The Merchant of Venice The history of film is a history of loss, of studio archives dumped into the Pacific and nitrate prints melted down for silver. That is why the Museum of Modern Art’s festival of film preservation, To Save and Project, feels like a yearly miracle. Now in its 13th edition, it celebrates the work of film archives the world over, and though the fest has slimmed down from previous years, it still offers a cornucopia of heretofore unknown pleasures that range from silent German monster movies and Clara Bow comedies all the way to experimental documentaries and Canadian pulp pastiches. The starring archive is the Munich Filmmuseum, which is presenting a program of rare Orson Welles films, including a work print of the unreleased ocean thriller The Deep (67), a reconstruction of his shot-for-TV The Merchant of Venice (69), and an extended version of Norman Foster’s Journey Into Fear (43), which Welles supervised. The most unusual item presented by the Munich Filmmuseum however, is Otto Rippert’s Homunculus (1916) a six-episode German science-fiction serial about a test-tube baby who grows into a world-destroying monster. Only one episode was thought to have survived, but the Filmmuseum’s Stefan Droessler has painstakingly restored it to an approximation of its original length. Originally released in 1916 while World War I still raged, it was cut down into three parts and re-released in 1920. The original structure and inter-titles from the original version were lost, and had to be reconstructed from publicity and other materials from the 1920 release. The end result is seamless and utterly gripping, as if Frankenstein’s monster had become enraptured by German Romantic poetry.

Homunculus The Homunculus (Olaf Fønss) looks like a hastily assembled Dracula costume, with black cape and charcoal applied under the eyes. He is possessed of super strength, but in the early chapters is on a search for how to love and be loved, a melancholic vagabond who pours out his sadness into a diary. He is a Heinrich Heine who could rip a door off its hinges. He channels the rage from his romantic failures into super-villainy, eventually setting the whole world on fire. The emphasis on scientific experimentation on humans, a proto-eugenics, lends the film a troubling foreshadowing of National Socialism, as the only way to destroy the Homunculus is to create another lab-created superman and point them against each other, a policy of mutually assured destruction that ends the film on a literal cliffhanger. The other silent-era standout in the series is Get Your Man (28), a sprightly Paramount comedy directed by Dorothy Arzner. It’s that same old story about a young betrothed Frenchman who falls in love with an American flapper after getting locked inside a wax museum. That flapper is Clara Bow, and she offers a feast of flirtatious enticements, most notably a heaping helping of side-eye. Two reels are missing, mostly from the wax museum sequence, and the Library of Congress has filled these in with production stills and intertitles. Dorothy Arzner was one of only a few female directors during the early studio era, and the first woman to become a member of the DGA (in 1938). The late, great Chantal Akerman was another trailblazer, but in the mostly male European art film scene. The Cinémathèque Royale presents restorations of her masterpiece of domestic housewife terror Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (75), to be introduced by its cinematographer Babette Mangolte, as well as her early short Saute ma ville (68) and the 1976 feature Je tu il elle, in which Akerman’s solitary apartment dweller uses sex as a salve and an escape.

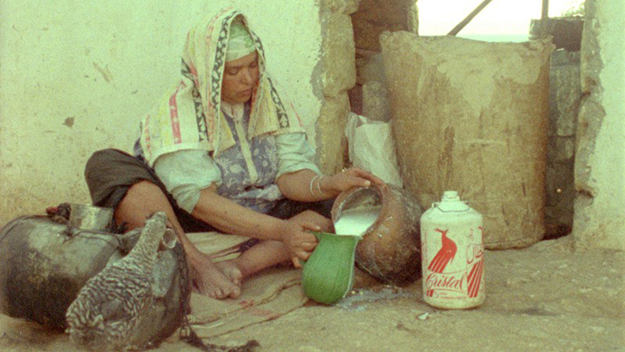

Alyam Alyam (Oh the Days) Throughout her career Akerman shot intensely personal material from an observational distance, trying to make the intimate epic, as she accomplished in News From Home (77) and her final feature No Home Movie, capturing her ailing mother’s final days. As the boundaries of what makes a “documentary” film shifts and expands, Akerman’s influence continues to reverberate. It can be seen in To Save and Project in Alyam Alyam (Oh the Days), a quiet, meditative 1978 portrait of an economically depressed region in Casablanca written and directed by Ahmed el Maanouni (Transes). It depicts work and those seeking work, with bracing scenes of camel slaughter to portraits of kids who want to move to France to send money home. Europe is the structuring absence here, a destination and solution, but it is also what is emptying the town of its youth. Sad and beautiful, it was shot in 16mm and restored by the Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory. Director Abderrahmane Sissako (Timbuktu) will introduce the screening. In Les Ordres (Orderers, 1974), director Michel Brault opts for documentary reconstruction to illustrate the October Crisis of 1970 in Quebec. After a cabinet minister and British diplomat were kidnapped by the secessionist Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act to impose virtual martial law on the province. They proceeded to arrest and detain 497 people without needing to secure warrants or even press charges. Brault hired nonprofessional actors from the same backgrounds as those arrested, and used cinema verité techniques (handheld cameras, direct sound) to channel the atmosphere and textures of the period. Taking text straight from detainee interviews, it focuses on the everyday details: who will watch the kids, the consistency of prison porridge, the maddening color of the jailhouse walls. Brault won the Best Director prize at Cannes, and the restoration by Éléphant, mémoire du cinéma Québécois, brings out every gritty grain of this quietly defiant film.

Crime Wave If you are looking for more colorful Canadian fare, take in John Paizs’ Crime Wave (85), a delirious candy-colored parody of American pulps recently restored by the Toronto International Film Festival. This scrappy independent production is a nesting doll of crime narratives. The framing device depicts a strong, silent, aspiring scribe, Steven Penny (Paizs), who can write beginnings and endings to crime stories but never the middles. With the encouragement of his landlord’s daughter, he keeps cranking them out, and the movie is made up of these absurdist sketches, of murderous Amway-type salesman, Elvis impersonator wackos, and cowboy sex maniacs, with none of that boring exposition to gunk it up. With its endless divergent stories and polymorphous perversity, it’s no surprise that this Winnipeg-shot film was a major influence on Guy Maddin. Paizs, who later went on to work on The Kids in the Hall, will be in town to introduce. With over 70 features and shorts from 16 countries, To Save and Project is a virtual tour of the world’s premiere film archives. As the keepers of the culture for this most fragile of arts, archivists are the anonymous heroes of the film industry. This event justifiably makes them the star, where the Munich Filmmuseum, Library of Congress, Cineteca di Bologna, and so many more take center stage. Films wouldn’t have a history without them.