As a filmmaker and a composer, John Carpenter is superbly efficient, insisting that he recorded nearly all of his own scores simply because he was “fast and cheap.” Without any formal musical training (save for a few childhood violin lessons), Carpenter has always collaborated with other musicians, generating entire soundtracks out of quick improvisations. Last month, Sacred Bones Records released the second volume of Lost Themes, Carpenter’s original recordings with his son, Cody Carpenter, on keyboards and godson Daniel Davies (son of The Kinks’ Dave Davies) on guitar. The trio is supported by members of Tenacious D’s backup band, and this sextet will kick off their international tour next Friday in Los Angeles, with a New York show scheduled for July 8 at the PlayStation Theater. The timing of Carpenter’s first live tour and the second Lost Themes record release is opportune, amid an intensifying revival of Carpenter-esque music. Recent genre directors like Ti West, Adam Wingard, and David Robert Mitchell have mimicked elements of Carpenter’s visual style and sound, while the 2011 release of Nicolas Winding Refn’s throwback Drive helped cultivate a parallel strain of fetishistic nostalgia that both idolizes Carpenter and the neighboring aesthetics of ’80s car culture, television animation, and video games. Endless micro-genres under the umbrella of Synthwave (or Retrowave) such as Chiptune, Outrun, 8-Bit, and Darkwave all flourished in the post-Drive 2010s on MySpace, and now include mostly solo acts with names like Perturbator, Lazerhawk, Carpenter Brut, Power Glove, and Com Truise. The underground wave has grown so widespread that the second-annual SYNTHZILLA festival is set to take place in France this coming fall, and funds for a documentary on the movement are currently being raised on Kickstarter with a pledged goal of $169,000 (one-half of the proposed €300,000 budget). The Kickstarter video for the project, The Rise of the Synths, follows a character called the “SynthRider” who sports a fake “They Live” tattoo across his throat, a “Suspiria” tattoo on the back of his neck, and a John Carpenter Bobblehead doll on the dashboard of his DeLorean. In general, the new Synthwave bands adopt a Knight Rider look in their album art and music videos and perfectly replicate old synthesizer tones with nary a trace of Carpenter’s rock-music roots. Meanwhile, boutique record labels like Mondo and Death Waltz perpetuate Carpenter’s original sound with new reissues of his early soundtracks.

Halloween III: Season of the Witch The second Lost Themes album nudges Carpenter’s music into the present from the opposite direction, with more traditional rock instrumentation and loud acoustic drumbeats, while Carpenter’s signature one-handed keyboard melodies maintain pride of place. Cody Carpenter and Daniel Davies are both accomplished musicians capable of playing in different styles but defer here to the elder Carpenter’s well-known electronic/rock mode with familiar sequencing, heavy bass lines, deceptively simple melodies, and dirty synth plug-ins. Some of the cleaner, more complex keyboard segments, still in line with Carpenter’s borderline-proggy musical sensibility, likely reflect his son’s input. The younger Carpenter has stated that his primary musical influence is Vince DiCola’s soundtrack to Transformers: The Movie (86) and his keyboard work with his band, Ludrium, assumes an upbeat, heady style that alternates lightweight synth-pop with Keith Emerson riffs. The evident camaraderie of the Lost Themes family band recalls Carpenter’s earlier rock trio, the Coupe de Villes, which he formed at USC with his friends and artistic collaborators Nick Castle (screenwriter and the man behind the Michael Myers mask) and Tommy Lee Wallace (director of Halloween III: Season of the Witch and It). The Coupe de Villes occupied the spotlight once to promote their theme song for Big Trouble in Little China (86) with an incredible music video:

During his guitar-heavy streak throughout the ’90s, Carpenter briefly formed a one-off band with ex-members of Steely Dan and Booker T. & the M.G.’s called the Texas Toad Lickers to record the soundtrack for Vampires (98). A beautifully tinted, anamorphic-lensed film, Vampires suffers from an execrable script, penned by someone other than Carpenter and partially improvised by James Woods, who babbles alarmingly like Ted Nugent whenever he is allowed to speak freely. The Toad Lickers’ bluesy guitar and prominent pedal steel adjusts the perspective slightly, reframing some of the film’s failed witticisms and sexist violence as off-color examples of generic Western grit. Carpenter’s most rewarding collaborations were not with bands but with two distinguished synth programmers: Dr. Daniel Wyman and Alan Howarth. Carpenter first came into contact with Wyman at USC, where the Moog expert was teaching a course on synthesizers. After Carpenter composed the soundtrack for his debut feature, Dark Star (74), on his own, Wyman programmed the synthesizers for his next three films: Assault on Precinct 13 (76), Halloween (78), and The Fog (80). As Wyman tells it, he actually programmed all three soundtracks on one synthesizer, an expanded Moog modular Series III (with sequencers), overdubbing each synthesized instrument one layer at a time. No drum machines were used—the ominous clacking that plays throughout the main theme to Assault on Precinct 13, for example, was actually a modulated sequence created on Wyman’s Moog at his Sound Arts studios in Los Angeles. Wyman patched, tuned, and programmed the Moog under Carpenter’s direction, while the latter composed the dominant melodies such as the one for the title theme, which is a redo of the famous guitar line that plays throughout Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song,” pared down drastically to suit Carpenter’s stark taste.

Escape from New York Wyman and Carpenter are best known for their production of the sinister piano track in Halloween, which was influenced in part by Goblin’s Suspiria theme and Mike Oldfield’s similar one for The Exorcist, although the hurried melody adheres strictly to the 5/4 time signature that Carpenter learned from his father as a child on the bongos. Carpenter initiated his most prolific collaboration in 1981 with Howarth on the Escape from New York soundtrack. Howarth mostly carried out the same tasks as Wyman though he utilized a broader range of gear while Carpenter continued to dole out compelling melodies with the fewest possible notes. His keyboard lines would often repeat, invert, or climb dutifully up and down scales, egging on characters like Kurt Russell’s Snake Plissken or Rowdy Roddy Piper’s John Nada to stand down authority figures with clenched fists. Howarth and Carpenter’s final three soundtracks were their most sophisticated. Big Trouble in Little China became Howarth’s first foray into MIDI computer programming, while They Live (88) marked his first use of the Synclavier digital synthesizer to sample analog instruments like the harmonica, saxophone, and Carpenter’s favorite: blues guitar. Prince of Darkness (87) is now highly regarded by synth enthusiasts for its complex gothic score with choral samples that call to mind one of Carpenter’s great inspirations: the early soundtracks of Tangerine Dream.

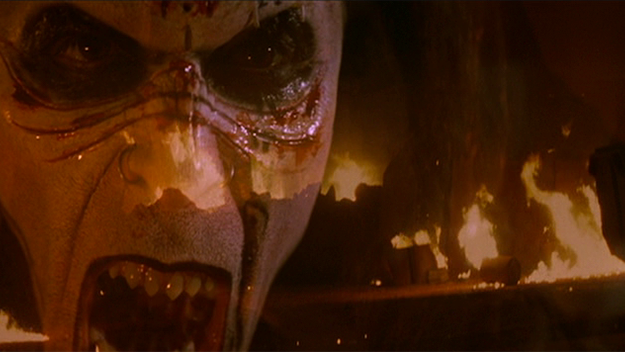

Ghosts of Mars Eight years post-Howarth, Carpenter hired composer Shirley Walker, who previously scored Memoirs of an Invisible Man (92), to revamp and expand the Escape from New York soundtrack. Carpenter wanted to aggrandize the sequel, Escape from L.A. (96), with orchestral rock, futuristic industrial percussion, heavy metal guitar, and spaghetti Western music. Walker and Carpenter pulled off the project as a team, but the film’s computer-generated effects were shockingly poor and out of date. I may be splitting hairs here between two films with comparably poor CGI, but I quite enjoy Ghosts of Mars (01) and consider it a nearly successful, B-movie-influenced camp film, less exhaustive than Escape from L.A. This has something to do with the onanistic heavy metal soundtrack, which better accompanies Ghosts of Mars than Walker and Carpenter’s commendable score for Escape from L.A. In this behind-the-scenes video, an exhausted Carpenter gently head-bangs and offers an encouraging thumbs-up in approval of the über-collaboration in front of him: members of Anthrax, Buckethead, and Steve Vai shred over each other like maniacs in a cramped recording studio. The scene on the monitor shows the film’s head villain, Big Daddy Mars, presiding over his face-painted minions with an inarticulate battle cry (his vocabulary throughout the film is limited to “RAH RAH RAH”). He isn’t exactly scary, per se, but that is beside the point. Don’t stop the riffs; this is a movie about alien ghosts on Mars.

Margaret Barton-Fumo is the editor of a forthcoming book on Paul Verhoeven and a longtime contributor to FILM COMMENT.