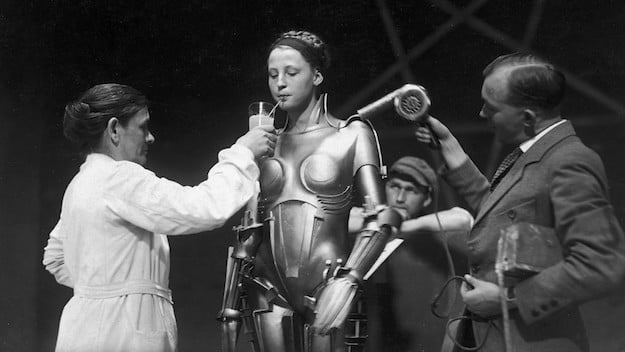

Production still from Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927) Directed by Fritz Lang, Metropolis premiered in 1927 to reviews like H.G. Wells’ that harped on the proto–science fiction film’s “sillier” nature. The genre in general does demand a featherlight suspension of disbelief. However, this story written at the height of futurism — about a teacher who becomes a beacon of hope for the proletariat before her likeness is stolen and etched into a “man-machine” for the nefarious purpose of controlling the working class — has influenced nearly 100 years of genre film, including some of the most important contributions to science fiction, from Logan’s Run (1976) and Blade Runner (1982) to Brazil (1985). It was also written by a woman. Thea von Harbou—who wrote the screenplay of Metropolis and a novel that elaborated on its ideas—is not an easy writer to celebrate without reservation. Though she was prolific and a luminary of genre film writing, having authored M, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, and Destiny, among countless others, her activity in the film industry under Nazi rule in the 1940s has cast a shadow over her immense output. Nonetheless, von Harbou is a godmother of contemporary sci-fi filmmaking, one of the first to commit to screen the unique and peculiar ways in which futurism and cosmic fantasies would affect female characters, and to ask the question: What is a woman’s place in an alternate time or inevitable future? Then came Leigh Brackett, whose pulp novels broke her into screenwriting with The Big Sleep, though she published a plethora of space-opera fiction stories throughout her career, spanning generations. When George Lucas called her up to write the script for what would become The Empire Strikes Back (1980), he didn’t even know she was responsible for The Big Sleep, let alone Rio Bravo, Hatari!, multiple Alfred Hitchcock Presents scripts, and even Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye. He’d just enjoyed her short fiction, which was full of radically fanciful creatures and romance, while other sci-fi writers of the time were taking on “harder,” more typically masculine subjects. Though Brackett died of cancer mere weeks after she handed in her rough first draft, the general arc is hers, as well as the style of playfulness amid catastrophe. Brackett made it okay for people to revel in love and romance in science fiction. An early cohort of Lucas, Steven Spielberg, also found kinetic energy when pairing with another women sci-fi writer. Spielberg met Melissa Mathison on the set of Raiders of the Lost Ark and found a kindred soul. He set her the task of writing a story about an alien that befriends a child, which would become E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982). The script was “done” by the time they got to set, meaning plots and characters had been worked out, but Mathison was a writer of curiosity and discovery and came to set every day with a notepad, following the child actors around and jotting down phrases, wordings, and emotional responses she witnessed, which resulted in realistic dialogue that grounded the picture. Some of the sweetest, most acute elements of E.T. come from Mathison’s special polishing, including the moment when Drew Barrymore’s Gertie examines the alien, then wrinkles her nose and whines, “I don’t like his feet.” Mathison found the day-to-day humanity amid the fantasy and wonder. On the fringes of sci-fi filmmaking, we have Lizzie Borden’s timeless pseudo-documentary hybrid Born in Flames (1983), about two rivaling factions of feminism led by guerilla radio jockeys, and the world they live in, which is controlled by mainstream media that belittles the concerns of women and people of color, and where even Leftist leaders seem out of step with their faux-Utopian rhetoric. The film is as entertaining and thought-provoking as it is a beautiful thing to behold, full of harshly contrasting light and performances raw with feelings of anger and disillusion. But it is Borden’s enigmatic writing style that buoys the film. As Richard Brody recently said, “[Borden] proves herself to be a far more imaginative and farsighted screenwriter than many celebrated Hollywood figures, because she sees the plot from a wide range of perspectives and circumstances, including one that she palpably views with hostility. Borden’s very sense of what constitutes a story . . . is as radical as the social politics that she asserts.”

Teknolust (Lynn Hershman Leeson, 2002) Of course, science fiction written by women can also be light fun, as exemplified in Susan Seidelman’s rom-com Making Mr. Right, starring Ann Magnuson and John Malkovich. The 1987 yarn takes a hard-right screwball turn and imagines a world in which a woman can essentially build the man she wants, free of emotional or societal baggage about how love and relationships should work between the sexes. The film almost seemed a response to the sexist tropes of the wildly popular Weird Science (1985), in which teen boys make their dream girl; so many sci-fi comedies of that time were both written by men and centered men in crisis trying to create perfection, like Harold Ramis’s Groundhog Day and Multiplicity or Joe Johnston’s Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and Joe Dante’s Innerspace. When a woman writes a sci-comedy, it tends to stand out, like Jac Schaeffer’s under-sung indie Timer, set in a world where everyone has the ability to activate a little timer that counts down to the exact moment when they will meet their soulmate. In the 2000s, the Wachowski Sisters’ Matrix trilogy was an obvious watershed for science fiction. Experimental artist-filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson was one of a handful of women writers to draw inspiration from those blockbusters, embarking on a complex effort to explore the intersections of sex and technology, albeit on a comparatively lower budget. Her beguiling Teknolust (2002) stars Tilda Swinton as scientist Rosetta Stone. Rosetta clones herself three times, and these poor automatons must continually seek out and ingest a Y chromosome via semen to survive. Unfortunately, this dooms the donors, who are left with an inescapable virus that infects both them and their computers. With its eye on sex work of the future, its embrace of connection amid commodification, Teknolust is a forebear to recent Netflix hit, Cam, written by Isa Mazzei. The key difference being that Cam is science fiction of the present. In recent years, women have begun to embrace writing sci-fi in larger numbers. Lucile Hadžihalilović’s gorgeous, unnerving Evolution (2015) subverts gender expectations in a coming-of-age tale about a group of boys mysteriously raised on an island of women. (It’s also an excellent companion piece to her earlier film Innocence.) And then there’s Danishka Esterhazy’s Level 16 (2018), about a boarding school for girls that’s housed completely in a windowless building with the grimy gilding of a derelict hospital. The film examines feminine archetypes in opposition to one another. And not afraid to inflict emotional terror, Claire Denis’ High Life depicts unimaginable cruelty as a space barge full of inmates floats madly toward a black hole, questioning the ethics of our technology in an increasingly de-empathized environment. What’s exciting about the future of women’s sci-fi writing in film, however, is that it may finally become inclusive. Julia Hart’s Fast Color, for instance, centers on three generations of black women who harbor a power they must keep secret from society, lest it destroy them. On the television side, sci-fi fans have more to look forward to, with Vic Mahoney writing the adaptation of Octavia Butler’s Dawn and Nnedi Okafor and Wanuri Kahiu’s adaptating Butler’s Wild Seed. Since Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein pioneered the genre, sci-fi has been ready for women writers to take it back and make it their own. The future is female and will likely go where no man has gone before. April Wolfe is formerly lead critic for LA Weekly. She currently hosts the Switchblade Sisters podcast, and has written for the Village Voice, AV Club, the Washington Post, and The Wrap.