Warren Beatty’s witty, frisky ramble through 1950s Los Angeles, Rules Don’t Apply, maneuvers Howard Hughes (Beatty) and two young Hughes employees, chauffeur and would-be real estate mogul Frank Forbes (Alden Ehrenreich) and contract starlet Marla Mabrey (Lily Collins), into an unlikely triangle. Beatty has set the film in 1958, the year the writer-director himself, like his fictional fellow Virginian, Marla, settled in Hollywood. Beatty has been promoting this picture as a comedic attack on Eisenhower-era Puritanism: Marla, “a Baptist nun” (as Hughes derisively calls her), thinks Frank is a married man in the eyes of God because he slept with his hometown Fresno fiancée. (His betrothed feels that way, too.) For Marla, to pursue a romance with Frank would be to “steal” another woman’s husband. The movie is more seductive and expansive than a satire of 1950s mores. It’s about how the Hollywood Dream became the American Dream, and why that was a good thing—partly because movies did undercut American Puritanism, but also because they epitomized the glory of self-creation, of choosing who you get to be in the big wide world rather than falling into your parents’ rut. Rules Don’t Apply conveys this reality-based fantasy, this wish fulfillment with a kick, in the form of a blithe, unruly entertainment. This isn’t the full-scale portrait of Hughes that fans have been expecting from Beatty for roughly four decades, yet he packs unexpected poignancy and laughs into his sideways portrait of the billionaire. Hughes dips in and out of the other characters’ lives like a haywire deus ex machina, creating as many problems as he solves. The film’s appeal comes from Beatty’s ability to see the slapstick tragicomedy in the figure of this cock-eyed visionary—codeine-addicted, narcissistic, self-destructive and destructive. The antihero functions for the hero and heroine as a catalyst and an obstacle. He’s both an inspiration and a one-man cautionary tale. Everything about the film is lightly ironic, from the title down. Hughes operates like a pre-Internet disrupter and an anti-Establishment maverick, whether as a moviemaker (addicted to watching his action milestone Hell’s Angels), an aviation pioneer, an industrialist with sensitive government contracts, or the founder of Trans World Airlines, which he tries to bring into the jet age. (His lack of corporate support stems partly from his refusal to appear before the board of directors, communicating with them only by telephone.)

When it comes to managing his stable of 26 aspiring actresses, though, this rule-breaker is all about rules designed to keep them toned and healthy, ready to do his bidding and nobody else’s. The movie scrambles together incidents from every part of Hughes’s life, including the flight of his fabled giant wooden transport plane, the Hercules H-4, or “the Spruce Goose,” and his fight to retain ownership of TWA. Rules Don’t Apply starts with a quote from Hughes, “Never check an interesting fact,” along with the admission that names and dates have been changed. Still, the biography that served as a basis for Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator (Howard Hughes: The Secret Life) contains a description of the starlets’ protocols that Beatty follows to a T: The appropriate actress would be given the use of an elegant house in Beverly Hills or Bel-Air, with a maid. At exactly 7 a.m., she must rise and take a shower and make up. At seven-thirty, the maid would serve her breakfast. At eight, a driver would take her to acting, dancing, and singing lessons. In the afternoon, she must rest or watch TV. Shopping was permitted once a week. In the evening she would go to one of six restaurants Hughes specified. She was forbidden to date. A driver would be her companion for dinner. … The drivers were told never to negotiate bumps in a road at more than two miles an hour as the jolt to the automobile might cause the girls’ breasts to sag. Working from a script with a story by Beatty and Bo Goldman (Melvin and Howard, Shoot the Moon), Beatty illustrates these rules as if thumbing the pages of a deluxe flipbook. Credit his master cinematographer, Caleb Deschanel, whose images are nimble and airy and also deeply evocative. The daylight colors boast a rare soft gloss, as if the smog has tenderized the spectrum. Early on, this film’s visual impact is the screwball equivalent of hearing Pat Boone sing “April Love.” It’s low-key fun to get acquainted with the earnest, ardent Frank, who peruses books on economics partly to keep his mind off Marla. But Ehrenreich’s intensity would be tiresome and his resemblance to a young Leonardo DiCaprio too jarring were he not palpably responsive to Collins’s Marla, who manages to be fresh-faced and fascinating, resembling Elizabeth Taylor one moment, Audrey Hepburn the next. Collins conveys a buoyant naivete; Marla is unworldly but not dumb. She may have been crowned the Apple Blossom Queen back in Virginia, but she says it’s a talent contest, not a beauty pageant, and what she really wants to do is write songs. When she tells Frank she knows she’s not buxom or overtly sexual like most other aspiring Hollywood starlets, he tells her she’s “an exception—the rules don’t apply to you.” And she turns that sentiment into a sweet, conversational song that she sings once quietly and authentically to Frank and once drunkenly and emphatically to his boss.

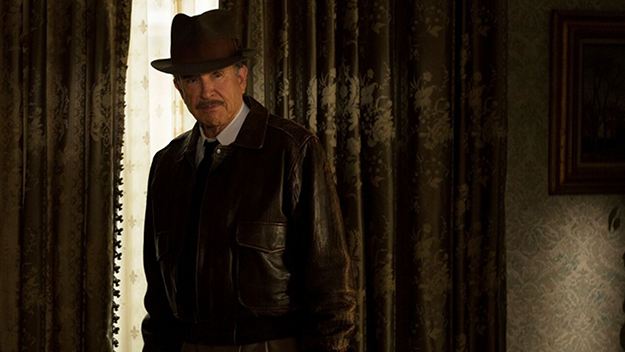

In her gumption, Marla takes after her electrically wary mother Lucy, who keeps the movie’s comic engine running with her keen matriarchal intuition and with Annette Bening’s crackling timing in the role. Bening gets a huge laugh simply by saying “I forgive you” when Frank says that he’s a Methodist. (The Mabreys are Baptists.) Lucy senses that Marla might never meet the elusive Hughes and that he might not be the answer to either her or Frank’s dreams. Luckily, when Bening leaves the picture, her real-life husband enters it and picks up the slack. Beatty has not been this intensely entertaining and focused (even when his character is out of focus) since Bugsy (91), and he’s learned from Barry Levinson’s direction and James Toback’s script for that film how to imbue a functioning psychopath with demented intrigue, even charm. Hughes is as incongruously and humorously childlike as he indulges his yen for Baskin-Robbins’s banana nut ice cream as Beatty’s Bugsy Siegel was while questing for self-improvement by reciting tongue twisters to improve enunciation. Hughes and the gangster Bugsy Siegel are similar mostly in their determination to see their fantasies ripen, whether it’s Hughes proving his Spruce Goose can fly or Bugsy fulfilling his vision of the Flamingo Hotel as a glittering American monument to gambling of every kind. They both want to hang on to what they build. Hughes’s illusions and desires are more open-ended than Bugsy’s crusade for “class” and self-improvement. For Hughes, not even the sky is the limit, as he takes the wheel of a DC-3 and cuts off its propellers for a proper glide. At times, Beatty plays Hughes like a mischievous vampire, always veering into the shadows, and Deschanel partners him beautifully, lighting his night-time meetings with Marla so that we, like them, must strain to make out how he looks and what he’s thinking. At other times Hughes is just an aging man with fading faculties. He knows that he’s prone to repeating himself, and he’s worried that others will find him insane—he even fears that he actually is.

Rules Don’t Apply has the satisfactions and the limitations of old-fashioned cinematic engineering. Every little incident or prop clicks together, like Marla’s song or the emerald ring that Hughes puts on her finger. But the narrative machinery chugs on after the comic possibilities have been exhausted and some dramatic depths have been ignored. It takes too much locomotion to bring Frank and Marla into more intimate relations with Hughes. Still, the movie displays an unexpected lyricism, both in some daring oddball moments—like Frank and Hughes taking a long walk down a pier that ends with them sharing burgers on a bench and staring at the Hercules H-4—and even more in the climactic encounter of the two men and Marla, which causes a bed-bound Hughes to reckon silently with what went wrong in his life. As Hughes, Beatty alters his moods like a quick-change artist. His superb changeability elicits some jolting surprises from Collins. She’s hilarious and touching when Marla decides to take her first drink while alone with Hughes, then sings “Rules Don’t Apply” to him. Cast members in roles large and small respond with jolts of energy to Beatty’s provocations, including Alec Baldwin and Oliver Platt as increasingly infuriated businessmen, and Steve Coogan as a pilot panicked by Hughes’s rusty daredevil aviation. No one gains more from Beatty’s attention than Matthew Broderick, who is uncannily good as a senior driver who wears himself out anticipating Hughes’s every wish. He and Beatty turn the two words “is” and “was” into a comic-opera duet. Beatty frames the movie with a fictionalization of the telephone press conference Hughes held to discredit Clifford Irving’s fabricated Hughes autobiography. In the movie Hughes keeps the journalists waiting in a Los Angeles conference room while he lies in bed behind a curtain in an Acapulco hotel room. It’s a perfect pop-poetic touch. “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain,” said that old trickster, the Wizard of Oz. As Beatty plays him In Rules Don’t Apply, even when we can’t see Hughes, we must pay attention to the man behind the curtain. Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.