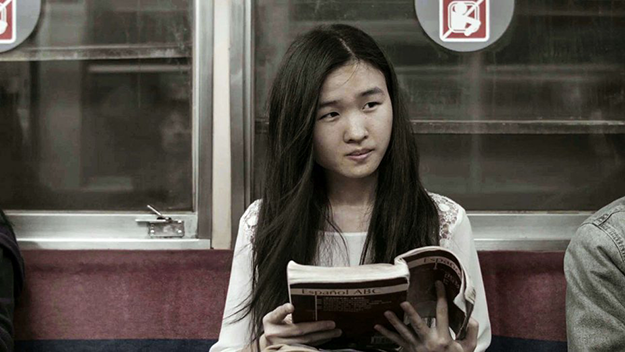

The Future Perfect My last visit to Locarno, I think, was back in 1992, and I don’t remember too much except for baking, humid nights dozing off during open-air screenings in the vast, stately Piazza Grande. So for all intents and purposes, this was my first visit. Getting the hang of an unfamiliar festival can be difficult, but my ride was made easier by the fact that I was doing jury service for the Swatch First Feature Award: build your viewing around a strict timetable of 20 films, and everything else slots into place easily. Jury protocol entails some discretion about what I saw, but I can honestly say that, between the three feature juries doing duty this year—the others being Arturo Ripstein’s international competition jury and the “Cineasti del Presente” jury under Dario Argento—most of the films that I valued, in whatever section, were honored one way or another. My jury’s First Feature award went to The Future Perfect, an Argentinian film by German director Nele Wohlatz. On the surface, it’s a detached, somewhat formal comedy built around a slender premise: a young Chinese woman joins her parents in Buenos Aires and struggles to learn Spanish. At first, her linguistic limitations leave her flailing to understand the new world around her, but as she comes to achieve fluency, her prospects—and her emotional and imaginative universe—expand accordingly. Sharply self-reflexive, with a serious underlay of philosophical inquiry, the film features a deliciously downbeat performance from Zhang Xiaobin. It’s simply a delight to find a film that’s so insightful about issues of identity, exile, language and self—and at the same time, so elegantly funny.

Still Life Another of our awards was to Gorge Coeur Ventre by French director Maud Alpi. The official English-language title is Still Life, but the more evocative original means Throat Heart Belly. This impressionistic but savage piece is set almost entirely within a slaughterhouse, the action seen largely through the eyes of a dog, the companion of a young abattoir worker. The territory is somewhat familiar, although it’s salutary to revisit it—the world of Franju’s Blood of the Beasts, a world that humanity is no closer to abandoning. Still Life is as much about an architectural nightmare—the inner mazes of the death factory—as it is about animal rights per se, and it’s photographed with unnerving beauty, if that’s the word, by Jonathan Ricquebourg, a name to watch (he also shot Albert Serra’s recent The Death of Louis XIV). Ending with a haunting utopian vision of a post-human republic of dogs, this was one of the steeliest statements here. Alpi’s film was the strongest of a mixed French selection. Axelle Ropert’s The Apple of My Eye was a one-joke romcom about a musician who pretends to be blind to court a blind woman. The crowd-pleasing Swiss co-production Moka, by Frédéric Mermoud, was a solid, downbeat psychological thriller in Chabrol mode, distinguished mainly by a flawless lead from Emmanuelle Devos. One to keep an eye on, though, is first-timer Julien Samani, whose The Young One—adapted from Joseph Conrad’s Youth—made the most of budget restrictions that gave this sea-going chamber drama the taut clarity of a parable. This year’s Golden Leopard winner was Godless, by Bulgarian first-timer Ralitza Petrova. Set in a small town, it’s the harsh realist story of a young woman working as a carer to the elderly, with a sideline selling their identity cards to a gang that uses them for money laundering—with local cops and judges all in on the scam. Petrova depicts a totally corrupt post-Communist world in which hope, justice, and compassion seem absent—yet keeps a tiny flame of possible redemption alight for her antiheroine, one of whose patients conducts a religious choir. Transcending expectations of Eastern European miserabilism—although I know some viewers felt it came close—Petrova’s film is distinguished by a distinct edge of Jim Thompson-esque blackness in its crime narrative, while Irena Ivanova’s taciturn performance, which won a deserved Best Actress prize, draws out the story’s nuances in unexpected colors.

Scarred Hearts With last year’s historical epic Aferim!, Radu Jude redrew the map of possibilities for contemporary Romanian cinema, and Scarred Hearts—which won the Special Jury Prize—is the most interesting production I’ve seen from his country this year, notwithstanding the recent Cannes crop. Set at a Black Sea sanatorium in 1937, and based on an autobiographical novel by Max Blecher, it’s about a young man with bone tuberculosis who winds up immobilised with his torso in plaster. This doesn’t stop him having a riotous time in his enclosed new environment, where patients contrive to make love, have boozy parties and revel in poetry, politics, and the turbulence of the times. Despite its bleak theme, the film brims with anarchic life, and contains the festival’s funniest sex scene, as two plaster-enclosed patients’ attempt at coitus ends with our hero wheeled off screaming in agony. “Do drop by again!” calls out his inamorata. Marius Panduru’s Academy-ratio photography, each scene staged in mainly fixed tableaux, makes the film as memorable formally as it is dramatically. I’d been hearing for years that Locarno is the place to go if you have a taste for the outré, and I wasn’t disappointed. There were two terrifically enjoyable Japanese films. Destruction Babies was, if you like, Tetsuya Mariko’s answer to Fight Club or Harmony Korine’s abandoned punch-up project Fight Harm. It’s about a man who goes round obsessively picking fights with strangers: his masochistic violence attracts a deranged acolyte while spreading epidemically. There’s an apparent program of state-of-the-nation diagnosis here, but any clear message is unsettlingly eclipsed by the pleasure you get from the film’s out-and-out macho perversity. Even a Jason Statham fistfest movie wouldn’t get you thinking “Oof! Dat’s gotta hurt!” nearly as much. More benign was Wet Woman in the Wind, Ahihiko Shiota’s contribution to Nikkatsu’s relaunched “Roman Porno” series. Concise at 77 minutes, and hyper-economical—a week to write, a week to shoot—it features Yuki Mamiya as a walking isotope of female libido, who latches onto a reclusive playwright and brings the house down with her frenetic activity. Literally brings the house down—in one scene, she causes the hero’s lean-to shack to crash to the ground, cuts herself a hole to wriggle through, then carries on blithely thrashing. There surely hasn’t been a sex film this euphorically jolly since the prime of Russ Meyer. In a league of its own when it came to strangeness was The Ornithologist, the latest from João Pedro Rodrigues—a gay quasi-religious pilgrimage story, in which a birdwatcher (French art-house muscle boy Paul Hamy) plays a modern version of St Anthony, with a little St. Sebastian thrown in. As he undergoes various trials—he’s tied up by two Chinese women, encounters a cabal of folk demons, then has a violent/erotic encounter with a young shepherd named Jesus—the film maps an eccentric, lyrical, unpredictable landscape entirely its own. Even so, I couldn’t help thinking that this is how it would look if Alain Guiraudie and David Lynch got together to remake Buñuel’s The Milky Way.

The Challenge More strange bird-related visions came in Italian filmmaker/artist Yuri Ancarani’s The Challenge, in which fabulously wealthy men converge in the Qatari desert, alongside local bike gangs and monster truck racers, for a falconry showdown. The imagery in this showdown is so surreal—a leopard in the passenger seat of a car, choppers with gold handlebars—and the film is so elegantly shot, with heightened attention to staging and symmetry, that at first thought I was watching a gallery-art fabulation à la Matthew Barney. But no, The Challenge apparently records a real tournament, and marks a fascinating convergence between ethnography, style-magazine reportage and art-video surrealism. It’s also shot by Jonathan Riquebourg, this time in opulent shades of desert gold. It was a vintage year for Argentinian cinema. Apart from Future Perfect, there was Matías Piñeiro’s latest, Hermia and Helena. It’s another of the director’s Shakespearean explorations, although the connection is less obvious than in some of his other films—that is, beyond the heroine’s plan to translate A Midsummer Night’s Dream into Spanish. Set in Buenos Aires and New York, this deconstructed romance explores its knotty crossings of amorous paths with Piñeiro’s characteristic intricacy, elegance and wit. Constantly signaling itself as a filmic construct, sometimes in willfully jarring fashion, Hermia and Helena is a reminder that, as much as any director working today, Pineiro is defined by a peculiar sensibility, rather than necessarily a style. While his intentions may be elusive, you feel that, from film to film, you want to spend time with him and his characters just to get the measure of his mysterious, leisurely (and I’m not sure I can think of a better noun) vibe. Even more enigmatic is another Argentinian film, Eduardo Williams’s The Human Surge, which caused its own surge of excitement and puzzlement. Structured as a kind of associative drift—imagine a global version of Slacker—it starts in Buenos Aires, where a young man has lost his job, skips online via a gay porn site to life in Mozambique, then moves via the innards of an anthill to the Philippines. That may be an accurate outline, but I’m not sure: there’s no obvious map for a film which seems to phase in and out of focus, one moment seeming scrappily thrown together, the next elegantly crafted, but always brazenly flouting stable criteria of plot and narrative. Beyond observations about the way that global connectivity at once connects and radically separates the economically excluded, it’s hard to know entirely what Williams is gesturing at. But he means business, and this perplexing film will resonate.

The Idea of a Lake I was less taken with another Argentinian feature, the more conventional The Idea of a Lake by Milagros Mumenthaler, who won the Golden Leopard here in 2011 with Back to Stay. Still, Mumenthler’s film has a strong sense of its own political and personal agenda. It’s about a young woman working on an art project involving memories of childhood holidays and the fate of her father, one of Argentina’s disappeared. Mumenthaler addresses familiar themes in a familiar self-reflexive way, but her film also uses some oddball ploys that you could either call audacious or misguided—such as a childhood fantasy sequence set to Neil Diamond’s “Song Sung Blue.” Overall, though, The Idea of a Lake is a bold, focused venture, and it makes for an interesting comparison with a film by another woman director, Thailand’s Anocha Suwichakornpong. Like The Idea of a Lake, By the Time It Gets Dark—Suwichakornpong’s second feature, following 2009’s Mundane History—is about a female protagonist exploring a particular place in order to examine personal and national trauma. It’s ostensibly about a filmmaker interviewing a heroine of hers, a 1970s student activist, with a view to dramatizing her experiences. For its opening stretch, Suwichakornpong’s film uses familiar film-within-a-film tropes in what seems an incongruously lyrical style, given the theme of state violence. But as it continues, with characters proliferating and levels of reality fragmenting wildly, the film’s own status as an intransigently enigmatic art object takes the upper hand. This film was one of the more bracingly unstable things on show this year. Finally, two artists’ films of note. One is Ascent, by Amsterdam-based Fiona Tan—which I’ll be very brief about, because I had the pleasure of collaborating on her last film. This is a poised contemplation of the lore of Japan’s Mount Fuji, past and present, with voiceover text (Tan and Hiroki Hasegawa) over still images of the mountain, offering a poetic contemplation of geographies physical and cultural. The other features more voice than image: in Douglas Gordon’s moving I Had Nowhere to Go, Jonas Mekas—sometimes over non sequitur shots, often over dark screen—reads his reminiscences of life as a displaced person in Europe in World War Two and as an immigrant in Brooklyn. Mekas’s wit and tenacity emerge deliciously in a hypnotic, tender piece, all the more powerfully so the more laconic he is. One diary entry, in those stately, wheezy tones: “Got fired. Ha—ha—ha!” If that’s not an inspiring declaration of defiance for today’s hard times, nothing is. Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.