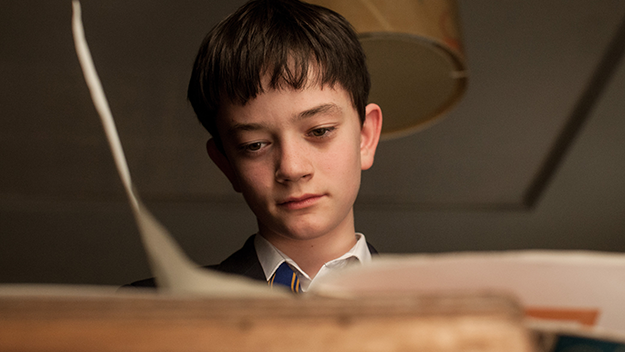

Dennis Potter, the author of The Singing Detective, composed his scripts in longhand because writing was as physical and sensual for him as it was aesthetic and cerebral. The opening credits of A Monster Calls, J.A. Bayona’s film version of Patrick Ness’s Young Adult novel, start with the image of a pencil drawing on paper. From that point on, the whole movie is comparable in poetry and impact to Potter’s pop fantasias. The usual phrase for Bayona’s controlled expressive style is caméra-stylo, but stylo sounds a bit off to me—we really feel as if Bayona filled this movie out with an artist’s stick of charcoal. With its open-ended expansiveness and mastery of a child’s point of view, watching A Monster Calls gave me the reverberating pleasures I had watching Potter’s Lewis Carroll film, Dreamchild (directed by Gavin Millar). The author’s sensibility and the director’s flights of fancy galvanize a poignant combination of psychological realism and irrational wonders. Ness adapted his own book about a few days in the life of a contemporary British lad, Conor O’Malley (Lewis MacDougall), as he faces traumatic grief and peril: the grave illness of his single mother (Felicity Jones), the pounding fists of a schoolyard bully, and the recurring visits of a tree monster (Liam Neeson) shortly after midnight. What makes Ness’s deft, inventive screenplay all the more remarkable is the way it opens up the narrative to exploit the visions of director Bayona and Jim Kay, the book’s illustrator. (The tangled profusion of his townscapes and landscapes, and his ability to unify contrasting styles with charged poetic moods, put Kay in a class with Arthur Rackham, the renowned British illustrator who influenced the look of Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth.) In a masterstroke unique to the film, we learn that Conor’s mom had planned to go to art school when she became pregnant. At age 12, Conor is already a precocious artist. When Conor takes to his drawing board and sketches out a frame, it has the same shape as his bedroom window, which overlooks a melancholy landscape with a single yew tree on a hilltop. The tree spurts up and out to become his monster. Both the boy’s creative impulse and his psychological need summon it to life. Conor’s pencil marks and brushstrokes pay homage to the alternately rugged and feathery textures of Kay’s protean vision of the novel’s scenes and characters. (The book’s illustrations are black and white; the movie renders the story in superbly modulated color.) Bayona incorporates startling handcraft into his digital effects with an uncanny instinct for what feels naturally supernatural, as befits a protégé of del Toro. Bayona’s fluid vision and concentration on his actors make us feel as if we’re entering Conor O’Malley’s universe, then tumbling down into its depths.

The movie begins with Conor’s vision of an earthquake in a graveyard. The monster insists that Conor will provide the details of his nightmare. We’re so in tune with the boy that we never think the monster is his nightmare. This film boasts an imagistic density to match its mounting heartbreak. It keeps us off-kilter about the reality of the monster and the literal truth about what happens when the boy is with him. As the tree asks, couldn’t the monster be real and everything else be the dream? The tree giant says that he intends to relate three stories before the boy tells him a fourth story, which will reveal Conor’s “truth”: his tightly guarded secrets and the troubling feelings that bother his sleep. The film rouses fairy-tale expectations, then refuses to satisfy them conventionally. The promise of three stories—and multiple visitations—echoes Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, and the three wishes the genie grants Aladdin in The Thief of Bagdad, and even the three wishes in “The Monkey’s Paw.” The monster’s stories follow no formulae and eschew easy morals. Just as Conor cannot predict the shape or outcome of the plots, we cannot anticipate how each tale will look or move or end. What’s horrifying to the monster is any taint of a simple, moralistic attitude, especially on the boy’s part. Conor wants the tree to act like a fairy godfather who will satisfy his heart’s desires—most of all, saving his mom. The monster, we gradually learn, wants to prod the boy into emotional honesty and insight.

The monster brews up period fables, one pitting an innocent prince against his evil step-grandmother, another a righteous (or self-righteous) pastor against a mysterious herbal apothecary. Conor and Bayona envision them in vivid profiles and splashy, vibrant watercolors, as if the boy himself is conjuring them from his own sketch kit and palette. The giant uses these storybook figures to undercut clichéd messages about virtue triumphing over vice, and to prevent Conor from viewing real people as stereotypes—from seeing, for example, his youthful, svelte, all-business grandma (Sigourney Weaver) as a vicious queen. Conor gets progressively more frustrated. By the time the monster comes to the third story, about an invisible man who no longer wants to be unseen, Conor’s own character merges seamlessly with the protagonist: this tale swiftly becomes a launch pad for Conor’s rocketing destructive urges. In A Monster Calls, the road to self-knowledge is bumpy and painful. Conor climbs that road only after he gathers how the stories all bleed into real life. Happily, A Monster Calls goes beyond debunking fairy-tale bromides. Conor’s father (Toby Kebbell) has started a second family in America. In one of the film’s funniest and most touching scenes, he tells his son, in a rare get-together, that life is all about living “messily ever after.” Nothing could be messier than the boy’s contradictory feelings. Even more than Ness’s novel, the movie testifies to the power of artistic wizardry. In an organic payoff that packs an emotional wallop, Conor comes to comprehend his mother’s enduring legacy—one that encompasses a 16mm print of the 1933 King Kong and her own painterly daydreams. She has bequeathed her own rough magic to her son. Bayona’s actors connect and disconnect with heartfelt veracity and unexpected sophistication. Jones, so impersonally heroic in Rogue One, here fills the screen with a weary, slightly bucktoothed beauty, investing Conor’s mom with an understated tenderness vastly more potent than tear-jerking histrionics. Kebbell, as the father Conor barely knows, depicts a rueful parent struggling to bridge gaps, most successfully with humor, while Neeson, acting in a motion-capture outfit, imbues the tree monster with another kind of paternal character, rooted and combative, then fiercely reassuring. The yew tree in its monster form is 30 or 40 feet tall, and, with its boughs outstretched, nearly as wide. Few other contemporary actors boast the heroic stature to bring this phantasm to life—or possess a voice resonant enough to fill its outsize contours. Neeson suffuses the monster’s words with heat and, more important, warmth. As an audiovisual construct, this movie lives up to Wordsworth’s praise of “the Yew-tree” at Lorton Vale: “This solitary Tree!—a living thing / Produced too slowly ever to decay; / Of form and aspect too magnificent / To be destroyed.”

On his own more diminutive scale, MacDougall never coasts on wistfulness or melancholy. This young actor captures the fury and wounded pride of a boy who feels both his mother and his own youth slipping away. He and Weaver are perfectly matched antagonists: each embodies a formidable tenacity as their characters refuse to give an inch. Their rigor and honesty make their cathartic moments surprising and profound. Perhaps even more distinctive, though, is the ambiguous relationship MacDougall builds with James Melville as Harry, the taller, stronger boy who bullies Conor. Harry responds to the angry challenge in Conor’s eyes. He gradually realizes, without benefit of any discussion, that Conor wants him to mete out punishment. Every bit of this film is expressive. When Conor sits distracted in a math class, we overhear the teacher pondering the question, “What is the mathematical function or thing which describes things where the rate at which they change is proportional to their magnitude?” The magnitude of Conor’s traumas will change him quickly and forever. The movie is so superbly crafted and empathic, it takes us along with him, every step of the way, to the outer limits of damnation and enchantment. Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.