Harmonium “A little too cold to go swimming” proved to be the perfect temperature for filmgoing at this year’s Miami Film Festival, held March 3 to 12. Organized by the Miami Film Society and Miami-Dade College, the 34th edition offered a diverse selection of films from around the world, which, taken with the festival’s schedule (only evening screenings on weekdays), testifies to its commitment to engaging with the area’s culturally vibrant community. The 10-day regional festival, which took place across six theaters (and a few party venues) in Miami Beach, offers internationally flavored picks, with a special focus on Spanish and Latin American film. And given Miami’s cosmopolitan flavor and geographical location, the difference between regional and international isn’t always so distant. This isn’t to say that this highly accessible festival in any way pandered to audiences. Along with films like Kôji Fukada’s mordant tragedy Harmonium (which bagged the critics’ prize, selected by a jury of which I was a part), even the crowd-pleasers, such as Nnegest Likké’s culture-clash romance Everything But a Man and Dudley Alexis’s Haitian culinary documentary Liberty in a Soup, didn’t shy away from issues of race and class, or fraught political history. Considering the state of the world, to what extent can such conflicts continue to be ignored (in the country often directly or indirectly involved in them) or used as backdrops for white Hollywood stars? Two standouts that center their narratives on historical trauma were El Amparo, which tells the true story of a 1988 incident where the Venezuelan army killed 12 fisherman they claimed were terrorists, and The Dark Wind, which fictionalizes the 2014 Yazidi genocide of Kurds by ISIS and its aftermath.

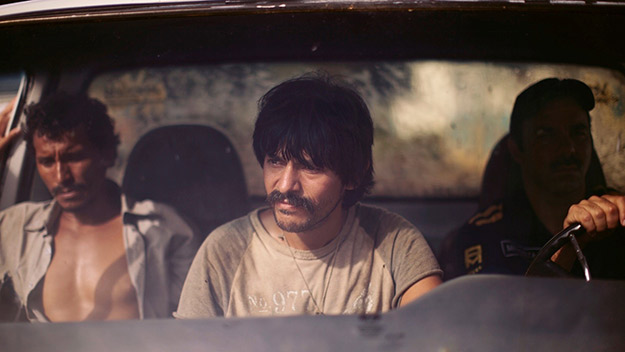

El Amparo Bolstered by superb performances, the majority of El Amparo follows the two survivors of the massacre, Chumba and Pinilla, as they struggle to understand what really happened, whose legal advice to follow, and how to protect their families. The film leaves open the possibility that the men were unwittingly called along on some mission, suggested by a shady local (the same mysterious guy who told the man who organized the fishing trip where to go on the river) who keeps telling them to plead guilty and ask questions later—but, then, so do several representatives of the army. Director Roberto Calzadilla conveys the laze-inducing heat of the setting through beautiful but never overly aestheticized photography, nor does he overplay emotional moments: when Chumba and Pinilla are interviewed by a reporter on live television and finally break down while talking about their dead companions, it’s a punch in the gut. Hussein Hassan’s The Dark Wind, with its grittier digital look and occasionally stilted acting, feels far less polished by comparison, but is nevertheless a remarkable document. Shot in Hassan’s native Iraq, the narrative is a frank treatment of life there for Kurds: Reko (Rekesh Shahbaz) and Pero (Diman Zandi) are engaged to be wed, but after Pero is captured and sexually abused by ISIS, a return to what passed for normal proves to be impossible. Through a combination of chance, persistence, and the help of an all-female regiment of Peshmerga fighters, the couple is reunited, but Pero’s experience leaves her in a hair-trigger state vacillating between catatonia and hysteria. Even though Reko accepts her and still wants to marry, the elders (and his own father) consider her to be “impure”; meanwhile, her family, while supportive, don’t really know how to help her recover from such trauma, and at a crucial juncture make things significantly worse for Pero. The ending leaves open the possibility of hope for the couple, but it’s colored by everything that’s come before—it takes more than best intentions to fix certain injustices.

Are We Not Cats A vastly different—and far less substantive—treatment of coupling through hardship was Xander Robin’s Are We Not Cats. Like the tougher, grosser American cousin of Carax’s Lovers on the Bridge, the film centers its drama upon the indignities of being a poor young person outside of a trendy metropolis. After being rejected by his girlfriend, fired from his job as a garbage man, and kicked out of his elderly Russian parents’ apartment, Eliezer (Michael Patrick Nicholson) agrees to deliver a car motor to an upstate New York body shop for some much-needed cash. He decides to stick around after laying eyes on Anya (Chelsea Lopez), a manic pixie dreamgirl with an industrial goth streak and a bottomless appetite for eating hair—who happens to be dating the motor’s recipient, an antifreeze-swilling guy who’s at least as pathetic as Eliezer. The amount of follicle consumption, coupled with the bullying coercion that men can unleash on women who are already spoken for, gives the proceedings a grotesqueness that’s rare outside of horror. Yet for all this unsparing bleakness, the film’s utterly unimaginative final act is a total copout. Not everything I sampled in Miami bore a pallor of desperation: the undeniable high point of the opening weekend was a talk with Almodóvar muse Rossy de Palma. Held at the exquisite Olympia Theater—hands-down the most impressive movie palace I’ve ever been in, complete with pre-show organist—the event began with the video component of Jessica Mitrani’s Travelling Lady, a multimedia installation/performance work that features de Palma as the eponymous traveling lady, a perpetually transforming character inspired by Nellie Bly who both challenges and falls prey to society’s expectations of female behavior. Afterwards, the audience was treated to de Palma performing excerpts from her one-woman show at Milan’s famous Piccolo Teatro, which incorporated elements of Aragon-inspired surrealism and flamenco. Needless to say, it was a fantastic sight to behold. Although the ensuing Q&A didn’t elicit the most high-caliber audience responses (one fan just complimented her legs), it was extremely entertaining to watch de Palma impart wisdom to her adoring public. The event was also the perfect compliment to a talk by actor Sarah Gadon earlier in the day, which focused on the ways in which she had employed her knowledge of film and feminism to complicate or expand her roles—a reminder that there are many types of authorship. As Miami’s cinephile culture continues to expand—there are four art-house theaters (five if you count the one in Ft. Lauderdale)—MFF proves to be a welcoming place for film lovers to discover and rediscover both movies and their many makers. The only obstacle to enjoyment, as any Miami native could tell you, is the traffic.