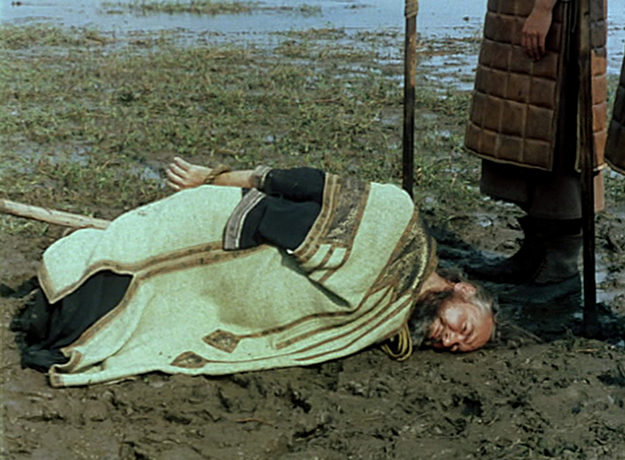

Moses and Aaron QUITE A LOT OF PENT-UP ANGER… January 3, 1994 Returning from a rather long journey, we found the first issue of Nuances, for which we thank you. Nowadays it is rare to read concrete, precise, documented—and impassioned—things. Thank you. But how depressing at the same time! In 1975 we did a tour of the USA, where we were invited because our film Moses and Aaron was playing at the New York Film Festival and some universities asked us to come with some films. We chose these universities based on museums where Cézannes were to be found, and that’s how we saw for the first time those of the Barnes Foundation that we have just seen again, in part, at the [Musée d’] Orsay. We had to hitchhike to get back into the city because it’s true that there is very little public transportation that services the area around the foundation, but we were happy to have finally found a museum where it was considered normal for people to come to the paintings—which can always be achieved, if you really want to, even with hardly any money (we’re the proof!)—and not the paintings to the people. That’s something that’s all over with; as well as the refusal of reproductions, which certainly makes sense, since it’s a truffe (“a fraud”), as the Italians say, to make people think they have “seen” (and thus taken possession of) a painting, when without the matter, they have only a shadow, a piece of information. At the Orsay, when we were preparing our film Cézanne, on August 15, 1989, we saw a piece of gum stuck to a Cézanne. I looked for half an hour for a watchman (excuse me, a security guard!) to let him know, my heart pounding because I was afraid of starting an avalanche: “protective” glass on the paintings… Once he was found, he told us he couldn’t do anything, only a conservator could take the thing off…. Eight days later, the gum was still there. Back in 1975, the first thing we did upon arriving in New York was to go to the Museum of Modern Art to see… Cézanne: a dazzling experience, and an exhausting one, too, because you can’t sit, and several hours standing, in deep concentration, to look, is tiring. Coming back from our tour all over the country, we had a day before our return flight, so we went back to MoMA, where we didn’t recognize our Cézanne. It was horrible: each painting was now under armored glass, and often damaged in the process (new little cracks, etc.).When we protested this madness, saying that it’s better to risk a—rare—act of madness than to make the paintings invisible—reflections, etc.—and surely damage them, we were told, grudgingly: It was a requirement of the insurance… You also know, I suppose, that the paintings in the Tate Gallery, in London, travel almost nonstop between there and the “branch” in… Liverpool! Facilitated by privatization. All the paintings are therefore under glass, completely invisible because the Tate doesn’t have enough money to pay for antireflective glass. The Basel Museum is the only “public” museum among those that we visited and where we filmed for Cézanne, where the protective glass is (almost) invisible, where the light is correct (as with the Tuileries, thanks to the light from the windows and the Seine), and where the paintings are hung straight, horizontally, and not tilting to the left or tilting to the right… […] In 1959, when we were preparing Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach, we saw, at the Staatsbibliothek in East Berlin, Bach’s manuscripts and scores, in particular the huge score decoratively handwritten by him, with the Cantus firmus in red, of the St. Matthew Passion. When we finally managed to get the money together to make the film, in 1966-67, we went back to see the scores again. There, too, we didn’t recognize them—what had happened? We were told that in order to protect the scores, they had been glued to canvas, forgetting that in the glue there was an acid that “ate” the paper. “But,” they added, “it’s not too serious; we have the microfilm…” Only, when the narrow-mindedness and the arrogance of a class and a century that believes itself to be “scientific” and more intelligent than prior centuries, and that is incapable of foreseeing the consequences and calculating the risks of its ventures in every domain is combined with the greed (or power) that leads Monsieur, for example, to consider the works of art brought together by Barnes as capital that must, by definition, return a greater value (and this goes for all the directors of state museums pushed by privatization, which is the equivalent of vandalizing common goods by the same bourgeoisie and by so-called promotional necessity); well, this is unrestrained pillaging and vandalizing. We cut the banana trees to eat the bananas and, after us, the Deluge. And I’m not even talking about what is happening in our field, still so young, the famous “restorations” of films—the refusal of any patina, because of the idiotic and arrogant idea that you can act as if time has not passed! Danièle Straub-Huillet, filmmaker