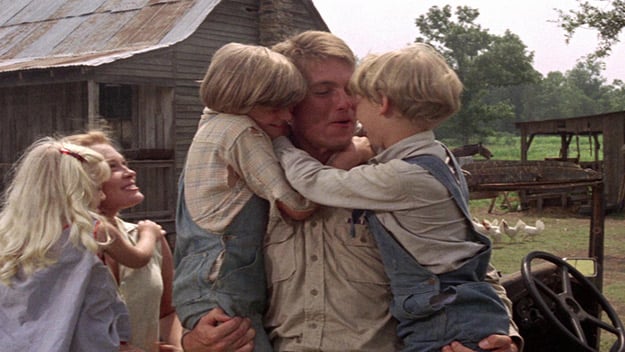

Hurry Sundown When you think of Hollywood and race in 1967, what comes to mind? Perhaps it’s that year’s Best Picture winner, In the Heat of the Night, or Jim Brown in The Dirty Dozen, or the box-office run that made Sidney Poitier, for a brief time, the number one draw in the country. But the industry’s attempts to reflect the day’s headlines were not categorized by landmark moments so much as by fits and starts, good intentions, well-meant bungles, compromises, and small steps forward. In the early spring of 1967, directors Otto Preminger and Martin Ritt, neither one an esthetic revolutionary but both emblematic of a genuinely well-intentioned, forward-looking brand of Hollywood liberalism, each brought explorations of race to the screen. One was an infamous flop, the other a modest success. And both illustrate where the industry was in 1967, and how far it still had to go. First, the flop—Hurry Sundown, a long, loony, luridly entertaining melodrama that is not good, but still well worth a look as a fascinating, one-of-a kind intersection of several about-to-be-huge careers, and as a lesson in how wide the gap between intention and execution can yawn. As background, it helps to remember that in the prior decade or so almost a dozen Tennessee Williams adaptations had reached the screen; that hothouse combo of alcohol, accents, sexuality, secrets, and actresses in slips was practically a film category unto itself. But by the mid-1960s, the movies, and Williams, were almost out of material, and the result was low-end variations on familiar themes like This Property Is Condemned, Arthur Penn’s The Chase, and, at the tail end of the subgenre, this film. Hurry Sundown, which drawls and drapes its way over nearly two and a half hours, intertwines, in a style that would later become a hallmark of prime-time television soaps, the stories of three Georgia families: a boozing heiress (Jane Fonda) whose opportunistic husband (Michael Caine) wants to develop some valuable land that she may or may not own, and the two subsistence-farming clans that stand in his way, one a white couple (John Phillip Law, soon to be of Barbarella, and Faye Dunaway, in her first year in movies), the other a black man (Robert Hooks) and his saintly, dying mother (Beah Richards). If that cast doesn’t make you widen your eyes and imagine some weird possibilities, what if I throw in Burgess Meredith as a bigoted judge, George Kennedy as a sheriff, and Diahann Carroll as a schoolteacher? Or mention the scene in which Fonda basically yells Richards into her grave?

Hurry Sundown The central question toward which Hurry Sundown ambles is: can poor white people put aside racial animosity to partner with poor black people against a common class enemy? That’s not an unsophisticated topic for a movie to explore in 1967 (in fact, it sounds a lot like a Bernie Sanders campaign pitch), but Preminger’s relationship to the subject, and to his black characters, was a good 25 years behind the times. Richards, who would be seen a few months later in the role in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner that would win her an Oscar nomination, cannot redeem an ineptly written mammy stereotype, and any goodwill Hurry Sundown might have accrued (which isn’t much) is demolished by a scene in which, before the film’s climactic showdown, the black characters gather in a shack….to sing the title song. Variety murmured that the moment was “too much like the darkies-are-a-singin’ discredited racial stereotype,” and Judith Crist began her horrified review, “Gather roun’, chillun, while dem banjos is strummin’ out ‘Hurry, Sundown’ an’ ole Marse Preminger gwine tell us all about de South,” going on to remark that “it stands with the worst films of any number of years.” There are, to put it kindly, several other problems. While Fonda (just before her Barefoot in the Park breakthrough) and Dunaway (warm, beautiful, fleshier than the movies would ever allow her to be again, and at 25, remarkably credible as the mother of a 12-year-old) both have affecting moments, Caine as a young Southerner is defeated by the accent and the character, Law is defeated by his inability to act, and all of them are defeated by a bellowing director who didn’t realize he was wrestling with a dud of a script. Nonetheless, Hurry proved to be a significant milestone in several careers. The film was shot in Louisiana, where, Carroll told a reporter during production, “You could cut the hostility with a knife.” Local restaurants and laundromats refused service to black crewmembers, and at night she would “cry my eyes out…down here the terror has killed my taste for going anywhere.” For Fonda, the shoot precipitated a moment of political awakening: after a newspaper ran a photo of her kissing an eight-year-old African-American boy, she wrote in her autobiography, “All hell broke loose. Shots were fired into the production wagons …. I listened to conversations between Robert Hooks, Beah Richards and others following the shooting incident: about a burgeoning ‘black nationalism’; about Stokely Carmichael calling for ‘black power’; about a growing sense that blacks had only themselves to depend on.” Fonda realized, she wrote, that, having spent the last couple of years in France, she had missed “a sea change in the civil rights movement.” An activist was born.

Hurry Sundown As for Dunaway, who Caine says became a particular target for Preminger’s wrath, the shoot reset her career. She had come from New York theater and signed a six-picture deal with the director in the waning days of the star-contract system. But after one too many incidents in which he “turned on me like a mad dog and went at me,” she called her lawyers. “It cost me a lot of money not to work for Otto again,” she wrote in her autobiography. “I paid him. I paid his attorneys. I paid my attorneys.” It worked: Dunaway was freed from her contract. Instead of making Preminger’s next picture, Skidoo, she signed to costar in Bonnie and Clyde. Hombre’s production was considerably less dramatic. Ritt and his star Paul Newman had worked together several times over the previous ten years, most successfully on 1963’s great modern Western Hud, so a reteaming seemed only natural (the one-word H title, also used for The Hustler and Harper. was considered a lucky charm and branding tool for a Newman movie). In this film, he would play John Russell, who was taken and raised by Apaches as a child, then rescued by a white man, then cast out of white society when he chose to rejoin the people with whom he had grown up. At the beginning of the movie, his white father leaves him an inheritance. “This is a big something to think about,” the Mexican horse trader Mendez (played by Martin Balsam) tells his friend, a man “raised among red devils to be a red devil,” as he puts it. “You can live among white men again, speak English to people, no matter what language you think in…get your hair cut…You can be white, or Indian, or Mexican. Now, it pays you to be a white man. Put yourself on the winning side for a change.” The first moments of Hombre, when we see Newman, blue-eyed, apparently covered in bronzer, and wearing an ill-fitting black wig (which he hated and complained about) are not promising. Today, Hombre would be eviscerated for the casting of Balsam, and for its use of the trope that the only way to understand a minority population is via the experience of a non-minority interloper (an approach that dates back at least as far as 1947’s Gentlemen’s Agreement).

Hombre But Hombre is too sober, thoughtful, and self-aware to dismiss with a sneer. The majority of the plot is essentially a politically updated remake of Stagecoach (which had itself been remade to no good effect just a year earlier). Along the way, we listen to all of the passengers express their opinions, with varying degrees of racism, about Native Americans, and we watch Newman—one of them, and not; one of their targets, and not—as he listens. (Pauline Kael called this type of character “split in his loyalties…He’s a double loner—an ideally alienated, masochistic modern hero.”) The conflict is pretty quickly set up as being about ethnic identity, racism, and assimilation, not a surprise given Ritt’s and his screenwriting team’s progressive credentials. The movie is of its moment, which means that the Apaches are stoics—indigenous Poitiers who endure, with smoldering restraint, the racism of the white men who insult them. They’re not fully imagined as characters; more conscientiousness has gone into avoiding stereotypes than into writing actual roles for them. But the film is plotted very well (thanks in part to the 1961 source novel by Elmore Leonard), and written with quiet passion straight through to its downbeat ending. Newman didn’t have a great time on the shoot: a New York Times Magazine reporter who visited the set found him gnawing his nails, smoking two packs a day, punching a horse (!) that tried to bite him, complaining that scheduling problems were cutting into his vacation time, and vowing, after 22 movies in 10 years, to work less while complaining that “if I waited until I got a good script, I would work about once every three years.” The star ended his work on Hombre by barking, “All right, fellas. No sentimentality. Let’s all just clear out of here.” His taciturn-to-a-fault performance irritated some critics, as did the movie (“In Hombre, the H is silent, and so is the star,” cracked the reviewer for Time, who added, “One white man who has certainly made him suffer is Martin Ritt.”) Newman would be back in everyone’s graces later in the year with Cool Hand Luke, the success of which would overshadow Hombre. But 50 years later, the film stands as a flawed but compelling marker in the careers of a director and actor whose politics both became richer and more complex as they aged. Mark Harris is the author of Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (2008) and Five Came Back (2014).