture, ruled over by all-powerful lords, or boyars—yes, as in the long-sleeved caste that you’ll remember from Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible. While the boyars rule over their peasantry, the lowest of the low in this society are the Gypsies, roundly despised by everyone, derisively dubbed “crows” for their dark skin, and officially doomed to slave status. Costandin is seeking the runaway slave at the boyar’s behest; he has authority in the form of a mandate in his pocket, but the term “constable” doesn’t imply that he’s a lawman in the familiar sense. As we see throughout, he treats his status effectively as a way to line his pockets: capturing another fugitive Gypsy, a boy named Tintiric (Alberto Dinache), he sells him to a new master and keeps the money.

Such are the ways of this world, and a very brutal world it is. Despite the date, it is tempting to call this world medieval, and Jude plays up this analogy by giving his dramatic universe a very mediaeval, at least pre-modern look. The priests and peasantry of Aferim! could have stepped out of Andrei Rublev, while a wide shot of a country fair has a distinct echo of Brueghel. Indoors at an inn, the smoky chiaroscuro created by DP Marius Panduru—whose 35mm work is dazzling throughout—could be out of Welles’s Chimes at Midnight (and certainly, Costandin is given to a certain amount of Falstaffian roistering). Overall, this is a world of violence, hatred, and petty contempt—all of which are seen by its inhabitants as everyday matters barely worth getting flustered about. Although there’s little violence on screen (at least, not until the ending), brutality is evident throughout, from Costandin’s opening monologue about the cruel fate of a plague-stricken community to his meeting with the boyar’s wife: he tells her that he could punish her husband for beating her with a cane, but that, since he used his fists, the boyar is perfectly within his rights. Such violence is accepted as the natural way of things: “Adam himself kicked Eve in the stomach,” a servant notes. A fairground Punch and Judy show (or Vasilache and Marioara, as they’re known here) brings the point home. In any case, human life is disposable here: riding past naked corpses by the side of an overturned coach, Ionita notices that one is still breathing. His father, who’s seen so much death that he barely notices it, rides on: “What are we, surgeons?” (the breezy set of English subtitles gets high marks). People’s contempt for other races and communities seems to underpin the basic rules of behavior on which this world runs. There’s a nice comic moment when Costandin converses amiably in Turkish with a visitor, helpfully providing directions to his destination, then reveals that he has deliberately sent his coach the wrong way—and this after the Turk has graciously presented him with gifts. “I hate the Ottomans,” he spits, “filthiest nation on earth” (Wallachia was at this time part of the Ottoman Empire, but under Russian military rule). A traveling priest encountered en route recites a mesmerizing litany of hate, categorizing the races of the world according to arbitrary stereotypes: “Hebrews reads a lot, Greeks talks a lot, Turks has many wives, Arabs has many teeth…”

The racial contempt casually displayed by all these characters makes the hymns of hostility unleashed in The Hateful Eight look like fond banter. The Gypsies are the ultimate targets of this hatred, as we see when the vigilante duo get their man, Carfin (Cuzin Toma, recently seen as the lead in Corneliu Porumboiu’s The Treasure). His treatment is on one level casual, almost affable: Costandin is happy to hear him chat about his sexual adventures and supposed visits to Paris, Leipzig, and Vienna, as they travel along. But Carfin is treated literally as portable goods, bundled on the back of a horse like a parcel, his hands and feet bound, then tied to a post sitting up at night. His wit and astuteness about the world won’t help him: as soon as he’s returned to his boyar, the other slaves set about him, because they’ve all taken beatings on his account—and there’s worse to follow. And the almost larky, picaresque boisterousness of much of the film shouldn’t blind us to the horrifying realities that surely await young Tintiric, left to the mercies of a new master. I said the film feels like a Western—it looks like one too. The opening credits run over a low-angle shot of a cactus-like plant against a vast sky. At different times, the look of the Wallachian landscape, with its plains and mountains, could be Californian, Arizonan, or Mexican. But we shouldn’t rush to assume that any films featuring landscapes, horses, and vigilante justice are “really” Westerns as such—that’s too ready a way of Americanizing whole swaths of world cinema. There’s a European tradition of stories about wandering in vast hostile territories—it goes back to Homer, after all—and Aferim! is very specifically an Eastern European film, even if Jude consciously uses elements of the language of the Western as landscape study. More than anything else, in fact, the look and episodic composition of the film reminded me of Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript, a Polish film based on a Polish writer’s French-language novel set in Spain (that’s no doubt as European as it gets). There’s a strong flavor too of Miklós Jancsó’s grand tableaux in the Sixties, with their sweeping panoramas (but without the armies and the hundreds of horses). The sense of Aferim!’s strangeness comes to head in the final episode, where Costandin and Ionita arrive at the castle of the boyar Iordache, and find his wife lying in an attic compartment up a ladder: this feels like an episode out of Chaucer. The boyar himself is so strange an apparition that he could have walked out of Star Wars, with his huge jar-like headdress, or ishlik, signifying absolute power (it is customary to address a boyar as “bright lord”). He has a falcon on his arm, and a peacock perched on his sofa—pure class—yet a sense of justice that is intensely barbaric. For all his venality and cynicism, Costandin isn’t a cruel man himself—and in the course of the journey, he’s been softened up partly by his son’s gentler outlook, partly by the company of his Gypsy prisoners, partly by an encroaching sense of his own mortality. He pleads lenience for Carfin, to no avail. The final shot is a kind of lyrical shrug: father and son ride off into the landscape (into the sunset, if you must) leaving us aware that nothing has changed in the course of the action, although the world we’ve been watching will not endure long (the Wallachian Revolution would change it decisively 13 years later). Lyrical and nightmarish in turns, but in no way nostalgic, Jude’s reconstruction of this world makes for one of the most striking films of the last year, and a flamboyant anomaly in today’s often cautious world of European art cinema. Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.