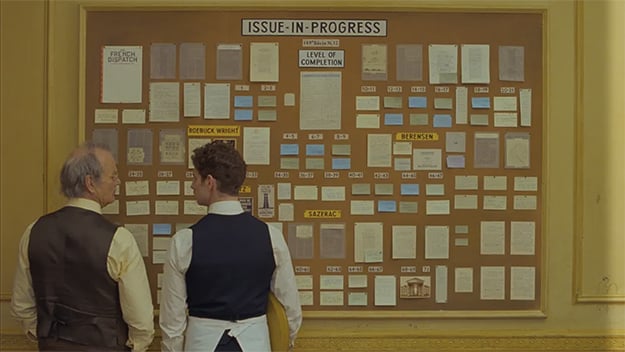

The French Dispatch (Wes Anderson, 2021) There is a point in every journey when you’ve come too far to go back, but the end is not yet in sight. For Laura (Seidi Haarla), star of Juho Kuosmanen’s lovely Cannes Competition title Compartment No. 6—a film evocative of the social awkwardness and absurdity of long-distance solo train travel—it’s when she speaks to her lover Irina from a phone booth in St. Petersburg. Irina says nothing particularly cruel, but from her distracted manner and the sounds of people’s laughter in the background, Laura understands that their relationship is ending. She can’t return to Irina in Moscow and must go on to Murmansk as planned, however boorish and sozzled her train-cabinmate may be. For veteran Cannes-goers, the equivalent moment—our very own St. Petersburg phone booth, if you will—is called “Monday.” Monday in Cannes is unusual in that it rolls round once and only once in each edition; unlike Tues-Sat, you never have to clarify which Monday you mean. Monday is also, spoiler alert, the day after Sunday, and hence it dawns as the traditionally overstuffed first weekend ends, meaning attending press wake up to a fresh backlog of work not yet done, reviews not yet filed, press agents not yet mollified. Given that this year’s Covid-mandated booking system only allows us to plan a couple of days ahead, Monday felt even more marooned in the middle than usual, with the Murmansk of the festival’s end not yet even clickable on the temperamental ticketing website. And for many, this Monday’s fugue-state was further intensified by the hangover they were nursing after bunking off to watch the final of the UEFA European Football Championships. As it happened, the result was a boon for the more patriotic Italian element who may have been smarting earlier when previous Palme d’Or-winner Nanni Moretti’s Three Floors played to a cheerfully murderous reception, quickly becoming the frontrunner for the Cannes competition’s equivalent of the wooden spoon award. If the audience at Mia Hansen-Løve’s Bergman Island, which was programmed directly against the soccer final’s second half, did seem noticeably sparser, it did not do the film’s largely rapturous reception any harm. But every attendee at Cannes needs at least one instance where they look at the consensus emerging around a particular title and wonder if everyone else was huffing glue, and this critic found it in Hansen-Løve’s vanishingly wispy, terminally self-involved doodle. The story of a filmmaking couple (Vicky Krieps and Tim Roth) on the outs on a Swedish island now turned into something of an Ingmar Bergman theme park, this work of meta-auto-auto-metafiction has layers like an onion: peel them away and you are left with no onion at all. Of course, there must also be the opposite phenomenon, whereby you find yourself championing a film that is widely disparaged, or at least shrugged off. Suddenly, it was I who was suspected of glue- (or maybe printer’s ink-) huffing, over The French Dispatch, undoubtedly among the Wes Andersoniest of Wes Anderson movies, and therefore absolutely not going to win him any new converts. Even some erstwhile enthusiasts found the anthology structure here to be a stumbling block (it comprises four short films, a prologue, and an epilogue, loosely bound into the cinematic equivalent of a New Yorker–style arts, culture, and politics periodical). But given Anderson’s tendency to paint himself into immaculately overdesigned and color-blocked corners in longer narratives, the structure of the new film actually means no one storyline sticks around long enough to get in a tangle. Instead, we get all the flabbergasting attention to detail (and here it is raised to an almost worrisome level of creative monomania) in a starry package that does not pretend to depth but delivers across the breadth of Anderson’s inimitable craftsmanship. (Of course, I may just be just dazzled by the journalist’s wet dream of an editor, played by Bill Murray, who, when an issue looks to be running long, elects to “shrink the masthead, pull some ads, buy more paper” rather than cutting a word.) [Ed. note: Nice try, Jessica.] “Style over substance!” is a critique usually levelled at Anderson, so it’s ironic that in Monday’s Competition programming Dispatch was double-featured with Petrov’’s Flu which could perhaps be accused of the same thing, but in a different, more deranged, way. A labyrinthine, gangrene-fever film shot in the brief stretch between director Kirill Serebrennikov’s release from (deeply dubious) house arrest in April 2019 and the start of the pandemic, it takes in reality, dream, memory, and fantasy, often in a single, theatrically choreographed long take wending through dystopian Yekaterinburg. Fast, ferocious, funny, impossible to follow, and rendered in images so fetid you might think about double-masking for the duration, it is the bravura work of a man acutely aware that prisons come in different sizes, and that freedom, in a diseased society, is a very limited concept. If Petrov’s Flu is about the impossibility of escape—from the past, from your roots, from your circumscribed circumstances—it’s an idea played more literally, though no less convincingly, in Director’s Fortnight title, Murina. An unusual hybrid of Patricia Highsmith–esque noir, picturesque travelogue, and coming-of-age drama, Antoneta Alamat Kusijanović’s assured debut evokes a powerful atmosphere of sunny menace on the Croatian coastline where a local teenager is tantalized by the idea of liberation from her overbearing father by the arrival of a rich stranger. It’s been one of the stronger titles in a Quinzaine lineup that has had a quiet few days except for certified breakout Hit the Road, the first feature by Panah Panahi. In mounting a road movie, Panahi was not only boldly inviting comparisons with his own father Jafar’s work but also with that of Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami. So it’s quite an achievement that Hit the Road is such a delightfully distinctive addition to and subversion of the genre, featuring a superb set of performances from an intergenerational cast. But then, at the movies, cars are never out of fashion as literal and metaphorical vehicles for revelation. With the deservedly well-received Competition film Drive My Car, director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi takes a leaf from the Burning book of Lee Chang-dong, and adapts a 40-page Haruki Murakami story into a three-hour film that is not padded but beautifully modulated. A meditation on grief, fidelity, and that other Murakami staple, the unknowability of the human heart, the filmunfolds with barely perceptible gear changes as a theater actor/director (Hidetoshi Nishijima) in mourning and his driver (Toko Miura) open up to each other in the strange intimacy of a daily car ride. Vehicular intimacy and fatherly grief of an extraordinarily different and far more pungent variety mark out Julia Ducournau’s Titane, which played late on Tuesday night. Several days and therefore lifetimes ago, we were a press corps divided by Paul Verhoeven’s trashy, lascivious reimagining of the story of Benedetta (Virginie Efira), a 17th-century Italian nun who was the subject of the Catholic church’s only ever trial for lesbianism. Once that polarizing debate had been and gone (I’m strongly pro, but mileage varies depending on whether it’s taken as a film from the director of Elle or the man behind Showgirls), it seemed we had entered a more sedate phase, until Ms. Ducournau—promoted to Competition after her 2016 Critics’ Week breakout Raw—petrol-bombed the Debussy into stunned submission last night. Titane is a wild, wild ride, in which Ducournau, via fearlessly embodied newcomer Agathe Rouselle and ferociously against-type veteran Vincent Lindon, investigates queerness, dysmorphia, body modification, and the efficacy of the Macarena as a CPR teaching aid, in images acrid with neon and diesel. It’s a startling marker of the end of the middle of Cannes, belching up a column of smoke from its raging tire fire that will undoubtedly still be visible in the rearview by the time we get to the promised land, aka Murmansk, or, as we call it around here, Saturday. Jessica Kiang is a freelance film critic with regular bylines at Variety, The Playlist, The New York Times, Rolling Stone,and Sight & Sound.