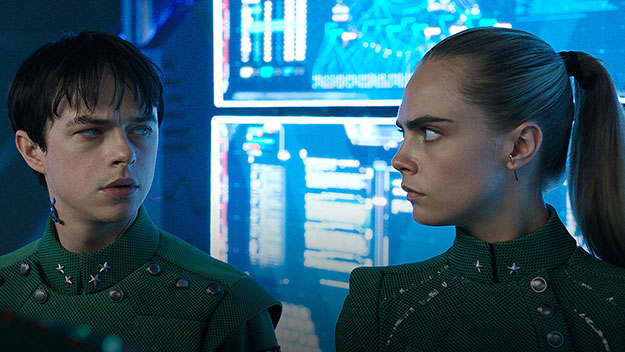

Luc Besson’s Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets, based on the French graphic novel series Valérian and Laureline by Pierre Christin and Jean-Claude Mézières, is a travesty of storytelling. But if Paris’s Bureau International des Expositions, which licenses world’s fairs, ever needs a visionary new creative director, I think they have one in their own backyard. Unlike so many hyperactive would-be blockbusters, Valerian is not like a visit to a theme park. It’s like gliding on a tramway through an international expo on the World of Tomorrow… and Tomorrow… and Tomorrow… . The action is meant to be edge-of-your-seat, but we end up leaning back to take it all in. It’s so bereft of narrative tension and emotion and refulgent with visual invention that it functions strictly as spectacle—before it stops functioning at all. The movie starts out witty, even mesmerizing. In its ruling conceit, Alpha, the “city of a thousand planets,” began with the U.S.-Soviet Apollo-Soyuz space mission in 1975. Two capsules docking grows into a space station and then into a satellite—and ultimately into a floating megalopolis. In the first of two awkwardly stitched prologues, we see astronauts and cosmonauts shaking hands. Then we tumble into successive mock-stately views of a multinational human crew greeting creatures from other worlds, whether they look comfortably humanoid or fiercely alien, organic or metallic. It’s all sweet and funny—a liberal and accommodating vision of the future, unfolding to the tune of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” (“Ground Control to Major Tom…”). In the next section, we meet the lithe inhabitants of the planet Mul. These pale-skinned, beach-dwelling super-mannequins, cousins to Avatar’s Na’avi, gracefully execute the daily rituals of their ocean-side paradise, including nature-loving prayers with a creature we later learn is called the “Mul converter,” a mini-armadillo that craps out pearls. Then the movie goes all scary and poignant as sulfurous clouds pock the atmosphere like upside-down twisters and war machines fall from the tarnished blue sky into the deep turquoise sea. Remember the little girl cruelly kept out of the rural bomb shelter in Frank Perry’s Ladybug, Ladybug? What happens in Valerian may be even sadder, when a beautiful princess can’t get into a shelter simply because its lock is broken. Valerian lurches from the humorous grandeur of the first prologue to the puzzling mysticism and tragedy of the second. It hits an abrupt low point when we meet our human heroes, Major Valerian (Dane DeHaan) and Sergeant Laureline (Cara Delevingne), special ops in the galaxy-hopping human army of the 28th century. From the moment we see them lounging on a beach, we realize that Besson has enlisted the wrong guy and gal for the job. We don’t buy DeHaan’s Valerian and Delevingne’s Laureline as futuristic Rangers or Seals. As special ops, they’re more optical than operational. DeHaan comes on like a surly young faux-DiCaprio: he tries in vain to swagger like a rocketing he-man. Delevingne (an actual supermodel who turned actress for Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina) acts petulant and entitled when she’s supposed to be centered and sympathetic. At first I thought, OK: Besson wants to keep the human characters blank, to set off the kaleidoscopic colors of his universe. But DeHaan and Delevingne don’t function even as fantasy stand-ins. They’re like hapless, pretty children. Their competitive banter revolves around his distrust of her driving. Is this all just a failed joke about the persistence of female driver stereotypes in the 28th century? Valerian tells her she’s the one for him, but Laureline is skeptical, knowing he’s had a string of conquests, especially previous partners. Theirs is a non-marriage of convenience. Besson is banking that we’ll root for these good lookers to get together. But they don’t have enough substance and genuine friction to generate sexual tension. How could a director who lavished so much attention on every little beastie and every inch of his universe have made such a mistake with his writing and casting of the central characters? If they appeared in a remake of The Black Hole, they’d be mistaken for the title characters.

They don’t connect with any of the other would-be humans in the film, either. Their first action sequence is a virtuoso mix of alternate and virtual reality. Valerian and Laureline travel to a desert planet where they must wrest the last surviving Mul commuter from a Jabba the Hutt–like bandit in a bazaar that exists in another dimension. Besson pulls off extraordinary shifts between the arid landscape as it “really” is and the dizzying, teeming casbah it becomes when customers put on special headgear. We succumb to the eerie, vertiginous feeling that we’re living on a 360-degree stage in front of an all-encompassing green screen. But neither Valerian nor Laureline gets any vibe going with the funky, eccentric commando unit that makes their mission possible. And they appear heartless when they escape a huge snapping sand dragon with nary a backward glance to see who else survives. The rest of the movie amounts to a Journey to the Center of the Earth, Alpha edition, as Valerian and Laureline penetrate into the bowels of the city of a thousand planets. Hancock’s Minister of Defense catalyzes the movie’s shred of plot when he orders them to protect a human commander (Clive Owen) as he investigates a radioactive zone that’s spreading out from Alpha’s core. What the movie lacks, besides an emotional center, is a good McGuffin to give this plot some drive and focus. The commander’s search for the cause of the “radiation zone” is too flimsy. The commander himself becomes the McGuffin when he’s kidnapped, but Besson gives the redoubtable Owen so little to play that we don’t miss him when he’s gone. The key to the whole sprawling movie would be that double prologue, if only Besson had the dexterity to thread the opening images and themes in and out of Valerian and Laureline’s headlong adventures. Occasionally Besson’s extravagant brand of Pop Art generates some visceral oomph. In one piece of comic-book kapow, Valerian takes a shortcut through multi-walled Alpha by crashing through one barrier after another, helmet first, like a human battering ram. The act itself is electric, like the Navy SEALs in Peter Berg’s Lone Survivor deciding that the quickest way to come down a cliff is to leap from it. The payoff arrives when Besson reveals a new world behind each wall, as Valerian hurtles from the galaxy’s biggest, brightest orchard to an eerie artificial fjord, and from the inside of what looks like an infinite gumball machine (the balls could be the nuclei of neurons) to the bottom of a brackish green sea.

Nothing connects, though incidental pleasures crop up along the way. The Doghan Daguis, a trio of winged, alien platypuses, can stand on their own splayed feet but can thrive only as a threesome. They boast a Lewis Carroll–like lunacy, cunningly brokering information and finishing each other’s thoughts, not because of some intuitive bond, but because their brains are wired that way. When Laureline is kidnapped and Valerian searches for her in “Paradise Alley,” one woman of the boulevard recalls Jessica Rabbit. Rihanna ignites the screen with sensual bravado as a burlesque entertainer named Bubble, starting her showcase number as if she were Liza Minelli’s Fräulein Sally Bowles. Bubble turns out to be a super-swift quick-change artist, transforming herself into a provocative nurse and other porny fantasies. Can Rihanna act? You bet. Bubble knows Shakespeare and can movingly quote Paul Verlaine (“I’m afraid of a kiss / Like a kiss from a bee”). She’s touching and amusing when she unveils her true self as a big blue cuttlefish of a shape-changer—and allows Valerian to hide inside her as she takes on thick-legged, pot-bellied, long-necked, and google-eyed form to rescue Laureline from a barbaric king. (We later discover that the spirit of the Mul princess has been hiding inside Valerian, but Besson and DeHaan do nothing emotionally expressive with these in-and-out identities.) The film derives much of its plot and many of these creatures from the sixth volume of Christin and Mézières’ series, Ambassador of the Shadows. (Besson contends that only 30 percent of the fantastic beasts come from Ambassador; most of the ones he prominently features have their basis there.) We feel the director’s love for it—and that may be the problem. He’s over-charmed by the material, and it blinds him to the limitations of the original. Christin and Mézières, at least in Ambassador, are declarative and expository storytellers. That’s not a big drawback in a form that allows them to set the stage in captions. An alternately wispy and brittle plot doesn’t fatally damage a graphic novel filled with extravagant or grotesque images that we can savor at our leisure. The comic-book makers are sure to intersperse panels stuffed with speech balloons and dynamic, spectacular spreads. And at 48 pages, the silliness doesn’t grow oppressive—it can even be infectious. Like Robert Rodriguez in his Sin City movies, Besson has miscalculated how much aesthetic distance there is between a comic book and a comic-book movie. Apart from all the delightful filigree, the fun gets lost in translation. Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.