Phoenix Perhaps it was the Berlin Schooler’s embrace of melodramatic and noir conceits that turned some people off (many apparently before even seeing it), but Petzold’s borrowings from postwar genre films are key to his latest feature. Phoenix follows a scarred concentration camp survivor as she returns and finds herself inexorably drawn into looking for her husband who thinks her dead. Petzold fixture Nina Hoss plays Nelly, the fragile survivor, while her shifty spouse is called Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld), and the two not-very-German-sounding names suggest an old bar ballad. But when Johnny does not recognize her and makes an unusual job offer, the scenario is closer to a mistaken-identity picture (No Man of Her Own?). While some viewers grumbled about suspension of disbelief, I found the story an uncanny and pointed expression of postwar alienation for survivors, especially those pressed to cope with the past by forgetting it. Nelly faces a double re-assimilation in peacetime Berlin, as a Jew and as a wounded survivor, and around Johnny, she is quite literally asked to impersonate herself, which would make for a permanent state of fractured identity. Petzold’s ruined, mercenary city is a land of rubble and long, deep shadows, and at least one thriving cabaret club, which shares its name with the film; Nelly’s sister meanwhile tries to steer her away from self-destruction, to the point of suggesting a move to an apartment in Haifa, Israel. The deceptively gimmicky plot was written by Petzold and his close collaborator Harun Farocki, who died a little over a month before the film’s world premiere here.

A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence While you might not guess as much from the parodically long title, A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence also has its mind on man’s inhumanity to man and the fact that there’s no escaping the past. Other than being shot on digital (and not for the better), Roy Andersson’s first new feature in seven years does not exactly stake out new ground: its long-take, wide-screen tableaus are populated with his usual dumpy, woebegone figures of fun, most of them made up to look as pale as corpses and walking as elegantly as zombies. The episodes are like elaborations on single-panel newspaper comics: a dying hospital patient clutches her handbag to the frustration of her adult children; a king and his entourage inexplicably appear at a modern-day bar, where his highness takes a shining to a young man. Andersson’s deadpan humor has always cut both ways in his pictures of habit-ridden humans: bovine, potentially harmless, but capable of causing great suffering. Here he restages the devastating truck-gassing scene of his 1991 short World of Glory with a thoroughly off-putting scene of murder for show: British colonial soldiers lead Africans into a giant cask-like contraption that cooks them and channels their moans through trumpets. But in the day-to-day scenes, “I’m happy to hear you’re doing fine” becomes the film’s hopeless refrain, heard whenever someone takes a phone call (even when it’s scientist stepping away from a monkey awaiting open-skull experimentation). Andersson remains fascinated by the violence of history lurking beneath the present, whether explicitly or not, and by the politeness that’s spread like a whitewash over civilization. But his punch-line tendencies have a way of making these ideas feel sentimental; the accumulation of orchestrated scenes dilute his film’s impact this time round. As for his two interminably recurring characters here—a pair of sad-sack traveling salesmen who purvey goofy novelty masks that no one wants—I prefer Dave Foley and Kevin McDonald’s “Nobody likes us” duo from The Kids in the Hall.

While We’re Young Shinya Tsukamoto’s Fires on the Plain splashed fresh gore on the classic Kon Ichikawa adaptation of the Shohei Ooka novel, bringing ample frenetic camerawork and (quite literally) visceral portrayals of the Hell on Earth that was a Philippine island in the waning days of World War II, stalked by abandoned Japanese soldiers going mad. The Tetsuo veteran retains the original’s crowd-pleasing line, “You can eat me!” uttered by a dying soldier to a survivor, which succinctly expresses the gross-out level of the film’s climactic battle scene. But lest Toronto ’14 sound entirely grim and grisly, a little relief came with Noah Baumbach’s entertaining if not profound While We’re Young, which lacked the usual bite present in most of his films. Failed documentarian turned teacher Ben Stiller and his producer wife Naomi Watts are shaken up (and shown up) by an unexpected friendship with cool Williamsburg careerist Adam Driver and his companion Amanda Seyfried. The premise is broad and musty, somewhere between an extended arc on Girls and either a reheated Sixties counterculture comedy or an Eighties hand-wringer for boomers. But Baumbach’s riffs on ambition and creativity and his ambivalence about the younger generation (cf. Greenberg) are diverting. Among the nonfiction work at Toronto, Episode of the Sea employs Dutch fishermen to tell the story of their industry’s survival, straight to the camera, arrayed on boats or in houses. Shot in bracing black-and-white and interspersed with lengthy text scrolls explaining the project, it’s almost like a riposte to the total immersion of Leviathan, taking some inspiration and its title from La Terra Trema (which was originally subtitled “Episode of the Sea” and planned as part of a trilogy). You might also call The Yes-Men Are Revolting self-narrated, as it’s driven by the notorious culture-jammers of the title, as they face divergent paths later in life. But this is an alarmingly weak installment in their continuing adventures, the kind of documentary that feels slapped together to follow a simplistic overarching narrative at the expense of clarity about its complicated subject matter—unwisely, since the Yes-Men’s actions attune us to the shortfalls and shortcuts of media representation.

Tales of the Grim Sleeper My festival visit ended with a definitive high point—or low point—with Tales of the Grim Sleeper. These days Nick Broomfield seems to elicit knowing winces (which is certainly easier to produce than an actual reckoning with his techniques), yet there’s no denying the strength and the horror of his latest work, which delves into a jaw-dropping run of serial murders in South Central Los Angeles. Co-starring his extraordinary, outspoken guide, Pam Brooks, who spent years as a prostitute and addict, the film develops from tabloid investigation into an unexpectedly poignant portrait of life as lived in a routinely harsh yet neighborly stretch of black America and of the cataclysmic effects of racism and violence (from within and without a community). It’s apparently not destined for theaters, but its disturbing truths deserve to be part of the larger cultural conversation.

title: “Festivals Toronto” ShowToc: true date: “2024-05-05” author: “Raymond Matthews”

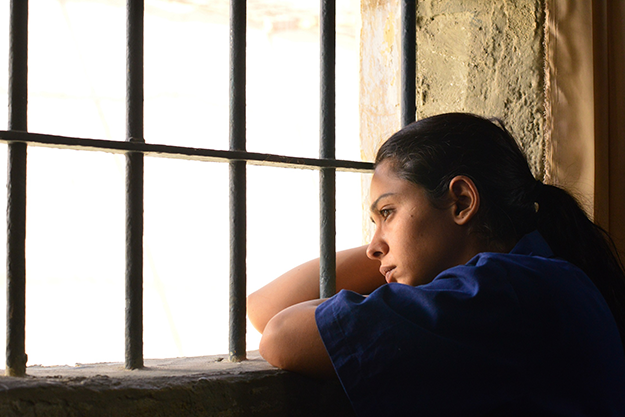

3000 Nights Mai Masri’s drama 3000 Nights begins as Palestinian schoolteacher Layal (Maisa Abd Elhadi) lands in an Israeli jail, accused of abetting a juvenile bomber. Once inside, she withstands cruelty from the female warden, guards, and fellow prisoners, including a pitiless reception by some of her Palestinian cellmates. And that’s all before she realizes she’s pregnant. Years pass—the title denotes Layal’s extravagant sentence, despite flimsy evidence of guilt—during which the authorities use her son Nour as collateral, buying her docility and even her complicity by allowing her to raise him behind bars. But things shift across 3000 Nights, with a winching implacability familiar from modern lockup classics like Hunger (08) or A Prophet (09). Gradually, the jailed Arab women, some male staffers, even some of the Israeli convicts unite in solidarity against a system oppressing them all. As that happens, Layal questions whether individual comforts, including access to her child, should trump other political, moral, and collective obligations that might entail relinquishing Nour. Questioning the sacred natal bond is a huge risk. After all, Lenny Abrahamson’s Room, a very different story about incarcerated motherhood, would likely not have secured the Grolsch People’s Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival without vigorously sanctifying the life-giving codependency of parent and child, after a brief flirtation with critiquing it. Despite or possibly by dint of posing thornier questions, 3000 Nights played three times to packed houses at TIFF, prompted lengthy and effusive Q&A’s with Masri (an acclaimed documentarian making her debut in fiction film), and was acquired mid-festival by the Egyptian-Emirati distributor Mad Solutions. Even better, this level of excitement extended to many other Middle Eastern and North African films in Toronto, whose formal and thematic risk-taking escalates each year, even as their audiences grow visibly larger and more diverse. Credit for this welcome surge of attention goes in part to adventurous scouting and energetic outreach by programmer Rasha Salti, who has curated TIFF’s selections from these regions since 2011. The prime movers, however, are the artists themselves, employing styles and tones all the way from urban realism to brazen experimentation in romances, comedies, action thrillers, documentaries, and historical as well as contemporary dramas. Along the way, at their centers or margins, these films take provocative looks at sex work, torture, trafficking, homophobia, censorship, and multifarious abuses of power. Even three or five years ago, movies from the Middle East and North Africa would likely have broached these topics with less narrative daring and formal brio, if they confronted them at all.

As I Open My Eyes Especially noteworthy at this year’s festival was how many features from this part of the world were directed by women, or at least privileged women’s stories. The Tunisian-French As I Open My Eyes, which won two prizes at Venice during its Toronto run, follows a teenage doctor-in-training named Farah (Baya Medhaffer) who drifts from her studies and prioritizes her role as lead vocalist in an underground rock band. The film takes its name from one of the band’s signature songs, chronicling the inequities they see everywhere in Tunisia, on the eve of the 2010 revolution. Authorities react as well as you might expect. That said, director and co-writer Leyla Bouzid, daughter of envelope-pushing Tunisian auteur Nouri Bouzid, refuses to idealize dissidence. Farah, prone to impetuous narcissism in matters public and private, frequently puts herself and her mates in harm’s way, possibly trusting her class privileges to protect her. Her mother Hayet (Ghalia Benali, a prominent Tunisian singer giving one of the festival’s best performances) discourages Farah’s choices of art over science and rebellion over orthodoxy, but she is no cardboard antagonist. This richly photographed, sonically entrancing drama—a plausible hit with U.S. art-house audiences, if any distributor takes the chance—affords complexity and nuance to every character, without pulling punches about flagrant villainy.

Price of Love Price of Love, directed by rising Ethiopian star Hermon Hailay, does for Addis Ababa what As I Open My Eyes does for Tunis, encapsulating the audiovisual enticements of an eclectic city without exoticism or airbrushing. Young taxi driver Teddy (Eskindir Tameru), haunted by his mother’s death and saved from gambling and drink by a local clergyman, intervenes one night to protect an imperiled prostitute named Fere (Fereweni Gebregergs), whose pimp retaliates by stealing Teddy’s cab. What ensues is both a romance and a rivalry: Teddy strives to help Fere but resents how his altruism keeps putting him at risk, as when his spiritual mentor renounces Teddy at the first sign of backsliding into that same, seamy ecology of hookers and thugs that prematurely claimed his mother. In its way, Price of Love reiterates the paradox of 3000 Nights, advocating camaraderie across lines of difference but admitting the huge personal tolls that new ideals or alliances can extract. Even as melodramatic incidents accumulate, the musical score favors light jazz over broody strings, framing the characters’ stark conundrums within an idiom of improvisation. Teddy and Fere are just two folks trying to get by, making the best choices they can like everyone else in Addis, even as the stakes of joining or separating, staying or leaving, even living or dying continually mount.

Much Loved This tension between individualism and group identity manifested in the program itself, given the attendant gains and losses whenever distinctive concerns and styles of, say, Ethiopian, Palestinian, Lebanese, Tunisian, Algerian, or Moroccan films are folded together as “Middle Eastern and North African.” Even within national traditions, diversity manifested: the jewel-toned colors, bucolic eroticism, and mercurial editing of Hiwot Admasu Getaneh’s short film New Eyes bear little in common with Price of Love’s darker, grainier realism, but each woman’s vision feels essential to whatever “Ethiopian cinema” currently connotes. Meanwhile, the work of Masri, Bouzid, and Hailay furnished useful frames of reference for films like Dégradé (directed by Tarzan and Arab Nasser) and Much Loved (by Nabil Ayouch) that had played at Cannes but deserved more attention, suggesting some linking threads while showcasing, by contrast, unique dimensions of each project. Dégradé, another stimulating debut, traps 13 fractious women in a stifling beauty salon, hiding from outbursts of violence in the streets of Gaza, and subject to each other’s taunts. In the astonishing Much Loved, an intrepid quartet of Moroccan brothel workers increasingly depend on each other’s support as they tangle with judgmental families, closet-case johns, regionalist prejudices, insatiable but penniless obsessives, and other risks endemic to their profession. The fearless script finds the prostitutes chortling at Saudi oil magnates and their hunger for adulation. At least the Saudis tend to have the most cash in their pockets—and are thus ripe for pickpocketing after they’ve exhausted themselves in bed.

The Society It says a lot that Much Loved, so politically thorny, so sexually explicit, so swiftly banned in Morocco, had fierce competition as the bravest film in Toronto, even within this program. In the Iraqi-German short The Society, directed by Osama Rasheed and surely the screen’s first treatment of gay desire in Baghdad, the kind of collective solidarity evinced in so many features is, at best, a far-off dream. Alternating silky and crude black-and-white stocks, interrupting its wisp of a narrative with searing testimonies by actual gay Iraqis, The Society is an eloquently broken-backed object, a series of shards on its way to being a film—exactly as its subject requires.

Starve Your Dog Finally, none of these films prepare you for the formal and rhetorical audacity of Hicham Lasri’s Starve Your Dog, a cherry-bomb of political anger rendered in hard digital images and gangrenous colors. Commencing with a direct-to-camera tirade about present conditions in Morocco, voiced by an elderly woman who expects to be killed for speaking up, the movie builds slowly to its narrative crux: an interview between a journalist named Rita (Latefa Ahrrare) and the aging Driss Basri (Jirari Ben Aissa), an infamous executor of state-sanctioned violence against Moroccan citizens for almost 20 years. Imagine Death and the Maiden rebuilt as “gotcha” journalism, or Katie Couric settling in to grill Robert Mugabe but as a cultural insider with her own wounds to nurse. The content and tone of Starve Your Dog—which cross-cuts several times to Basri’s deranged and homeless daughter, exposing herself to strangers on the street for a few coins—are so livid that the camera itself enters a crisis state. With canted angles abounding, and several images beveled into hall-of-mirrors reflections of themselves, Starve Your Dog feels jagged and hot to the touch. It’s the second film in a planned trilogy by Lasri; the mind reels as to where he might proceed from this discomfiting but urgent spectacle. When he completes that third film, I place my bets on Salti to exhibit it. As we collectively open our eyes to more Middle Eastern cinema, Toronto keeps emerging as an essential place to look.