(2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick 1968) Though he’s still never been invited to present one of his own films at the festival, Christopher Nolan became the center of attention during the first weekend of Cannes this year. On Saturday, his master class in the relatively small Buñuel Theater at the Palais very nearly caused a mob scene, with ticket and passholders scrumming with each other and arm-interlaced guards to access the theater—hundreds were unsuccessful—all for the privilege of witnessing the erudite but not especially gregarious director answer an inordinate number of questions about 2000’s Memento, of all things. Then on Sunday, he was on hand at the Salle Debussy for the event that brought him to the Croisette: the premiere presentation of a new “unrestored” 70mm print of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey—a process he both initiated and personally oversaw at Warner Bros., the distributor of his own 70mm projects Dunkirk and Interstellar. Timed to the 50th anniversary of the film’s original theatrical release, the new print was struck from the original camera negative of the earliest screening version of a film that later underwent panicky last-minute edits. Nolan was quoted in the project’s press release, which he subsequently paraphrased at both the master class and the premiere, as saying that there were “no digital tricks, remastered effects, or revisionist edits” in preparing this edition, which will receive a limited theatrical run in select, 70mm equipped theaters starting later this month. “This is the unrestored film.” That’s not exactly the standard way of selling an old film, nor is this version, with its intermittent ruptures, imperfections, and lightly weathered texture the standard way of presenting one. But in a moment of renewed interest in 70mm film, thanks to Nolan’s own ambitious large format release of Dunkirk, and auteurs such as Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino also working either directly with 70mm film or authorizing blow-ups, the time might be ripe for such an unconventional, stridently analog approach. The day after the Cannes premiere, Nolan talked to Film Comment in a quiet, well-appointed hut on the roof of the Palais, where he talked about the genius of Kubrick’s film, elaborated on the thinking behind the 2001 re-release, and advocated for filmmakers to become more involved with the theatrical presentations of their work.

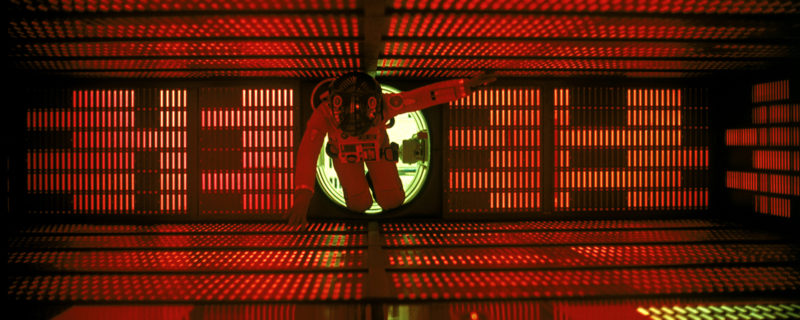

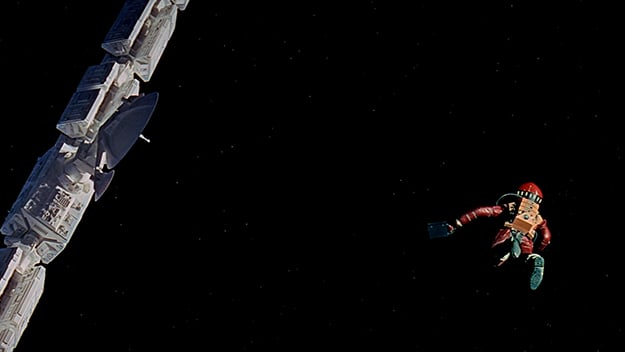

I was at the premiere last night and noticed you watching through 2001: A Space Odyssey again. Are you still discovering things in the work? I have watched it dozens of times in the last few months as part of this project, and every time I find new things, and have a new respect for the film. That’s the sign of a great masterpiece. More specifically the screening last night was just an incredible occasion. I’ve never heard a response like that from an audience in a movie theater. I was hoping for enthusiasm for this form of watching a film, in its original representation, but I was just blown away. Being there with members of the Kubrick family and Keir Dullea—it was overwhelming. Dullea being there felt significant to me, as I’ve always felt his performance is underrated. Seeing on the big screen the details of his performance, of the pacing and inflections of his line readings—he’s actually quite extraordinary. I told him that last night. Clearly the performance has always been overshadowed by the magnitude of everything else surrounding the film. I mean, it may be one of the most underrated performances in film history. And having him there look so youthful—his aging in real life has been far better than how they imagined it [in the film]. His work is layered and complex, within these extremely tight confined dialogues. I call it “bureaucratic dialogue,” in that nothing is about anything other than the exact specific technical situation they’re discussing. But the character comes through that. It’s a present tense character; there’s nothing about who he was back on Earth or how he got this job—he’s just in the moment. I was struck anew by how Kubrick creates suspense out of slowness. It’s such an incredible risk to take, because that’s just not how one typically builds suspense, with very few cuts, and waiting several minutes for a pod to turn 90 degrees while a man is flying into deep space. Last night I was thinking it felt more like a Hitchcock film than I ever realized. I’ve seen it so many times, but with an audience there you just want it to go fast, you know? And of course you immediately realize that it’s completely deliberate. That’s the whole point, that this space pod is not the world’s greatest rescue vehicle. It’s severely limited in its ability, and you wouldn’t want to get a hospital in one of those if you were in trouble. It creates such frustration—you want things to hurry up and he just stretches it out magnificently. The other thing I noticed last night was when he goes into the pod and the door closes you get this massive read on the explosive bolts sign. I had never quite clocked how specifically Hitchcockian and efficient and simple that is, in terms of you understanding what’s going to happen. The film is full of things like that. It always seems that if you’re able to read a label or sign in the movie, it’s because you’re deliberately supposed to read it. It’s never a throwaway. It tells you something simple that you then need for the rest of the film.

In your introduction last night you said that this 70mm presentation can transport us to 1968, to what someone in 1968 was able to experience with this film. Why do you think that’s valuable? As someone who cares about film history, who practically fetishizes these things, I’m very much there for it. But does it go beyond that for you? There’s something else that’s very important. Technology—actually I don’t call it technology . . . the medium of film as it existed in 1968 was vastly superior to what we have now. And you have to put up a presentation like this for people to understand, because they just don’t believe you otherwise. With analog film there’s an emotional involvement to the material, there’s a depth and there’s an openness to your relationship to the imagery and to the narrative. I mean, I can tell you with absolute certainty that if we had screened a DCP [Digital Cinema Package] last night [the presentation] would not have had that response. I know that in my bones. I know that it was about the freshness of the experience, it was about the emotional content. A lot of the information is thrown away when you digitize. In sound terms it’s overtones and subtones—things that you can’t consciously hear. An analog medium has all kinds of complicated cross-talk between the different frequencies of information that you’re getting, which have a particular character to them. We are finally waking up to the fact that our new systems are inadequate compared to the photo cameras. They do something different. [Digital] solved a lot of problems we had before with the wear and tear on prints, and it was a tremendous step forward in terms of consistency in presentation. But I call it the McDonald’s approach—and I’m a fan of McDonald’s. Everything is the same. It’s not Michelin-starred fine cuisine. You’re bringing everything down to a consistent level, but it’s well below what movies can be. And that’s what last night was about. You could see it on that particular screen, in a presentation that was tightly controlled and highly detailed, all of it from Stanley Kubrick. The lights go down, and then the overture plays, an overture that’s printed on the films. There’s black running through the projector all the time the music is playing—same thing with the interval and the play-out music after it says “The End.” There’s another seven minutes that are at a very low level, and the music carries on as people left the theater. And this is the thing that’s so important today. It’s not about fetishizing the past. I mean, we all have that component, but for me it’s about saying “Hang on, we’ve lost something for ourselves. As filmmakers we’re being asked to think of our narratives as content, which is a wretched word and one that very specifically, by calling it “content,” removes the right of the artist to be the creator, for the filmmaker to care about their presentation, to say “What size screen do I want to make this for? What’s the room going to be like? What’s the lighting?” We have to get back to the understanding that when a filmmaker makes a film, the presentation is part of their mode of expression, it’s part of the cinematic narrative that we construct. Kubrick was famously involved in the projection of his films. He’d send letters detailing how to present and project them. So I wonder if he’d appreciate DCP for its uniformity and reliability. Though what you’re describing is a level of control and intentionality that actually fosters a unique live experience, wherein the terms are uniform but the projection itself feels active and unique. The uniformed experience is distancing and unrealistic to a degree. I mean, that’s what television is. Television works in a very uniformed way because whatever the quality of the picture or the room you’d normally view it in, it’s about the content, it’s about what you hear. Like listening to the radio in different places. Cinema is not like that, cinema is more like the theater, where the architecture of the place has an influence on the experience that you have. Every presentation is going to be slightly different. Struggling to control these things is something filmmakers have always gone through, and it’s something Kubrick famously went through. The fact that that’s a struggle doesn’t mean it’s a problem that’s supposed to go away. It just means that it’s part of the creative process.

Choosing to work on the massive, wide-format scale of 2001, a scale you’ve been working on in your most recent films, how do you reconcile the fact that these works also need to be seen on smaller formats? How do you work in such fine detail, as Kubrick did with multiple, detailed live action inserts within the same frame in certain sequences, knowing that these can’t really be appreciated unless you’re watching it on a big screen? If you take Kubrick as an example, he carefully formatted his films for television. If he had shot widescreen, he would remove and authorize the 4:3 transfer, he would do mono-mixes, because that’s what at the time sounded best coming out of a television, obviating the need for interpretation by the TV stations. As filmmakers today we engage in the same process—we go back in. In fact I got involved in this process because I was in the lab transferring my films to 4K, which required projecting the films and comparing them with the digital projection. But this is where the current corporate structure ignores the reality of what the process is. When you look at a film on your phone, your brain is watching in a different way. Your brain is saying, “I know this once played in a grand cinema with thousands of people watching it,” and that affects the way you watch the screen. You bring that to it. This is what everyone is in massive denial about. Our whole lives, you turn on the television and you can tell within seconds whether you’re watching a feature film or a television program, or a soap opera or a news broadcast or a sports program. We’re very attuned to these differences. We’re all familiar with that slightly weird feeling you get every now and again, where you’ve mistaken a TV commercial for a real program, and you feel slightly embarrassed. But it rarely happens. We’re totally sensitized to the technical differences, and to how creative differences add up to this thing. The idea that the audience can’t tell the difference flies in the face of absolute reality and the way in which people have always consumed media. Actually I don’t even feel like saying consuming—it’s ridiculous, you don’t eat the picture. It’s true that those lines have gotten a little blurred over recent years, but the reason is that we’ve been degrading the theatrical experience by shooting on video cameras and sometimes not doing a very good job of it. Yes, it looks more like TV in some ways, but we’re also very sensitized to analyze film instinctively, and the audience is absolutely ruthless. It’s not that I have a disdain for digital technology at all—it has some incredible uses, but you have to understand its limitations. Look at the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park in 1993. That digital rendering doesn’t fool the eye anymore, but it did back then. I remember going to see that movie and was absolutely blown away. No longer. And the reason is we have a developing perception, a developing eye and when a trick is new it fools us. Once everybody is doing the same trick we get more used to it. Right now we’re reaching a point where—I don’t even know if I should say it really—where with 2K digital projectors you’re really seeing the difference. Whenever you put up a film print now, everyone’s seeing the difference. I felt it in the room last night. It’s profound and it’s not nostalgic, it’s a quantitative difference. I’ve done a series of events over the last few years with Tacita Dean, who is a visual artist in the UK who works with 16mm, and she’s sort of setting up these series of events to do together called “Reframing the Future of Film.” And the arguments from the art world have always been massively persuasive, and I’d like to bring them to the studio world. In the art world it’s understood—Picasso painted a painting, you can’t make a print of it, put it on a wall and tell people this is the original. Stanley Kubrick shot the film in 65mm to be printed on 70mm for this movie, photochemically. You can’t show a DCP. I mean, you can, but you have to tell people it’s a DCP, as it’s a different experience and translation of the work. If you want to see the original work, what we did last night is as close as you can get. But you could see why, considering the state of multiplex projection, and newer habits of viewing films on smaller screens, a filmmaker might say, from the outset, “I need to make films for this reality.” Instead of downshifting to that reality, you’re saying let’s upshift to meet these big screen films. Yeah, well you’ve got to challenge the exhibitors. I meet theater owners pretty regularly, and they don’t get a lot of calls from filmmakers. They like to grouse about stuff, and they don’t necessarily want to sit in a room with the theater owners and talk it through, but there’s a willingness there. We had a lot of cooperation on Dunkirk. We went out with 138 70mm presentations of the film, including IMAX, and that’s the largest 70mm release for at least 25 to 30 years. Even at the height of 70mm projections in the 1950s, I think there were only around 120 prints. There’s been this McDonald’s mentality where it’s as if everything has to be the same, but it’s never really going to be the case and it’s not the case today because the charging for 3-D, for IMAX, and every theater chain has its own sound format—this, that, or the other. So we’re actually back in a world of creative presentation where there are a lot of different ways to do these things. And I’ve always engaged in that dialogue, whether it’s with the IMAX people, or the people from AMC and Regal, to try and do the best thing, the most interesting thing possible. We were offering seven or eight versions of Dunkirk, which took a lot of time and effort, but it’s worth it to be able to go to different theaters in different ways. I think things are starting to move away from that “one size fits all” form of presentation as theaters are looking to innovate. But it has to be driven by filmmakers. That’s where they hit a brick wall because, you know, they can put bigger cup holders with reclining seats or whatever, but as far as what you want out of the experience… The theaters are being asked to innovate technically, and part of me says, “You know what? That’s our job. That’s the film, that’s what goes on the screen. You just need to have a great standard for presenting it.” Analog color on film is a medium, and I need that for my work. And selfishly, by commemorating 2001 on its 50th anniversary and re-presenting Kubrick’s work in the form it was intended to be seen—what better example is there of the power of photochemical film? There’s not really anything that hits you in the face like that.

Another thing that’s changed over time, since this call for uniformity in digital presentation, is the circumventing of the role of the projectionists, the people who actually put their hands on the prints, with 70mm projection being the most physically involving of all. With film you know somebody is up there providing this projection, it requires maintenance and oversight. We can’t take that for granted anymore. And it’s part of the live experience. It’s an essential part. Even in the digital world, projectionists are still appreciated. The bigger argument that is being thrown at me about [why we can’t show] film anymore is that we can’t find projectionists, we can’t train them. As if they were brain surgeons who took 20 years to learn. I’m like, guys I don’t remember you having that much reverence and respect for the projectionists 20 years ago. And it was just 10 years ago that we were putting up 15,000 prints—they didn’t all get sucked up in some spaceship and taken to another planet where they still show film prints. There’s plenty of projectionists and there’s plenty of young kids learning how to do it and learning really well. We did a screening of films by the Quay Brothers in New York and there were four different prints, four different aspect ratios, and two lens changes. The projectionist I believe had been working for eight or nine months, and did it perfectly. Moving, masking, changing lenses, a perfect presentation of the four films. At Alamo Drafthouse, they run projectionist workshops every year, training people up. We owe it to ourselves as a culture to watch films this way. It isn’t nostalgia—that’s like accusing galleries of indulging in nostalgia if they display paintings. It has nothing to do with nostalgia. It’s the right thing to do and the appropriate way to do it. It’s also fun, and it’s the best time you’re going to have at the movies. That’s the bottom line. Eric Hynes is a journalist and critic, and curator of film at Museum of the Moving Image in New York.